Verizon’s Refusal To Repair Landline Service Leaves Elderly Man Without Phone For Months Image courtesy of (Alain Ferraro)

While plenty of Americans rush to acquire the latest and greatest in new telecom technology, there are some that only need the basic phone service they’ve had for decades. But as we’ve seen on multiple occasions recently, a number of traditional landline users are being left out in the cold as Verizon tries to transition customers away from copper line service and to fiberoptic phone lines. And for one elderly New Yorker, Verizon’s apparent inflexibility resulted in months of having absolutely no service at all.

It’s no secret that Verizon wants out of the copper-wire landline phone business. Copper is expensive, fiddly to maintain, and highly limited in how much data it can carry in a bandwidth-hungry era.

Consumer advocates and Verizon’s own workers have accused the company of deliberately neglecting copper lines in an effort to push customers to fiber, and the FCC recently fined the telecom titan $2 million for failing to investigate complaints about rural phone service, which is still largely copper.

Meanwhile, some customers who depend on their landlines are having their maintenance and repairs ignored to the point where upgrades are the only way Verizon will maintain their service.

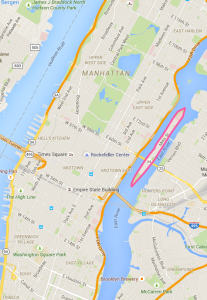

That’s what happened to a Consumerist reader’s family over the past two years.Roosevelt Island is exactly what the name suggests: a small island in the East River between Manhattan and Queens, running parallel from roughly E 47th St to E 85th.

The geography of it is important: although Roosevelt Island is nominally a New York City neighborhood like any of a hundred others, when it comes to infrastructure, it shares the challenges of any other small island: when the cables that run to it are cut, service is gone. There are no easy work-arounds, and repairs take time.

That’s where reader “T.”‘s father lives. Her dad is in his late 70s, with some health issues, and lives alone. Phone service is vital to him, for reaching his doctors, his adult children, and 9-1-1 if necessary.

And yet on two occasions — totaling up to three solid months over the course of a year-and-a-half — Verizon, left him hanging high and dry.

The Saga

Image courtesy of Alan BruceAfter 25 years of stable phone service through Verizon (and its predecessor businesses), T’s father had two huge outages in the last two years that eventually led to the family canceling their service.

The First Round: 2013-2014

November 7, 2013: During a construction project, a number of cables providing telephone and cable service to Roosevelt Island residents are accidentally sliced through.

Within 24 hours, service to Time Warner Cable customers and to Verizon FiOS customers is restored. However, outages persist for traditional Verizon phone subscribers.

November 10: Several days after the incident, roughly 900 Roosevelt Island residents are still waiting for Verizon to fix their copper-wire landline service.

November 11: T asks staff of her father’s apartment building when phone service will be restored, noting a sign in the lobby confirming that the problem affects the entire building. She is told it will be another week or two.

November 12: Verizon confirms that four cable bundles — two fiber and two copper — providing service to a total 1300 customers were cut in the accident. Of those 1300 connections, about 400 were fiber that was easily restored within a few days. Service to the remaining 900 copper-wire customers, a spokesperson says, will continue to be restored “over the next couple of days.” Verizon provides a “wireless on wheels” trailer with wifi, phones, and iPads that customers may drop by and use during business hours.

December 11: After a month without updates, T starts asking around. Building staff are surprised to hear that her father’s connection is still out, as some customers in the building are apparently already “back up and running.”

T speaks with Verizon customer service, which credits her father’s account for the entire month of November. They tell her they expect service to be restored by December 23.

After providing her contact information to Verizon, T receives a text message confirming that a service ticket has been created and a service appointment is set for December 23, between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m. “I didn’t recall making a repair appointment,” T said, “but since my father would be home that day, if they needed to send someone over to get him back up, that would be fine.”

December 23: The tech shows up on time, but he’s not there to fix the copper — he’s there to say that Verizon can’t repair the copper lines, and the service will have to be upgraded to fiber. T’s father refuses; the tech says that someone will have to call Verizon to schedule a new repair appointment and leaves.

December 28: A Verizon representative leaves a voicemail for T; she calls back. During their conversation, the Verizon rep says the same thing the tech did: that the copper service can’t be repaired, and T’s father will have to be upgraded to fiber to continue receiving service.

This sounds questionable to T, who is pretty sure that other customers have had their old service restored. T tells the Verizon rep that she is going to check with her father’s building to see if all the other customers had to be switched over to fiber, too.

T then calls Verizon’s customer service again and speaks with another representative. The second rep says that there is an “external outage” in the area, that 13 customers in T’s father’s building are still without service, and that no repair tech will need to be sent to the apartment to restore service. The second rep confirms that the outage will absolutely be fixed by January 7 at 7 p.m.

T starts asking around on Twitter and hears that at least one other Roosevelt Island customer had their landline service fixed within a week of the outage, without being swapped to fiber.

January 7, 2014: Still no service. T calls Verizon once again and receives an automated recording saying that service will be restored “no later than January 18 at 7 p.m.”

T speaks with a representative who confirms the new deadline for repair is January 18 and that T’s father is one of 10 customers in the building still without service. T asked to know why different Verizon employees kept telling her different things, and if her elderly father’s repair could be expedited.

The rep told T he would put a note on her father’s account noting that her father is elderly, and that someone would call her the next day to update her on the status.

Frustrated, T blogs about the experience and starts e-mailing Verizon’s corporate communications team.

January 8: A representative from Verizon calls T to tell her that there is a repair tech on the island to fix her father’s service as they speak. T also notes that the rep called her by the nickname she blogs under, not the full legal name she has been using with them so far.

Four hours later, T’s father’s phone service is finally restored. He has not been upgraded to fiber; somehow Verizon managed to fix the copper-wire service after all — and ahead of their frequently-revised estimate.

T revises her blog post to include the update, and two full months after the service outage began, her father can once again finally call his family and his doctors. Hallelujah!

Round 2: 2015

July 8, 2015: Roosevelt Island residents can’t catch a break. A second, different construction project in the area also doesn’t watch where they’re digging, and cuts phone cables to Roosevelt Island. Again.

The outage is widespread, affecting residents, businesses, and public safety organizations in Roosevelt Island. Verizon tells customers, including T, that they will have the outage resolved by July 21.

July 14: T receives a voicemail from Verizon saying that a FiOS tech had tried to come by to restore service at her father’s apartment, but that nobody was home.

There’s just one big problem: Neither T nor her father had ever scheduled a FiOS service appointment. He still did not want fiber phone service (finding it more expensive and also less reliable, especially during a power outage), and there was no reason for FiOS to think there was a scheduled tech appointment for T and her father to miss.

T called Verizon to find out what was going on. A representative told her that according to the information he had available, the copper-wire service could no longer be repaired, and the only possible way to restore her dad’s service was to switch to fiber.

T asked the rep point-blank if Verizon had cut off her father’s service in order to force him to switch. She writes, “suddenly he sounded nervous.” She says the customer service rep told her: “We haven’t cut it off, we have to run a line test to assist. Let me look more closely at the notes on the account… There was an outage, the outage was restored, let me see what my line test says… Current issue that I’m getting is a voltage issue, which is a network issue, so I can put the ticket in here so they can work to restore that but there is a notation here that again there is a request to resolve the issue permanently by going to fiber optic.”

T reiterated to Verizon that her father was not interested in fiber; the rep responded with “a long spiel” about copper wire being too old and prone to failure. After arguing the matter back and forth, T pressed for a deadline by which she could see her father’s service restored; the rep told her that if they were able to resolve the issue, service should be restored by 7 p.m. tomorrow, July 15. If not, they would contact her to set up an appointment for a tech to come to the apartment.

July 15: Service is not restored, and Verizon does not call.

July 17: T goes up the ladder at Verizon, once again e-mailing corporate communications and threatening to take her father’s story to local media. Within a few hours, she had a response from Verizon’s corporate office in Brooklyn.

T reports that the Verizon representative told her, “that the bottom line is that the copper will not be restored. They refuse to do it, they’re trying to convert everyone to fiber because it’s more reliable, etc. The copper is kaput.”

The rep told T that he could send someone over tomorrow to install fiber and get her father’s phone reconnected. T responded that she was very upset with how Verizon had been handling the situation, and that if Verizon was refusing to reconnect her father’s traditional landline service, that she and he would rather switch to VoIP through Time Warner Cable since he already has television service through them anyway. The Verizon employee told T he understood.

July 20: The next business day (7/17 was a Friday), T receives another voicemail from Verizon explaining that the scheduled FiOS technician arrived for an appointment, but was unable to get in.

Neither T nor her father scheduled any technician. The phone service remains out. T has had enough of dealing with Verizon and files a complaint with New York’s Public Utilities Commission.

July 21: The PUC responds, telling T:

The PUC also gives T a case number for her complaint, and advises her to call them back if Verizon has not handled the matter to her satisfaction within two weeks.

July 22: T receives five separate calls from various Verizon representatives “all falling over themselves to explain to me why Dad had to switch to fiber.” T called one of them back to explain that her father would be switching carriers.

T had to specifically ask Verizon to stop sending unwanted technicians to her father’s apartment. The Verizon employee she spoke with said, “The reason they keep coming is because there’s a ticket in saying the only fix is to upgrade him to fiber.” T asked to have that notation removed from her father’s account so technicians would stop showing up at the door.

July 27: The number for T’s father’s phone is successfully ported over to Time Warner Cable and the family cancels their Verizon service.

The Bigger Picture

Image courtesy of jpghouseT and her dad are far from alone. It’s no secret that Verizon wants out of the copper wire business as soon as possible. They’ve been trying to convert customers to fiber for years, especially in the metro New York area.

Verizon has been asking their landline customers to upgrade since at least 2012. In recent months they’ve gotten downright pushy, telling customers from New Jersey to Virginia that they need to let Verizon upgrade them from copper to fiber ASAP or lose service altogether.

The company has also frequently chosen not to replace copper wire destroyed in disasters, as in the miles of wiring wrecked during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Customers in New York and New Jersey saw their service replaced with a wireless option first, which didn’t work very well and ended up replaced again with fiber optic cables.

Verizon’s tactics have not gone unnoticed; the company has repeatedly faced accusations that they intentionally let their copper-wire networks go to rot. In 2014, a consumer advocacy group in California petitioned that state’s Public Utility Commission to investigate Verizon’s practices. The group claimed that Verizon was “deliberately neglecting the repair and maintenance of its copper network with the explicit goal of migrating basic telephone service customers who experience service problems,” and asked the commission to “order Verizon to repair the service of copper-based landline telephone customers who have requested repair or wish to retain the copper services they were cut off of.”

This year, that accusation was echoed by a union representing 35,000 Verizon employees. In June, the Communications Workers of America filed Freedom of Information Act requests with utility regulators in six mid-Atlantic and northeast states and D.C., claiming that the data would show that Verizon fails to meet their obligations for network maintenance and repair. At the time, the CWA said that, “the company abandons users, particularly on legacy networks, and customers across the country have noticed their service quality is plummeting.”

Verizon responded at the time that the union’s allegations were “pure nonsense,” but the company is clearly unabashedly interested in retiring copper as quickly as they can.

We asked Verizon about T’s dad’s line, and they confirmed that it suffered repeated problems affecting service. However, a representative told Consumerist, Verizon no longer considers repairing that line, which they confirmed doing in the past, as “the best solution for our customers.”

The representative continued, “We want to make sure they have reliable and consistent service, and the best way to provide that is over fiber optics, a 2015 technology vs. copper, a 1930’s technology.”

Verizon stressed repeatedly to Consumerist that the fiber upgrades they are pressuring T’s father and other landline customers to take are not the same as signing up for FiOS service, nor is the change directly related to the broader IP transition.

“All the services that are provided over copper-fed telephone service are available and provided over fiber as well. … It is simply using a different method for simple telephone service,” Verizon told Consumerist. “We are not asking people to move to FiOS and subscribe to all (TV, Internet, enhanced phone) those services. … Telephone service over fiber goes though the same network as copper-fed service. … It has nothing to do with the Internet. FiOS Voice (the enhanced telephone service offered as part of the FiOS package of services) is IP. But simple telephone service over fiber is not.”

That, however, is not the message that was conveyed to T and her father.

Several of the messages left for T specifically referenced FiOS service technicians, as did some of the customer service representatives she spoke with. They also referenced installing an optical network terminal in her father’s apartment — a signal encoding/decoding device that Verizon’s support site explains as being part of FiOS service.

There is an irony in Verizon is pushing their fiber service on customers like T’s dad, who don’t want it, even while tens of thousands of other New Yorkers are still waiting for their long-promised Verizon fiber to arrive.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.