Today In Terrible Arguments Against Net Neutrality: Monopoly Eras And Fees On Bills Image courtesy of (Photo: Consumerist)

It’s been a busy day for tech talk in Washington. Today, both the House and the Senate held hearings on net neutrality and a proposed bill to regulate it. A parade of former regulators, lobbyists, business representatives, lawyers, and consumer advocates sat on Capitol Hill and once again hashed through the debate, while elsewhere in the District, a current FCC commissioner was giving a lunchtime speech about why the FCC shouldn’t regulate at all.

It’s been a busy day for tech talk in Washington. Today, both the House and the Senate held hearings on net neutrality and a proposed bill to regulate it. A parade of former regulators, lobbyists, business representatives, lawyers, and consumer advocates sat on Capitol Hill and once again hashed through the debate, while elsewhere in the District, a current FCC commissioner was giving a lunchtime speech about why the FCC shouldn’t regulate at all.

The three events broke down into the same general sides we’ve been used to for the last year: those who wish to see the FCC regulate broadband carriers as Title II communications services, and those who want the FCC to leave the poor put-upon broadband industry alone so it can keep making money hand over fist. But today the anti-Title II side used two main arguments that just don’t add up.

In remarks he gave at the American Enterprise Institute (PDF), FCC commissioner Michael O’Rielly focused not on the business side of things, but on the consumer. The poor consumer, he said, will have to pay more for broadband if Title II happens because of something that almost nobody’s been focusing on: the Universal Service Fund.

Services defined statutorily as telecommunications carriers are required to pay into the FCC’s Universal Service Fund, it is true. The USF is where money for programs to expand connectivity to underserved populations — like the e-rate program that brings internet access to schools and libraries, or programs that expand broadband access in rural areas — comes from.

“If the commission decides to reclassify broadband as a telecommunications service, broadband providers (as telecommunications carriers) will be required by statute to pay into the Fund,” O’Rielly said. “And providers will undoubtedly pass those fees on to consumers just as telecommunications providers do today. That means consumer broadband rates will go up” (emphasis his).

But O’Rielly’s observation, while accurate, really only tells half the story.

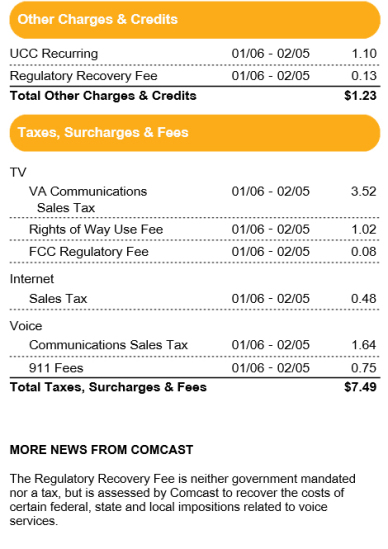

This is the fees, surcharges, and taxes section of a current (January, 2015) Comcast bill for one of our very own Consumerist staffers.

This is the fees, surcharges, and taxes section of a current (January, 2015) Comcast bill for one of our very own Consumerist staffers.

It’s showing all of the fees and charges Comcast, one of the nation’s biggest ISPs, charges a triple-play customer. Some of these vary by state, obviously. But note the “UCC recurring” and “regulatory recovery fee” charges.

The “UCC recurring” charge is the fee Comcast levies to recoup its mandatory contributions to the USF. So that one, as O’Rielly has it, is a direct pass-through to consumers.

The “regulatory recovery fee,” however, is entirely of Comcast’s own invention. It is, as they note down below, “neither government mandated nor a tax, but is assessed by Comcast to recover the costs of certain federal, state, and local impositions related to voice services.”

Note that it does not in fact appear under “voice,” but under “other charges.” In fact, a bill from a year earlier — when the account in question was a double-play package and not triple-play, with no phone or voice service associated with it — still includes both the UCC Recurring charge and the regulatory recovery fee on it.

In other words: ISPs like Comcast are already charging consumers whatever pass-through fees they darn well want, whether or not they actually relate in any way to the current services a subscriber is connected to, and regardless of the regulatory scheme that applies to those.

To adopt a stance of, “oh no, what about the poor consumers’ bills, won’t anyone think of the poor consumers’ bills” as it relates to approximately a dollar’s worth of already imposed fees that might magically manifest or increase at some point in the future, when cable and internet bills are already both increasing at many times the rate of inflation is not an honest position.

And why do consumers’ bills keep jumping in leaps and bounds? Basically, because they can. In a landscape without real competition, businesses have no compulsion to operate in consumers’ interest and instead, act only in their own. And that means charging more money whenever they want, for whatever they want, because the market will bear it.

And that brings us to the other argument lawmakers kept repeating about Title II today, in both the House and Senate hearings: that because Title II was developed in years past, to deal with a monopoly telephone system, it does not apply to the landscape we have today.

Senator Thune, in his opening remarks (PDF), said “We have now reached an unfortunate point where both the President and the chairman of the FCC feel compelled to move forward using a tool box built 80 years ago to regulate a literal monopoly,” and in Congress’s other chamber Rep. Upton said (PDF) the similar, “Our thoughtful solution provides a path forward that doesn’t involve the endless threat of litigation or the baggage of laws created for monopoly era telephone service.”

This was the recurring theme, from senators, representatives, and witnesses giving testimony: Title II was developed for a world with a phone monopoly. Since we do not currently have a broadband monopoly, monopoly rules are overbearing and harmful.

Except, of course, that when it comes to broadband, most of us are subject to a local monopoly. Whether or not you have any options basically depends on which city block you happen to live in, if you’re an urban customer. If you’re a rural customer, good luck getting any service at all. And report after report has shown that for actual high speed connections, the idea of competition remains entirely mythical for tens of millions of Americans.

For download speeds of 25 Mbps or higher — which the FCC is likely to approve as the new baseline minimum for “broadband” later this month — only 37% of Americans have a choice of even two providers to ping-pong between (a duopoly), and only 9% of us can choose from three or more players.

So for witnesses like Michael Powell to say that Title II is only “for a monopoly era” is wrong in two ways. Not only does the FCC’s ability to use forbearance mean that Title II is actually reasonably flexible… but also, sad to say, this is indeed still a monopoly era for the vast majority of consumers.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.