Study Claims That There’s A Decent Chance You Look Like Your Name Image courtesy of quinn.anya

Have you ever met someone and immediately thought “You look like a Heather,” and then it turns out they person is actually named Heather? While you might want to believe you have some kind of psychic ability, you probably don’t. Instead, a new study finds that under the right circumstances people can often correctly match names to faces based on social perceptions.

The research, published this week in the American Psychological Association’s Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, found that social perceptions can likely influence facial experience.

The study, based on eight experiments involving hundreds of people in France and Israel, explored whether or not name stereotypes can be manifested into facial appearance, creating a face-name matching effect.

“Both age and ethnicity play a role in our name and in our look,” the report states. “Our goal was to see whether the face-name matching effect could be demonstrated beyond these variables.”

Through this effect, a stranger is able to accurately match a person’s name his or her face.

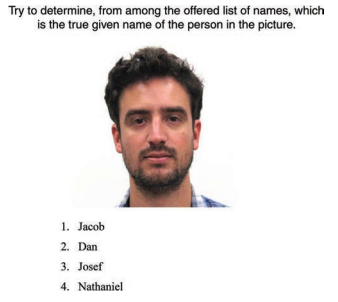

In each experiment, participants were shown a photograph and asked to select the given name that corresponded to the face from a list of four or five names.

According to the research, the participants were able to match the name to the face 25% to 40% more accurately using a list of names rather than random chance, which had a 20% to 25% accuracy rating.

The researchers believe this result may be the effect of cultural stereotypes associated with names.

For example, in one experiment, the participants were given a mix of French and Israeli faces and names. The French students were better than random chance at matching the French names and faces, while the Israeli students were better at matching only Hebrew names and Israeli faces.

The researchers also wanted to know if face-name match could be replicated by a non-human. To do this, the researchers conducted two experiments with computers that were trained with a learning algorithm.

“If a face-name matching effect emanates from a person’s face, a computer should be able to learn it and make similar matches,” the researchers hypothesized. “This procedure also allowed us to significantly increase the number of stimuli, thus strengthening the validity of our behavioral studies.”

In another experiment, the researchers asked a computer to match 94,000 faces to names. The names were presented to the computer on a two-name to one face basis. In the end, the computer was able to correctly match the names and faces with a 54% to 64% accuracy.

“These results validate our theory that a match in the stimuli itself drives the face-name matching effects observed, and not any other possible behavioral bias of human participants,” the study states.

The improved accuracy of both the participants and the computer could be the result of people subconsciously altering their appearance to conform to cultural norms associated with their names, lead researcher Yonat Zwebner said in a statement.

“We are familiar with such a process from other stereotypes, like ethnicity and gender where sometimes the stereotypical expectations of others affect who we become,” said Zwebner.

Additionally, he notes that prior research has shown there are cultural stereotypes attached to names, including how someone should look.

“For instance, people are more likely to imagine a person named Bob to have a rounder face than a person named Tim,” he says. “We believe these stereotypes can, over time, affect people’s facial appearance.”

Of course, the report notes that other factors can create shared face-name schemes, such as the literal meaning of a name or an association with a famous person.

“Converging evidence suggests that both faces and names separately convey social signals, eventually leading to a possible correlation between the two,” the report states. “Specifically, faces communicate information to the perceiver about a person’s identity.”

The report concludes that the association between faces and social perceptions could be a two-way street.

“The face-name match implies that people ‘live up to their given name’ in their physical identity,” the report states. “The possibility that our name can influence our look, even to a small extent, is intriguing, suggesting the important role of social structuring in general and naming in particular in the complex interaction between the self and society.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.