When It Comes To Food, “Generally Recognized As Safe” May Not Mean What It Sounds Like Image courtesy of MeneerDijk

Here in the U.S., we have food safety regulations — a lot of them. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for making sure foods (and a bunch of other stuff) adhere to some basic health and safety rules to reduce the likelihood these products will hit store shelves and make a million people sick. So far, so good… but there’s a major food safety system that the FDA uses that, it turns out, is neither standard nor safe — despite its name.

So, what’s this standard?

Generally Recognized As Safe, or GRAS.

And that means…

GRAS is a standard for certain substances added to food. The FDA, which regulates food safety, maintains a database of some of the GRAS ingredients that are, well, generally considered safe to use in your food.

Anything on the list is fair game for its stated use in food, without requiring a specific pre-market review process.

That sounds fine! Is there some kind of catch?

A big one.

In fact, manufacturers can determine whether something is GRAS in secret, without telling the government. That means it is actually something of a loophole.

Huh. Okay, so, how does it work?

To get there, we need to backtrack a bit: to 1958, specifically.

A quick history of food safety regulation: The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 is basically where the FDA came from. Twenty years later, in 1958, the law was updated with the Food Additives Amendment.

That’s about the point where Congress realized that it’s really quite bad for consumers if new ingredients in their food are toxic. (Who knew?!) So the 1958 update gave the FDA a way to mandate pre-market safety testing and keep harmful chemicals, including carcinogens, out of food.

That’s when GRAS came about. It’s basically a way of determining if something can be generally recognized as safe for consumption, and substances meeting that standard are excluded from the review process.

Oh, okay. So the FDA does scientific testing on potential GRAS items?

Ah. No. Not even a little.

If a food company volunteers its research for review, the FDA will look over the information that the company provides.

But the FDA still fully evaluates those findings though, right?

Well, it did. For a while, anyway.

One process for getting your item classified as GRAS was to generate and gather your evidence, then present it in a petition to the FDA. The FDA would then review your petition and issue a rule.

That rule would basically either say, “Great, your science looks good, we’ll call this ingredient safe,” or something like, “We deny that the science was enough to declare the ingredient safe,” and your ingredient would get the green light (or not).

When did that change?

The FDA proposed a rule change in 1997 that would, “eliminate the GRAS affirmation petition process and replace it with a notification procedure.”

In other words, it would take out that make-a-rule step. Instead of the FDA having to review the findings and give them a thumbs-up, companies would simply notify the FDA that they had tested a thing, found it safe, and would now be using it.

That is, if they want to. The notification part is simply not mandatory.

The FDA basically says “you only have to tell us if you want to?”

Yep.

When did it go into effect?

The final version of the rule went into the Federal Register as officially-official on Aug. 17, 2016. Yes, 19 years after it was first proposed. And yes, that is slow, even for a large federal bureaucracy.

The rule was only finalized at all as the result of a 2014 lawsuit from the Center for Food Safety. It, and other consumer safety watchdog groups (including the policy and mobilization branch of our parent company, Consumer Reports) argued that the proposed GRAS process violated the actual 1958 law that established the GRAS standard to begin with.

The lawsuit aimed to force the FDA into finalizing a rule; however, the rule that got finalized incorporated virtually none of the changes or suggestions that advocates had proposed.

So companies can stop notifying the FDA about their stuff now?

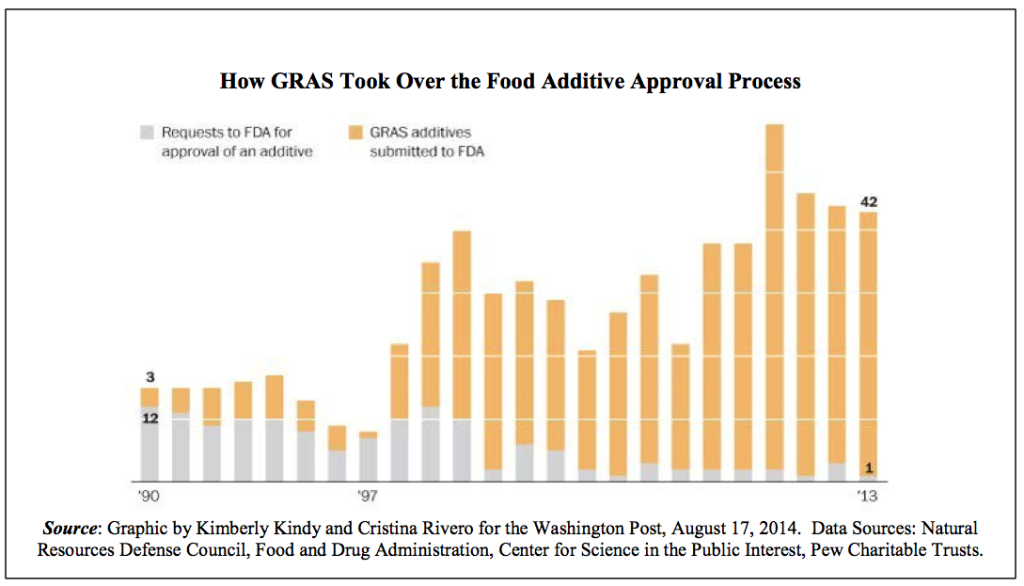

The Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) released a fact sheet [PDF] last year outlining the scope of the problem. It included this graph, showing how pre-market food additive petition approvals have been replaced with GRAS notifications over time:

What kind of scale are we talking about?

CSPI estimates that there are about 1,000 food substances being used that the FDA has never even been notified about.

So what problems does this cause?

There are two biggies.

One: Nobody actually knows what all the substances in your food actually are, nor has a way to develop a common understanding of their safety. They aren’t always labeled, either; if they’re used in small enough quantities as a flavoring, they won’t even show up as an ingredient on the package except under a broad header like “natural and artificial flavoring.”

Two: When something is already glossed over and never looked at again, but turns out to be dangerous, it can be really hard to make the case that it should be re-examined, or even to identify which ingredient is the harmful one. And, due to the secret GRAS process, we don’t even know why the company thought those ingredients were safe in the first place.

What’s a good example of that?

The most commonly-given example of a problem with a GRAS-approved substance is caffeine.

When it made the GRAS list, the rule only applied to the relatively small amounts of caffeine consumed in “cola-type” drinks only. Other than maybe giving yourself a night of insomnia, intentionally or not, you weren’t looking at any seriously deleterious effects from the quantity of the ingredient you could actually ingest.

But by the 21st century, tech and trends in food had processing changed. So, for example, there was a caffeinated alcoholic beverage that was deemed unsafe (after being linked to a teenager’s death) and was removed from the market.

But if people were dropping dead from 1,000 substances in food we’d notice, right?

That’s basically the industry response: that clearly ingredients they put in food are safe because there’s no proof of harm. And yes, if your morning breakfast cereal were to turn out toxic, it’s a pretty good bet that would make headlines.

But consumer advocates (much like Congress was, in 1958) aren’t just concerned about immediate, acute problems like fatal caffeine overdoses; they’re concerned that with unknown items in the food supply, it’s hard to identify any chronic issues they may cause.

The easiest example here is partially hydrogenated oils: trans fats. You may remember that trans fats became a big bugaboo a few years back. During the ’00s, they had to be broken out on nutrition labels, and slowly started vanishing from food.

For years, those substances had been considered GRAS. The FDA reviewed the science, did more science, and then, in 2015, pulled the designation and removed them from the list. As it turns out, things that cause heart disease and don’t really add anything you can’t get in your food otherwise are a bad idea.

But in order to make a measurement and a determination like that, first you have to know what it is you’re measuring.

If something that has been added to food causes some kind of slow-motion chronic illness or effect, how would the medical and scientific establishment even begin to chase it down and make that connection?

Basically, it’s a problem of unknowns: without independent research and disclosure, and without knowing how and when companies are making the determination that something is safe, how can regulators know what to investigate? How can consumers make informed choices about what to buy and eat?

So, basically the FDA isn’t regulating many new food substances in any meaningful way?

That’s the long and the short of it, yup.

I’m not even sure what to say.

We know that feeling. Here, try this gif:

You’re far from alone if you think this whole thing is misleading as heck. Our colleagues at Consumer Reports surveyed Americans this year and found that overwhelmingly, folks think GRAS means something it doesn’t.

A whopping 77% of respondents thought “GRAS” means the FDA has actually evaluated something and found it safe, and that another 66% thought that the FDA monitors the safety and usage of GRAS ingredients.

Neither statement as CR points out, is true.

Note: this article has been updated to more accurately reflect the GRAS process and to clarify some items.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.