Anyone Can Make & Market A Dietary Supplement, Including Consumer Reports

When you see ads for dietary supplements, there are often scientists in lab coats looking at beakers and flasks, saying science-y things. In the real world, just about anyone with a credit card can make and market a supplement, even one that contains potentially unhealthy ingredients. Just ask our colleagues at Consumer Reports, the creators of the new (totally fake) weight-loss supplement Thinitol.

As part of its new cover story on supplements, CR decided to try its hand at creating a product of its own: Thinitol.

The genesis of Thinitol goes back to 2015, when the New York Attorney General’s office alleged that many supplements sold in stores didn’t appear to contain much, if any, of the ingredients advertised on the label.

“I started thinking about what is in these supplements? Who is making sure that what’s in the supplement is in there and making sure it’s made correctly?” explains Lauren Cooper, Consumer Reports’ Investigative Content Editor. “It turns out that the FDA really doesn’t inspect very many of the facilities that make supplements, and I started thinking, well, can’t we just make one and put it on the market?”

If CR could show that anyone can just order the ingredients and materials needed to make a supplement, it might help people understand that while supplements can look similar to drugs, they’re not regulated the same way.

Regulated Like Food

A 2015 Consumer Reports survey found that nearly half of Americans believe that supplement manufacturers test their products for efficacy, and the majority said they believe that supplement makers must prove their products are safe before selling them to consumers. In reality, manufacturers can test for efficacy and safety, but they don’t have to.

“People think that these supplements have been vetted,” says Ellen Kunes, who heads up CR’s Health & Food content team.

While real drugs — prescription or over-the-counter — must demonstrate levels of safety and effectiveness before hitting store shelves, dietary supplements are effectively regulated like food products.

In a sense, says Kunes, it’s like going to a farmer’s market and buying a homemade “spice mix” containing a bunch of dried leaves, seeds, and stems. Regardless of whether or not it does the job, you’re not really sure what you’re getting.

So when it came time to pick the ingredients for Thinitol, CR selected a number of items commonly found in weight-loss supplements, including some that made the magazine’s list of ingredients you should avoid, including green tea extract and kava.

It’s possible that chowing down on all the ingredients in Thinitol might result in weight loss — the mix is effectively a cocktail of caffeine, diuretics, and a possible appetite suppressant — but that doesn’t mean the supplement is a safe way to lose weight.

“We wanted to show that something that’s kind of not safe — and certainly potentially not effective — can be put out there,” Kunes tells Consumerist, adding that Thinitol will not be released, and was just an experiment to point out how simple it is to make something that could be sold. “We are simply demonstrating the ease with which anyone sitting at home could order stuff like this and sell it on a website.”

Just A Few Mouse Clicks Away

The Thinitol team quickly found out that all the items you need to make and package the supplements are available online from Amazon and eBay. Anyone can easily order the ingredients, the bottles, the empty gelatin capsules, a simple machine that allows you to fill dozens of capsules at a time, and the bands for heat-sealing around the lid.

To acquire everything it needed to start making Thinitol, CR paid a grand total of $191.

“When I ordered all the ingredients I was pretty surprised how easy it was to get all of this stuff,” says Cooper, who was most taken aback after using the capsule-filling machine to make her first batch. “They looked absolutely perfectly real. If you were to pour them out of a bottle that you bought at the drugstore, you would never know the difference.”

Make Supplements At Your Desk

The FDA’s Good Manufacturing Practices set out the standards under which supplements are to be properly made, and they definitely do not include hand-making Thinitol capsules at your desk in the Consumer Reports office. Many reputable supplement companies follow these guidelines, but the FDA has admitted it can’t possibly regularly police all the nation’s supplement makers, especially when some elect to not register their products with the FDA.

“It’s like a needle in a haystack,” Kunes says of the FDA’s efforts to track all of the known supplement manufacturers. “They’re trying to check up on all of these different companies who are producing supplement to see that they’re producing them the way they’re supposed to be produced.”

Even some companies with apparently strict manufacturing controls have been tied to contaminated products, notes Kunes, pointing to the 2014 death of a newborn baby in Connecticut. Hospital staff had treated him with a probiotic from a well-regarded firm, but he died within days after a rare fungus overtook his intestines. Samples from the same probiotic held at the hospital turned up this same fungus, and batches of the product were recalled, though the maker says that an investigation turned up no evidence of contamination in the supply chain for this product.

Labeling With Smoke & Mirrors

“The one thing that is regulated is the way you can label supplements,” explains Kunes.

For one thing, you can’t make unproven claims about the efficacy of your product. Supplement makers have recently been caught by the Federal Trade Commission making baseless claims about weight loss, and their effectiveness in treating opiate withdrawal. Last year, the Federal Trade Commission brought lawsuits against more than 100 supplement companies for making a variety of misleading claims.

“You have to be very careful not to say, ‘We’re going make you lose five pounds!’ on the label,” says Kunes. “If you’re a supplements manufacturer, there are a lot of smoke and mirrors about the way that you can make promises.”

Adds Cooper, “If the supplements really treated heart disease, or lowered cholesterol, they would actually be considered a pharmaceutical drug and would be regulated entirely differently. In order to be a dietary supplement it’s not allowed to make those claims.”

So when it came time to make the Thinitol label, CR didn’t make any guarantee about the pounds you’d shed. The label chooses to let the generic phrases “Supports Metabolism” and “Boosts Energy” do the talking; it’s a wink-wink to shoppers that these pills will cause you to lose weight, without having to explicitly say so.

“It doesn’t take a genius to figure out, ‘Thinitol… it’s going to boost my metabolism and I’ll lose weight,” says Kunes.

“If you see a qualifying word like ‘boosts,’ ‘supports,’ ‘aids,’ or ‘helps,’ those are red flags that the ingredients in the supplements probably haven’t been shown to be effective in any medical studies,” notes Cooper.

Then there’s the “All Natural” burst, which gives the false implication that because something is natural it’s therefore safe.

Another trick of the supplement trade is the “proprietary blend,” which again treats supplements like a food product.

That store-brand acetaminophen in your desk drawer will tell you exactly how many milligrams of the drug are in each pill. On the back of your Sucrets cough drops tin, the label will spell out the amount of each active ingredient found in a lozenge.

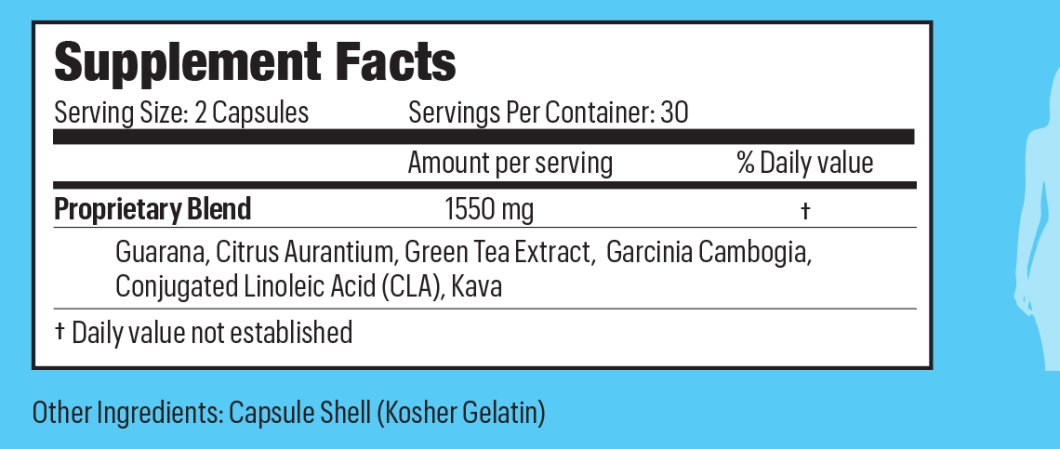

Yet here’s what the label looks like for Thinitol — and countless other supplements that are only required to list the ingredients in order of relative amount used:

So you know that the total amount of stuff is 1550mg and Guarana is the most predominant ingredient, but, cautions Cooper, “you have no idea if our product includes 1549 mg of the first ingredient and only a tiny little bit of the other ingredients.”

Even in the cases where the ingredients are broken down by weight, consumers may not know whether they should be taking 5mg or 5g of a particular ingredient, or if that ingredient will even produce the desired result.

Concludes Kunes: “The real issue is what they’re sticking in supplements might not work. There’s absolutely no bar about whether it works or not.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.