Pat Robertson’s Description Of How Reverse Mortgages Work Isn’t Accurate

Pat Robertson advises a 700 Club member during his show that a reverse mortgage is a “pretty good deal.”

As we’ve mentioned before, consumers contemplating taking out a costly reverse mortgage shouldn’t be swayed by what they hear on television, even if the person recommending the financial product happens to be well-known. Pat Robertson isn’t a financial advisor, but people do write to him seeking financial advice. Unfortunately for his many viewers who might be considering a reverse mortgage, he made some serious errors in a recent segment of his television program.

Robertson entered the reverse mortgage arena Tuesday evening when he advised a 700 Club member that if she couldn’t make ends meet, a reverse mortgage might be a “pretty good deal.”

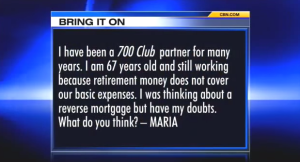

The woman wrote to Robertson’s show asking his advice regarding her financial situation.

“I have been a 700 Club partner for many years,” the woman told Robertson in an email. “I am 67 years old and still working because retirement money does not cover our basic expenses. I was thinking about a reverse mortgage but have my doubts. What do you think?”

First, the basics: Reverse mortgages allow a borrower, 62 years or older, to convert the equity in their home into a lump sum or monthly payments. A reverse mortgage is essentially a loan insured by the FHA.

First, the basics: Reverse mortgages allow a borrower, 62 years or older, to convert the equity in their home into a lump sum or monthly payments. A reverse mortgage is essentially a loan insured by the FHA.

Our colleagues at Consumers Union tell Consumerist that although many people have confidence in speaking about mortgages because they’ve had one, reverse mortgages are a very different kind of mortgage.

“These are complicated products,” Norma Garcia, senior attorney of financial services program for Consumers Union, tells Consumerist. “As we always say, it’s important to get advice from someone who has no stake in the outcome.”

Let’s break down Robertson’s advice one remark at a time:

“Here’s the deal on reverse mortgages, they will not take your house away from you as long as you’re alive and live in it,” he says into the camera.

While it’s true that the funds received through a reverse mortgage generally aren’t required to be paid back until the borrower moves from the home or dies, Robertson’s assertion that someone might not lose their home after taking out a reverse mortgage is dangerously flawed.

Consumer advocates at CU say that for many senior borrowers, the decision to take out a reverse mortgage shouldn’t center on the idea that the loan isn’t due until the borrower dies or moves from the home, but should center on whether or not this type of loan is suitable for their individual situation and life goals.

If a borrower does take out such a loan, they should be aware that there are several instances in which home owners can lose their residence after receiving a reverse mortgage, including not paying property taxes or home insurance fees and not maintaining the property.

If a homeowner fails to keep up these obligations, a lender has the option to accelerate the reverse mortgage and make the entire sum borrowed due with little notice. Such a move could leave homeowners at risk for foreclosure.

“When you do leave, you don’t have to pay it off,” he says. “But somebody has to pay it off, namely the United States taxpayer.”

While Robertson is right that someone will have to pay back the loan when the borrower dies, his vague reference to “the United States taxpayer” isn’t exactly accurate.

In fact, when a consumer who has taken out a reverse mortgage dies, their family – including a surviving spouse who may still live in the home – is often responsible for covering repayment costs or risk losing the house.

The latest changes to reverse mortgage laws have attempted to shield surviving spouses from losing their homes in many cases. However, the non-borrowing spouse will still stop receiving funds from the reverse mortgage after his or her spouse dies.

Although the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has said that the recent changes offer a bit more protection for consumers, they believe the reverse mortgage process is still a risky and expensive option – not just for the borrower but for their family.

“It’s not a good deal for the taxpayer, but for most people it’s a pretty good deal,” Robertson told the woman.

As detailed above, those tasked with repaying a reverse mortgage — usually the surviving family members — face a number of issues that make the financial product a decidedly bad deal.

As Consumerist reported last March, lenders have been found to skirt regulations meant to protect surviving consumers.

Protections include the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s regulations that require banks offer survivors the option to settle the loan for 95% of the home’s current fair market value. Because reverse mortgage loans are tied to the equity in one’s home, it is a finite amount, which can fluctuate with the changing home value.

Additionally, lenders must offer survivors up to 30 days from when the loan becomes due to decide what to do with the property, and up to six months to arrange financing.

Despite these rules, many consumers have reported they were never offered help from lenders and instead found themselves sinking further into debt.

Whether or not a reverse mortgage is a “pretty good deal for you,” as Robertson puts it, is an individual decision and might not be suitable for all consumers’ needs.

Garcia tells Consumerist that Robertson’s assertion that a reverse mortgage is a “pretty good deal for you” is a broad statement for anyone to make without knowing the details of someone’s personal financial situation.

Granted you likely won’t be around to see how things play out after your reverse mortgage comes due, but leaving a costly inheritance (or nothing at all) to your family might not be the lasting memento you had hoped to leave behind.

Robertson finished by telling the 700 Club member:

“But you need to analyze what you’re talking about and get an advisor to help you on it. But it could be a good deal for you.”

In our opinion, that final bit of advice is the only portion of Robertson’s remarks that consumers could benefit from listening to: talk to a HUD approved counselor or advisor without a stake in your finances about reverse mortgages before signing on the dotted line.

In fact, just this month a new law went into effect in California that requires reverse mortgage sellers to give prospective borrowers a self-evaluation worksheet before the required counseling session to consider key issues in deciding whether a reverse mortgage is right for them. The worksheet will make the counseling session more efficient by pre-identifying any issues of importance for discussion.

Garcia says the new law, which CU had a hand in developing, calls attention to issues that sellers aren’t likely to highlight with prospective borrowers since they often have a downside.

Here’s a video of Robertson’s advice:

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.