Medical Data Privacy Laws Don’t Actually Cover Apps, Wearables, And Other Consumer Stuff

ProPublica tells the story of how one security expert stumbled upon just how insecure that data can be. She bought a home paternity test for fun, to experiment with the tech. And when she went to look at the results, she discovered a Maury-friendly surprise: one little tweak in her browser’s address bar gave her instant access to an enormous directory containing over 6000 customers’ data.

If that seems like a glaring violation of medical data privacy law to you, well, it did to her, too.

Health data is, of course, very protected information. Under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), medical providers have to adhere to both a Privacy Rule and a Security Rule that governs what they are allowed to do with your medical information and the penalties for failing to keep that data safe.

But HIPAA isn’t universal; not all businesses have to adhere to it. Covered entities — the people and organizations that are subject to following HIPAA restrictions — include health care practitioners, health insurance companies and plans, and “health care clearinghouses,” which are businesses that process health information between other health companies.

Anyone who works with or for any of those covered entities is also subject to HIPAA. So, for example, the businesses that process medical bills (a task not usually performed in-house) or any subcontractors that work for any covered entity in any capacity are also subject to the rule.

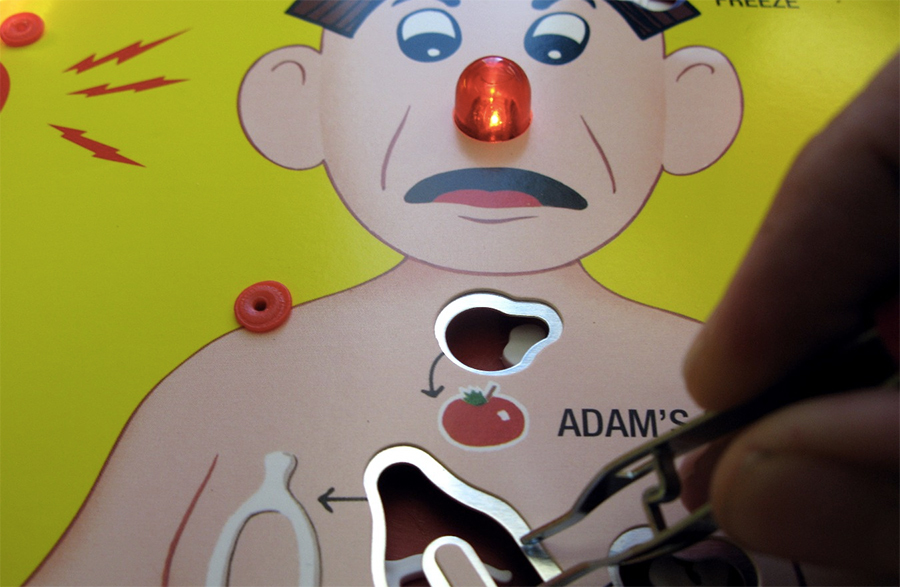

The feds offer a flowchart (PDF) to help figure out who is and is not subject to HIPAA data protections, which is helpful when it comes to actual people performing work in their various settings. It gets a little tricker, though, when your “provider” is an app or a gadget. Because those, it turns out, are not covered at all.

That’s what the security expert with the home paternity test discovered when she tried to report what she presumed was a flagrant violation of patient record security to the Department of Health and Human Services. HHS responded to her complaint more or less with a ¯\_(ツ)_/¯: nothing they could do about the easy breach, because use-at-home tests sold to consumers aren’t covered entities.

HIPAA is pretty specific about who has to be held to its standards, to minimize loopholes. But the law was written almost twenty years ago, when the idea that your doctor’s office could use a computer instead of a giant archive full of paper was still a brand-new and novel concept. There’s no place in it for apps, personal wearable health and fitness trackers, consumer-focused online repositories, home drug or DNA testing services, or any of the other innovations of the 21st century.

ProPublica points out that this is a growing problem: an unsecured database made an Australian business’s full paternity and drug test data accessible through a simple Google search in 2011. In 2014, police were able to use a publicly accessible genealogy database to match DNA to crime suspects.

In 2009, Congress passed a law updating HIPAA and requiring HHS and the FTC, which has oversight of privacy and data breaches, to work together and submit recommendations on how to handle sensitive health data that isn’t covered under HIPAA. Six years later, that report is still in progress.

Privacy Not Included: Federal Law Lags Behind New Tech [ProPublica]

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.