Sen. Calls For More Precise Data On “On-Demand” Economy & Workforce

Independent contractors are nothing new — taxi drivers paying to use a medallion, barbers renting out chairs to cut hair, local artisans selling jewelry and apparel on consignment — but the boom in online platforms that give everyone immediate access to these services and products has resulted in an “on-demand” economy and workforce whose true size and scope is unknown. In an effort to get a more accurate picture on this issue, one U.S. senator is calling on federal officials to provide more relevant data.

Independent contractors are nothing new — taxi drivers paying to use a medallion, barbers renting out chairs to cut hair, local artisans selling jewelry and apparel on consignment — but the boom in online platforms that give everyone immediate access to these services and products has resulted in an “on-demand” economy and workforce whose true size and scope is unknown. In an effort to get a more accurate picture on this issue, one U.S. senator is calling on federal officials to provide more relevant data.

In a letter [PDF] to the Secretary of Commerce and the director of the U.S. Census Bureau, Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia argues that the “federal government’s definitions, data collection, and policies” with regard to the ever-changing online economy “are still based on 20th century perceptions about work and income.”

Warner calls for more data to determine the implications of an economy in which a growing number of people are “making a living with no connection to a single employer, or without access to the safety net benefits and worker protections typically provided through traditional full-time employment.”

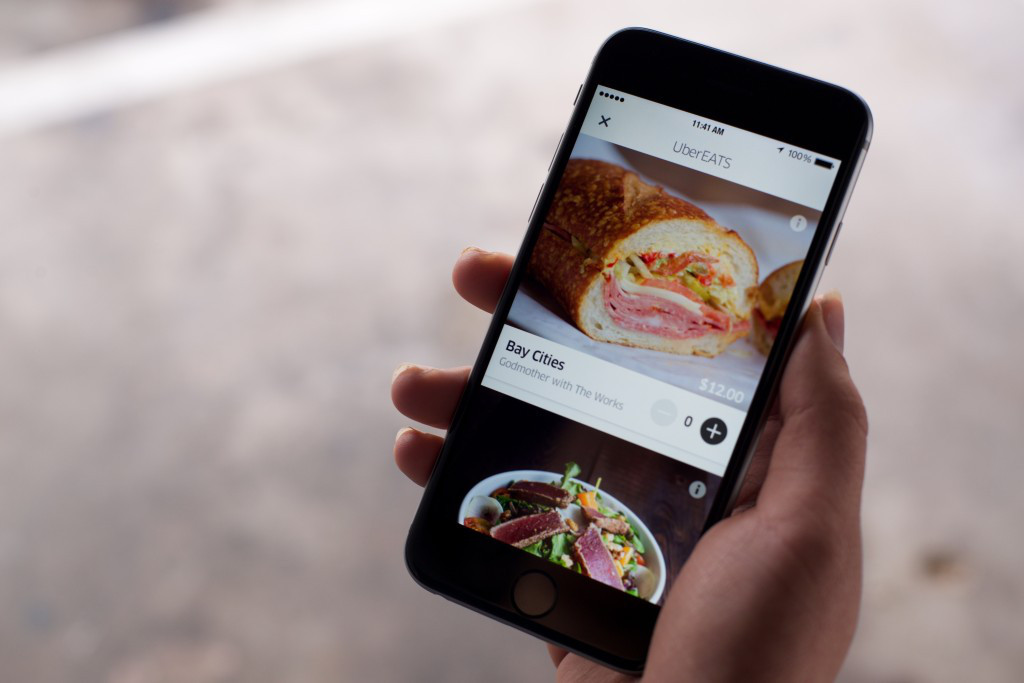

The senator acknowledges that millions of Americans are making at least some of their income through new services that use smartphones, GPS data, and other information to connect consumers with independent providers — whether it’s getting a ride from a Lyft driver, having your groceries picked up via Instacart, renting a room through Airbnb, or buying a scarf from Etsy.

The problem is — notes Warner — that we don’t really have any precise idea of how many million Americans are involved.

He points to a recent Government Accountability Office report on the “contingent workforce,” which put the number at anywhere from fewer than 5% of U.S. workers to more than one-third, all depending on what you consider “contingent.”

With the goal of hopefully arriving at a more accurate picture, Warner asks if the Census Bureau can distinguish between people who are on-demand workers for their full-time employment (ex.: a person whose Etsy shop brings in enough to earn a living) from on-demand workers who are only supplementing their primary income (ex.: an Etsy seller who makes a few extra bucks a month selling personalized napkins).

Going further, can the Census folks tell the difference between truly self-employed contractors (ex.: a livery driver operating his own car service under his own company name) and a contractor who may appear to consumers as if they are employees of a digital platform (ex.: an Uber driver whose entire business relationship with the customer is through Uber).

The senator also wants to know which existing and possible survey and measurement tools could be used to get a better understanding of the growth of this portion of the workforce.

“We need to figure out creative ways to support and encourage these innovative work arrangements,” says Warner, “and also provide some assurances that these workers have access to something more than government assistance programs to catch them if they fall.”

The letter asks the two agencies to respond within 30 days.

In July, the Dept. of Labor provided guidance for employers on the difference between an employee and an independent contractor, and noted that “Misclassification of employees as independent contractors is found in an increasing number of workplaces in the United States, in part reflecting larger restructuring of business organizations.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.