Two Big Reasons The New Broadband Standard Is Bad News For The Comcast Merger

None of the big ISPs are happy about today’s FCC vote drastically increasing the bare minimum that qualifies as “broadband.” But even though executives at Verizon, AT&T, and plenty of others are probably muttering aloud rude words in the C-suite right now, Comcast and Time Warner Cable have good reason to be more worried than most.

None of the big ISPs are happy about today’s FCC vote drastically increasing the bare minimum that qualifies as “broadband.” But even though executives at Verizon, AT&T, and plenty of others are probably muttering aloud rude words in the C-suite right now, Comcast and Time Warner Cable have good reason to be more worried than most.

The Comcast merger has been traveling a long and bumpy road since the two companies first announced their intent nearly a year ago. At first, both thought their merger was a sure thing. But as opposition has mounted, the FCC has been taking its mulling over every facet of the transaction. Today’s change, defining broadband access as download speeds of 25 Mbps or higher, now threatens Comcast’s pro-merger arguments on two new fronts.

Comcast Internet Essentials is no longer essential internet.

Comcast has been leaning heavily on its Internet Essentials program for low-income families as a reason for the FCC to approve the merger. Narrowing the digital divide is in the public interest, the argument goes, and so by expanding Comcast’s footprint nationwide the FCC also expands the number of families who have access to the $10-per-month offering.

Internet Essentials is far from perfect, but it does exist and over 350,000 families get to reap the benefits. Time Warner Cable does not have a similar program, so it’s true that letting the two companies merge would widen the number of eligible and participating families.

But for Comcast, there’s a big new problem now. Internet Essentials offers a download speed of 5 Mbps and an upload speed of 1 Mbps, for that $10 per month. And as far as the FCC is now concerned, that doesn’t qualify as high-speed broadband, and isn’t part of the solution to the digital divide. Comcast would need to increase the speed to their poorest customers five-fold (or at least promise they plan to) in order to hit the standard the commission has just set.

The new baseline has even less competition than the old baseline.

Comcast has fallen back, time and time again, on arguments that because the broadband market is highly competitive locally, that it doesn’t matter if the merger would leave them controlling way too much the nation’s high speed broadband access. They have pointed to DSL and mobile as offering competition in pretty much every market.

At speeds of 4 Mbps, that’s true. Copper-wire DSL is available in much of the country, and certainly in all the urbanized parts. But get to speeds higher than 5 or 10 Mbps, and suddenly what scant competition there is falls away.

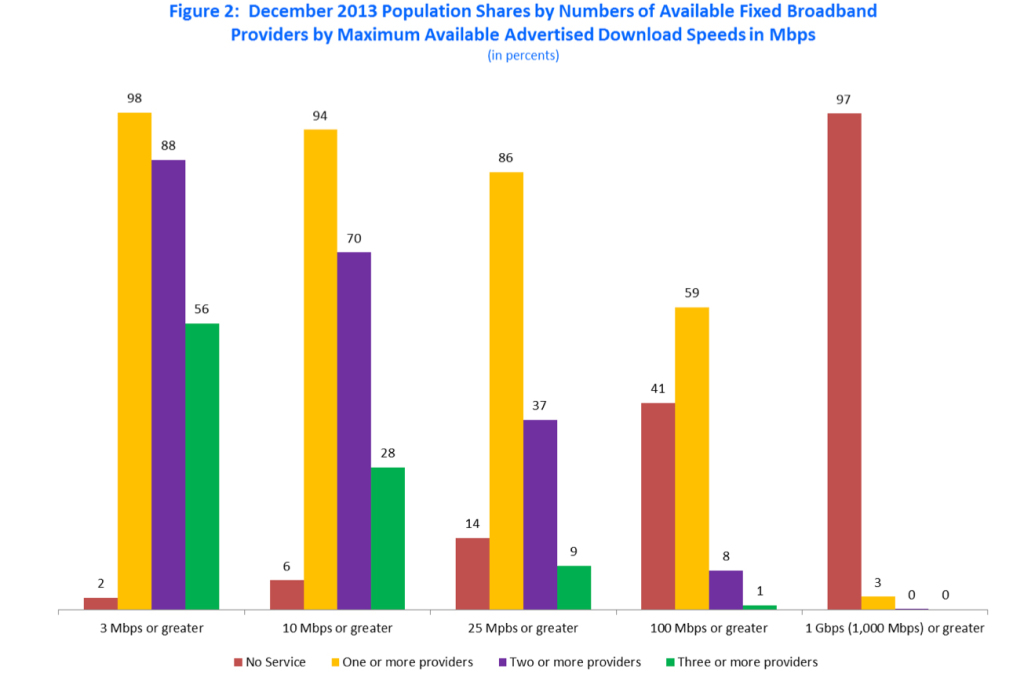

Graph from the Department of Commerce report showing how many Americans have competition for broadband services at high speeds. Spoiler: not enough.

A Commerce Department report released last December found that once you get to speeds of 25 Mbps or higher, only 37% of the country has even two providers to choose between, let alone a third nearby. And FCC chair Tom Wheeler has stressed the fact, repeatedly calling for more — not less — competition at high broadband speeds.

As opponents to the merger have been pointing out for quite some time, if Comcast and Time Warner Cable should merge, the resulting company would serve a solid half of all American customers using connections faster than 25 Mbps. Given that internet content is delivered not just nationally but globally, and that contracts with 21st century companies like Netflix are likewise national and not local, this is a huge problem.

And while mobile competition might be robust, no matter what Comcast says, wireless data is still right out as a viable competitor to wired cable or fiber internet.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.