Documents Show That Big Tobacco Has Been Interested In Pot For At Least 45 Years

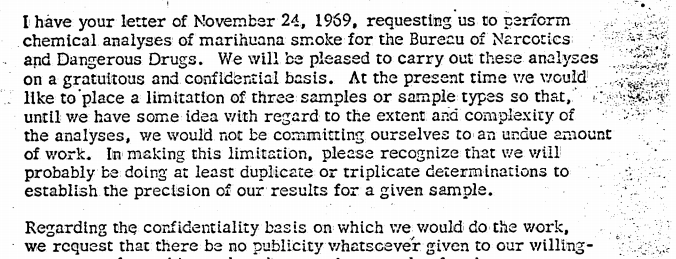

From a letter in which Philip Morris pretends that the Justice Dept. asked it to conduct marijuana research for free.

Researchers, led by Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, Director of the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at UC San Francisco, searched through the mountain of tobacco company documents that the industry was forced to make public as part of a legal action, and which are now housed in the UCSF Legacy Tobacco Documents Library.

Their report, just published in the health policy journal Milbank Quarterly, unearthed a treasure trove of correspondence on the industry’s interest and research into marijuana going back to the 1960s.

“From all I can gather from the literature, from the press, and just living among young people, I can predict that marihuana smoking will have grown to immense proportions within a decade and will probably be legalized,” reads a note from a professor at the University of Virginia (go Hoos!) who supervised the Philip Morris Fellowship in Chemistry to the manager of chemical and biological research at the company’s research laboratories. “The company that will bring out the first marihuana smoking devices, be it a cigarette or some other form, will capture the market and be in a better position than its competitors to satisfy the legal public demand for such products. I want to suggest, therefore, that you institute immediately a research program on all phases of marihuana.”

Eventually, Philip Morris reached out to the Justice Dept. to figure out how it could research pot without getting in trouble — and more importantly without the public knowing about it, presumably out of fear that this could damage the company’s reputation and tip PM’s hand to the competition about what it was working on.

A 1969 Philip Morris memo mentions that the Chief of the Drug Sciences Division at the DOJ was “most anxious to have the smoke from Cannabis sativa analyzed the way smoke from tobacco is analyzed.”

This later led to a back and forth where a deal was made that the DOJ would officially request that PM undertake this research that the government could not afford to do.

“We will be pleased to carry out these analyses on a gratuitous and confidential basis, reads a Dec. 1969 letter from a Philip Morris exec to the DOJ. “[W]e request that there be no publicity whatsoever given to our willingness to perform this work and to receive samples for that purpose.”

The DOJ official wrote back that he didn’t see a reason this confidentiality couldn’t be honored.

In a letter to Philip Morris dated Christmas Eve 1969, the DOJ official suggests that the best way to obtain samples confidentially would be to avoid the traditional route of applying with the Psychotomimetic Advisory Committee, “since that application then becomes rather well known.”

Instead, he suggests that Philip Morris apply to the District Director of Internal Revenue for a tax stamp as a Class V researcher.

“Perhaps it would be of value if I were to visit your laboratory and discuss with your people some of the methods used, size of sample needed, etc.,” reads the letter, “so that when you receive the tax stamp, I can have enough information to make the request for cannabis in my name, thus preserving your anonymity.”

In early 1970, the Philip Morris execs who made this deal with the DOJ then took the idea to the company’s top management, once again employing the pretense that it was not an internal, corporate idea, but a request being made from the Nixon administration.

“We can hardly refuse this request under any circumstances,” reads the memo. “[W]e regard it as an opportunity to learn something about this controversial product, whose usage has been increasing, so rapidly among the young people.”

The letter goes on to explain that, hey, maybe we should consider being in the marijuana business:

“We are in the business of relaxing people who are tense and providing a pick up for people who are bored or depressed. The human needs that our product fills will not go away,” explains the memo. “Thus, the only real threat to our business is that society will find other means of satisfying these needs.”

Thus the notion of others providing marijuana as a competing product “strongly suggests that we should learn as much as possible about this threat to our present product.”

And in fact, among many younger Americans, pot is more popular than tobacco, with nearly 1-in-4 high school seniors having smoked marijuana while only about 1-in-6 had smoked cigarettes. In the last 15 years, the rate of high schoolers smoking pot has maintained while the rate of cigarette smoking among this age group has been cut in half.

Yet because it remains illegal in the eyes of the federal government, the tobacco industry isn’t officially working on any sort of marijuana products.

“Our companies have no plans to sell marijuana-based products,” a spokesman for Altria Group Inc., the parent company of Philip Morris, tells the L.A. Times. “We don’t do anything related to marijuana at all.”

Likewise, a rep for R.J. Reynolds tells the Times that research that took place in a previous era doesn’t matter now.

“I cannot begin to speculate on the thinking of management more than 20 years ago,” said the rep. “Regarding the current cannabis market, we are not pondering any expansion or involvement in that market, nor do we conduct any research into marijuana.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.