Comcast and Time Warner Cable have done their parade in front of the House and Senate to state their case publicly for why they should be allowed to merger into a truly massive mega-company. But now, it’s time for the investigation that really matters, as regulators at the FCC and the Department of Justice start looking into whether or not this deal is good for the public interest… or violates antitrust law.

Comcast and Time Warner Cable have done their parade in front of the House and Senate to state their case publicly for why they should be allowed to merger into a truly massive mega-company. But now, it’s time for the investigation that really matters, as regulators at the FCC and the Department of Justice start looking into whether or not this deal is good for the public interest… or violates antitrust law.

A Matter of Antitrust

Lots of law in the U.S. is concerned with making up for harms after the fact — if you behave in a certain bad way, you have to pay a fine, or face a criminal charge, or get the pants sued off you.

Lots of law in the U.S. is concerned with making up for harms after the fact — if you behave in a certain bad way, you have to pay a fine, or face a criminal charge, or get the pants sued off you.

Antitrust law, though, doesn’t just deal with penalizing companies for behaving in illegally monopolistic ways. It also allows the courts to try to prevent problems in advance, by looking at a proposed merger and projecting out if that transaction would be likely to result in anticompetitive harms that would outweigh possible benefits.

The long approval process for the merger of Comcast and Time Warner Cable is only a few steps into its long and twisted road. The FCC has received the companies’ official filing, and company executives and pro- and anti-merger experts have testified at both House and Senate committee hearings. With all of that, there’s still another player waiting in the wings.

What The DoJ Is Looking For

The Justice Dept. — specifically, its Antitrust Division — is the person at any corporate marriage that everyone side-eyes when it gets to the “speak now or forever hold your peace” part. Because it very well could start jumping up and down while waving firecrackers, stopping the happy couple from saying, “I do.”

In legal terms, the DoJ would do that by filing a complaint to block the acquisition. Such a complaint seeks “to permanently enjoin a proposed joint venture and related transactions.” The legal teams making the complaint then have to outline what likely bad outcomes they are trying to prevent by blocking the business deal.

Those likely bad outcomes are called theories of harm. They are the plaintiffs’ theories about what likely harms will result — to consumers, to other businesses, to anyone and everyone who has something at stake.

No complaint has yet been filed regarding the Comcast and TWC merger, and until and unless one is filed, it’s impossible to know precisely what case will be made.

That said, based on the arguments already made for and against the merger, we can take some educated guesses at a number of the theories of harm that could be proposed.

“Bad” Is The Baseline…

Any complaint has to start by looking at the current conditions on the ground, and then looking at how another merger could make those conditions worse, and how.

(If a merger made conditions better, then the deal wouldn’t be harmful and no complaint would need to be made.)

That means the 2011 Comcast/NBCU merger case and all its back-and-forth filings remain both relevant and instructive. It makes sense to look at what the DoJ’s concerns were three years ago, and to see which of them have or have not come to pass.

It also makes sense as kind of a shortcut, in a sense.

Antitrust expert Allen Grunes, who recently testified before members of the House about the merger, explained to Consumerist that any “Existing theories in the toolkit still apply.”

That means that all of those concerns about consequences from the vertical merger of Comcast and NBC haven’t mysteriously vanished into the ether. If the horizontal merger of Comcast and TWC can exacerbate those conditions, then those theories are once again relevant.

…And “Worse” Comes Next.

There are two big buckets of anti-competitive behavior that the potential harms could fall into. One is consumer-facing and the other has more to do with business effects.

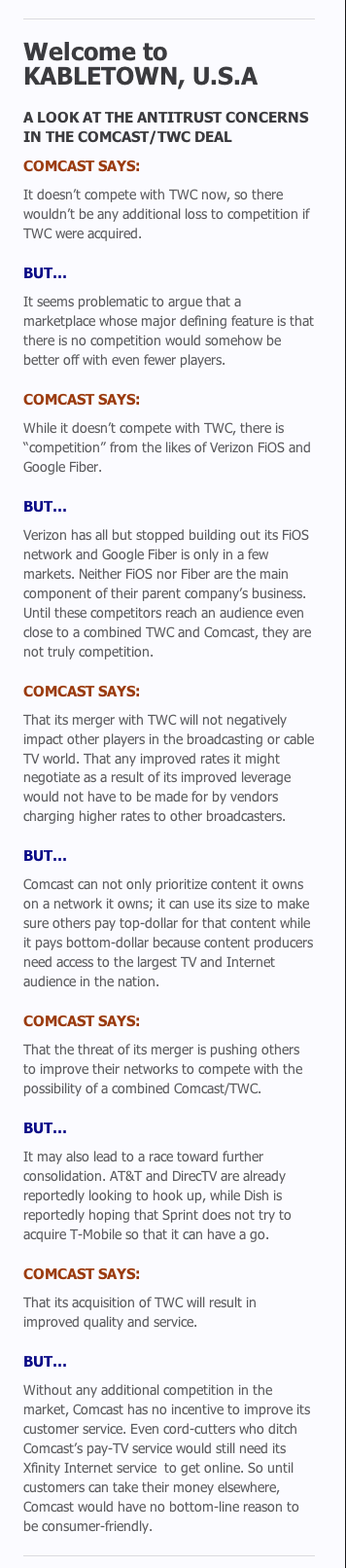

As far as the consumer is concerned, we’ve been here before. Comcast’s talking heads repeat over and over the mantra that Comcast and TWC do not compete for consumers in any of the same geographic areas. And that’s true!

It’s terrible — a bad baseline from which conditions can get worse — but technically true.

Geographically, cable competition is already mostly non-existent, and that’s unlikely at best to change anytime soon.

However, the DoJ found in 2011 that even the tiniest threat of potential competition improves conditions for consumers.

For example, in the 2011 complaint the DoJ mentions:

- Online video competition (like Netflix) spurred cable companies like Comcast into “improving existing services and developing new, innovative services for their customers,” particularly in relation to streaming video and user interface improvements.

- Competition from the “phone” companies (Verizon and AT&T) “provoked incumbent cable operators across the country to upgrade their systems” to offer both more TV channels and triple-play packages.

Thus, Comcast claims that mobile data service is sufficient competition (it’s not). They also claim that companies like Verizon and Google, with FiOS and Fiber respectively, are actual competition, even though Verizon’s build-out of its FiOS network has stalled and Google is still only widely available in one or two markets.

So while that hint-of-competition argument may hold true in a handful of cities, it falls short.

According to Grunes, true competition doesn’t just mean that there is one little business somewhere in the country doing the same thing.

When it comes to letting other competitors — new entrants — into the field, “entry means profitable entry,” Grunes explained.

That means that competition needs to be possible from an actual business, operating as a business, making money.

So the fact that Google Fiber — a sideline business to Google’s much bigger, more profitable search engine and ad platform — exists in a handful of markets does not necessarily make it a legitimate competitor to Comcast or TWC.

And as it currently stands, starting an actual, new, competing nationwide company to Comcast is so challenging as to be nearly impossible.

And that leads us back to businesses…

Make Things So Difficult Nobody Wants To Bother

It seems to go almost without saying that broadening Comcast’s reach across the country would increase the pressure its vertical leverage can exert. And they’ve got power over both the TV and Internet sides of their business.

Over in TV land, back in 2011 the DoJ pointed out that the merger of Comcast and NBCU would give Comcast the means and the motive to withhold content from other distributors, including cable, satellite, phone, and fiber companies.

In antitrust terms, that theory is called input foreclosure. The bigger Comcast gets (by gobbling up TWC’s customers), the more power it has both to privilege content it owns on a distribution network it owns, and to withhold or threaten to withhold that content from other distribution networks.

But as counterintuitive as it may sound for a business worth billions of dollars, TV isn’t the biggest problem.

Comcast is already such a large and entrenched player in TV that, while it can certainly make the costs of doing business higher for advertisers, networks, and consumers, it’s still playing the role of the devil you know.

Over in Internet-land, though, it’s a different story.

The merger is really all about the Internet, and all about the information that now gets delivered digitally.

Where TV content companies are themselves consolidated into a handful of major players and another handful of minor ones, genuine start-ups are still an actual thing on the Internet, and companies can go from “some guy’s idea” to “billion-dollar enterprise” in just a few years. Netflix, Apple, Hulu, Amazon, and YouTube are all major players in content distribution, now… and yet, the landscape as we now know it only really began to take off in 2008. A lifetime just five years ago.

When critics express the idea that the Comcast and TWC merger can “kill innovation,” they’re talking about incumbent companies’ ability to exclude new companies from joining their party. And it’s really cheap and really easy for big companies to do just that.

Because Comcast gets to double dip with content, traditional delivery, and broadband access, it’s incredibly straightforward for them to interfere with new competitors’ ability to do business. All they have to do is sit there not being particularly accommodating until they get paid off.

In antitrust terms, this harm is customer foreclosure: when competition suffers because rival companies can’t get access to the customers they need to thrive.

But wait! You also get…

As if the negative effects on consumers and on all of the businesses in the long chain of TV production and internet video weren’t bad enough, there are still more side-effects to the joining of Comcast and TWC.

It creates an arms race, for starters. When one company gets bigger, the few others that are left need to go to extraordinary measures to try to compete. Like, say, AT&T and DirecTV considering a merger of their own.

And of course, with even less competition, there’s no reason to improve customer service, stop increasing prices, or do away with customer-unfriendly measures like data caps.

Comcast’s track record of keeping all of those little promises they make to regulators is abysmal. When they do meet their “behavioral remedies,” as they are known, they stick to the minimum agreement and then endlessly brag about how awesome they are for doing it.

In Conclusion…

Business finds itself with an easy analogy in the natural world: a big planet will draw tiny moons and satellites into its orbit unless another force intervenes, and the little ones can’t do a thing about it. They just zoom around the big planet forever… or until they crash into it.

But in U.S. law, there is another force. The Antitrust Division can fight back, laying out its case for the dozens of harms, large and small, this merger could cause up and down the entire chain.

Businesses and consumers can still avoid being drawn inexorably into Comcast’s orbit… as long as this case doesn’t go down just like last time.