Two Big Reasons The Comcast And Time Warner Cable Deal Is Bad For Consumers

Yesterday, Comcast and Time Warner Cable announced a $45 billion merger deal. Consumer advocacy groups (and consumers) were less than thrilled about Comcast’s big news, and ardently called on the FCC and the Justice Department to alter or prevent the buyout.

Yesterday, Comcast and Time Warner Cable announced a $45 billion merger deal. Consumer advocacy groups (and consumers) were less than thrilled about Comcast’s big news, and ardently called on the FCC and the Justice Department to alter or prevent the buyout.

As Comcast and Time Warner keep pointing out, though, the two companies really don’t operate in any of the same markets. While many of us are already subject to a local monopoly of one or the other, a union of the two doesn’t change that circumstance for better or for worse with any households or subscribers. So would this particular corporate marriage really make anything worse?

Yes, yes it probably would. And most of the reasons fall into one of two big buckets of issues.

Extreme industry consolidation

We all know that Comcast is the biggest cable company in the country. But how big is big?

Really big. Currently, Comcast has about 21 million subscribers. Time Warner Cable and its 11 million customers are the next largest cable company. Third and fourth place go to Cox and Charter, with roughly 6 million and 4 million subscribers respectively.

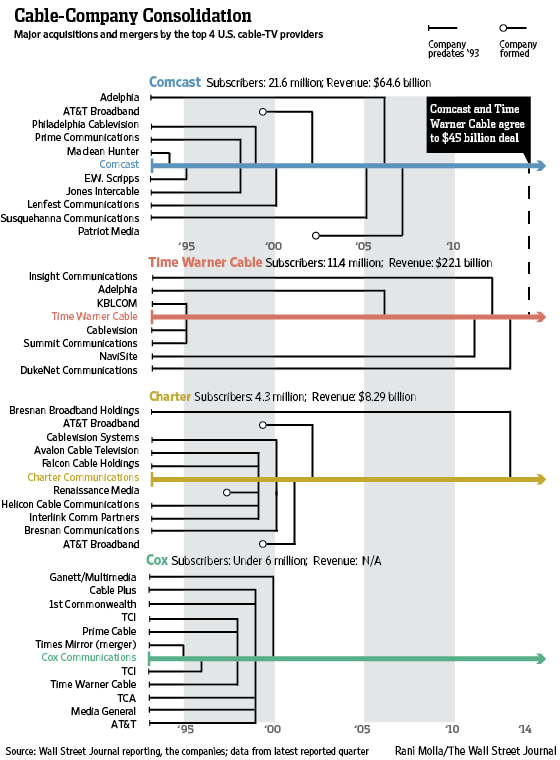

Much in the same way that decades of rampant consolidation have left us with fewer, larger banks than ever before, we now have fewer cable choices than ever before. Over the past few decades local companies merged into regional companies, which merged into bigger regional companies, which today have merged into just a handful of semi-national operators.

The Wall Street Journal yesterday published a chart making a clear visual example of consolidation over the past twenty years:

20 years’ worth of cable consolidation, via the Wall Street Journal

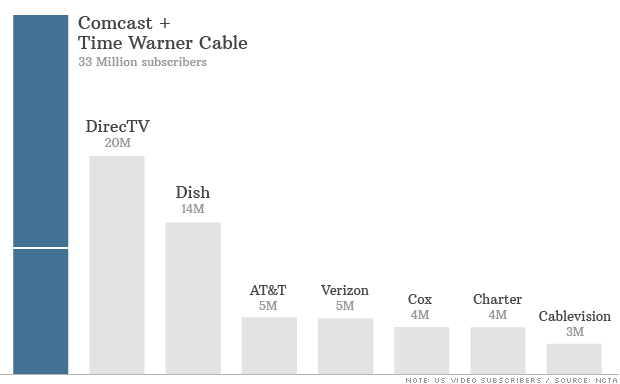

Comcast picking up Time Warner’s subscribers would bring it to about 30 million customers, five times the number of the next-biggest competitor. They’d also dominate 19 of the country’s 20 largest cities. But of course, that’s just cable. What about satellite? What about fiber? Surely these are large, viable competitors?

Well, yes. Sort of. But Comcast–and a unified Comcast-Time Warner–will continue to dwarf them all. CNMoney points out that the 30 million combined consumers would in fact be a full third of all the cable or internet subscribers in the nation:

Comparison of subscriber bases, from CNNMoney

A company that large has enormous clout with everyone. Comcast will have enormous leverage when negotiating content carriage contract deals and rates, which in turn influences how much a consumer has to pay.

And bringing in satellite and fiber competition brings us to the second major merger problem: broadband.

It’s not about TV, it’s about the future of internet access.

Cable subscription went nowhere but up every single quarter for decades… until 2008. That’s the year that Netflix opened up its streaming-only service, and Hulu launched just a few months later. Then the economy tanked. With new easy streaming options available, cost-conscious cord-cutters couldn’t justify a hundred-dollar cable bill anymore.

Cable TV subscriptions stopped growing, flattened out, and then began to drop. That’s bad for a cable company! But since consumers now get more and more of their media from the internet, and the cable companies also control huge swaths of the broadband access in the United States, there’s been plenty of room for repositioning.

Cord-cutters who are still streaming something need to get their internet fix somewhere, and it’s been the cable companies. Fiber’s small potatoes in comparison, and satellite internet is an unreliable and expensive option mostly reserved for rural areas.

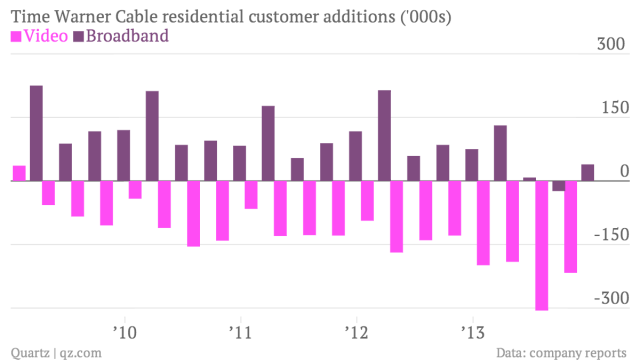

In January, Quartz took a look at how Time Warner has been hemorrhaging pay TV customers while also scooping up broadband users:

Five-year subscriber trends at Time Warner Cable, from Quartz

Bringing Time Warner into the Comcast fold wouldn’t just mean Comcast would control about 30% of the nation’s paid TV. It would mean Comcast could control about 30% of the country’s internet access. And that is a problem.

Internet competition is all but non-existent in a huge number of markets, and that’s no accident: the cable lobby likes it that way. The absence of a reliable alternative means a company can let its service plummet and its rates skyrocket, and there’s not much a consumer can do about it. When only one company will wire and service your area, you either use them or unplug entirely. The lack of competition already has bad results for end-users.

But it could still get worse. Net neutrality regulations forced broadband ISPs to provide an even playing ground for other companies’ content, but as of January, those regulations no longer exist. While ISPs are promising to play nice for the meantime, without a new rule in place those oh-so-noble promises are all but certain eventually to drift into obscurity.

Comcast is required to obey the now-vacated net neutrality regulations until January 2018, as part of the terms of their acquisition of NBCUniversal in 2011. Four years can fly by awfully quickly in a swiftly changing marketplace, though, and Comcast–owner of NBCUniversal, partial owner of Hulu, major industry player–has a great deal of incentive to promote their own services over others.

Comcast’s bid to buy Time Warner isn’t about what channels you can watch or how you get Game of Thrones. It’s about the internet getting slower, less open, and more expensive. And that’s a bad deal for us all.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.