How American Must A Product Be To Be Labeled “Made In The USA”?

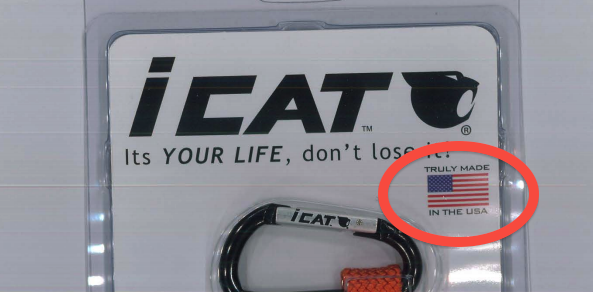

The FTC says that not all E.K. Ekcessories products carrying the “Truly Made in the USA” logo met the agency’s guidelines for using that phrase.

While there are federal standards for what qualifies as “Made in America,” there is no vetting or certification process that goes on before that label can be applied.

So a company could slap a made-in-USA sticker on its products and hope it doesn’t get caught, much like E.K. Ekcessories, an outdoor accessories company that the FTC recently accused [PDF] of deceptively marketing its products with labels like “Truly Made In the USA,” and statements on its website that its products were made at the company’s facilities in Utah.

[UPDATE: In e-mails to Consumerist, E.K. Ekcessories clarifies that it never had any intention to deceive consumers and says only a small number of its components are imported and that all assembly in done in the United States. Though E.K. says it believes the guidelines determining what counts as “Made in U.S.A.” are too strict, the company claims to now be in full compliance with the FTC standards.]

That company has since settled with the FTC and agreed to stop falsely marketing its imported products as made in America, but who knows how many other products are out there just waiting to be caught in the same lie?

So what does it take to actually count as being made in the USA?

SLINGING LINGO

First off, there is no specific language that manufacturers must use. To the feds, statements like “Made in the USA” and “American-made” are effectively the same. They communicate to the consumer the notion that the product was produced within the 50 states, the District of Columbia, or in U.S. territories.

Additionally, the made in America claim doesn’t need to be explicit. The FTC gives the following example:

A company promotes its product in an ad that features a manager describing the “true American quality” of the work produced at the company’s American factory. Although there is no express representation that the company’s product is made in the U.S., the overall — or net — impression the ad is likely to convey to consumers is that the product is of U.S. origin.

References to America in a product or brand’s name is a slightly trickier affair. For instance, the FTC likely won’t go after a product called USA Joysticks even if said joysticks are made in Vietnam, but if that same product were to be called “Made In USA Joysticks,” then it would likely have to fall into the made-in-USA guidelines.

VIRTUALLY ALL-AMERICAN

Those guidelines require that a product carrying a “Made in USA” marketing claim with no immediate and clear qualifications must be “all or virtually all” made in the U.S. or its territories.

The FTC takes “all or virtually all” to mean that all significant parts and processing that go into the product must be of U.S. origin. Any foreign supplied parts or ingredients should be negligible.

It gives two examples to show how it determines whether foreign parts constitute a negligible portion of the end product. The first example is a gas grill that is assembled in the USA and whose only foreign-made parts are some tubing and the knobs for controlling the flame. In this case, the FTC says that the knobs and tubing are insubstantial enough and a Made In USA claim would be okay.

The second example is a Tiffany-style lamp where everything but the base of the lamp is supplied by U.S. companies. To the FTC, the base is too integral and substantial a portion of the end product, and so an unqualified Made In USA claim would not hold up to scrutiny.

FOREIGN RESOURCES

Then there is the question of where the raw materials for various components came from. Again, this depends on how much of the end product is made up of those raw materials. A computer that has some parts which contain imported metal would likely pass muster, but a wrench made mostly out of imported metal would probably not. This does not necessarily hold true for clothing with the Made In USA label (see below).

For products that are assembled in the U.S. from a mix of foreign and domestic parts, manufacturers may make qualified marketing claims like “Made in USA of U.S. and imported parts,” “Assembled in the USA from Italian leather and Mexican wood,” or “60% U.S. Content.”

However, the FTC advises companies to tread lightly when making these kinds of qualified claims, as they still imply to consumers that a large portion of the manufacturing was done stateside.

A GUY WITH A SCREWDRIVER IS NOT A MANUFACTURING PLANT

The Commission warns against using the “Assembled in USA” claim for products where the only assembly done in America is what the FTC refers to as “screwdriver” assembly. That’s when all the major parts are already put together elsewhere then shipped to the U.S. to be quickly put together. Basically, if the work being done is no more complicated than putting together some IKEA shelves, it probably doesn’t qualify as “Assembled in America.”

CAR COMPONENTS

One industry that has been prolific in touting “American made” claims is the automobile industry. The American Automobile Labeling Act requires that each vehicle manufactured for sale in the U.S. bear a label disclosing where the car was assembled, the percentage of equipment that originated in the U.S. and Canada, and the country of origin of the engine and transmission.

Even with these additional requirements, any automaker or clothing company making a “made in America” claim in its advertising would be held to the same criteria as other products.

THE CLOTHES ON YOUR BACK

The Textile Fiber Products Identification Act and Wool Products Labeling Act actually requires Made in USA labels on most clothing and other textile or wool household products if the final product is manufactured in the U.S. of fabric that is manufactured in the U.S., regardless of the country of origin of materials earlier in the manufacturing process. So an all-wool sweater may be made from wool that was grown entirely on another continent, but as long as the sweater itself is wholly made in the U.S., it gets the Made in USA label.

Textile or wool products that are partially manufactured in the U.S. and partially manufactured abroad must be labeled to show both foreign and domestic processing.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.