We Are In The Era Of “Nightmare” Bacteria And Nobody Seems To Care

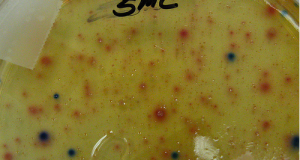

On March 5, 2013, the Centers for Disease Control issued a press released titled “Lethal, Drug Resistant Bacteria Spreading in U.S. Healthcare Facilities.” The warning that followed was dire. Drug-resistant organisms called carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE, were not only spreading more rapidly through U.S. hospitals, they were becoming more resistant to so-called “last-resort” antibiotics. “CRE are nightmare bacteria,” said CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden. How nightmarish? According to data from the CDC, 1 in 2 patients who contract a bloodstream CRE infection will die. That’s an ominous statistic, but it might not even be the scariest fact about CRE.

CRE bacteria are unusual in that they can transfer antibiotic resistance to other bacteria. This means that it is possible for a CRE organism to spread its resistance to bacteria like E. coli, the most common cause of urinary tract infections in otherwise healthy people. Treatment for this type of infection is usually straightforward, but once the bacteria become drug-resistant, the treatment options are effectively gone.

HOW THE “NIGHTMARE” WORKS

According to information from the CDC, a few CRE bacteria are introduced into the system of a patient at a hospital, or in the community through a cut or scrape or other vector. The infected patient shows signs of infection and is treated with standard antibiotics. At this point, normal bacteria are killed by the antibiotics, while the CRE flourish. Then, the CRE can spread their resistant characteristics to other bacteria present in the patient’s body. Those bacteria, now essentially untreatable, can then spread to other patients or members of the community and thus, the cycle continues.

Currently, CRE infections most commonly occur in hospital settings, through the transfer of bacteria between patients or through shared equipment and via the hands of medical staff, but FRONTLINE’s new documentary, Hunting the Nightmare Bacteria examines several cases of antibiotic resistant infection, including the haunting case of 11-year-old lung-transplant recipient Addie Rerecich who acquired her initial infection not from a hospital, but out in the community, possibly through a scraped knee.

All of this adds up to a frightening picture, but in an opinion piece for the Washington Post, David E. Hoffman, the Post correspondent who investigated the “nightmare bacteria” for FRONTLINE, bemoans the public’s lack of interest in the issue.

“This is not a threat that causes people to jump out of their chairs. It always seems to be someone else’s problem, some other time. We ought to snap out of our long complacency,” Hoffman says.

The documentary, which begins airing tonight on PBS stations, also takes an inside look at a CRE outbreak at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (in which 19 patients contracted a resistant infection and seven died) before examining the business decisions and economic pressures that are driving the current research, production, and use of antibiotics.

“The world is entering a post-antibiotic era. Doctors tell me there are patients for whom we have no therapy. The bacteria are growing stronger, and the drug pipeline is drying up,” Hoffman says.

Of course, to a certain extent, the reason we don’t leap from our chairs that the problem doesn’t seem new. As Hoffman points out in his Washington Post piece, Alexander Fleming addressed the threat of antibiotic resistance in his 1945 Nobel Prize lecture.

“It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them, and the same thing has happened in the body,“ Fleming warned.

“Bacterial resistance is largely inevitable, “ a representative from the CDC tells FRONTLINE, “but it’s also something that we have certainly helped along the way. We have fueled this fire of bacterial resistance. These drugs are miracle drugs… but we haven’t taken good care of them. In overusing these antibiotics we have set ourselves up for the scenario that we find ourselves in now, where we are running out of antibiotics.”

So, if we suspected in 1945 that antibiotics had a limited lifespan, why are we running out? Where are the new antibiotics? What are the drug companies doing to develop new treatments? Turns out the answer is troubling. According to FRONTLINE, just as the problem of resistance was peaking, many drug companies were pulling out of antibiotic research.

Dr. John Rex, V.P. Clinical Research for AstraZeneca, explains:

“If you need an antibiotic, you need it only briefly. Indeed that’s the correct way to use an antibiotic. You use it only briefly, and from an economic standpoint of a developer that means you are not getting the return on the investment you’ve made…. It can easily cost up to a billion dollars to bring a new drug to the market, and the initial reaction to it is, that’s great; let’s not use it. Let’s use it as little as possible. “

In their piece, FRONTLINE chooses to focus on Pfizer, a leader in the development of antibiotics before they exited the field in 2011. Dr. John Quinn, part of a team that was working on developing treatments for antibiotic resistant germs at Pfizer’s Groton, CT, research facility describes his experience:

“In 1983, when I finished my training, almost every company had an antibiotic development team, and by the time I landed at Pfizer in 2008 we were really down to three big guys and some smaller companies, biotechs and so on. And I think all of us felt, you know, that we had a moral obligation to continue to work in this area. There was a pressing clinical need, most companies had abandoned the field, and we were still in the game. We were proud to still be in the game.”

But in 2011, with the patent expiring for Pfizer’s blockbuster cholesterol drug Lipitor and Pfizer’s stock down, Dr. Quinn got an email on his Blackberry about an emergency meeting.

“Can’t be good,” he tells FRONTLINE. “So I called in for the meeting and was told that the announcement had been made, that the Groton facility was going to be closed.“

Dr. Brad Spellberg, infectious disease specialist and author of the book Rising Plague, says, “Here’s a large company saying ‘I can make billions off of cholesterol drugs, blood pressure drugs, arthritis drugs, dementia, things that I know patients are going to have to take every day for the rest of there lives. Why would I put my R&D dollars into the antibiotic division that isn’t going to make me any money, when I can put it over here… where it’s going to make a lot of money for the company? I answer to the shareholders.”

FRONTLINE asked Dr. Charles Knirsh, V.P. Clinical Research for Pfizer, to explain the decision to discontinue the research into CRE and other drug-resistant bacteria.

“These are portfolio decisions about how we can serve medical need in the best way,” Dr. Knirsh said. “We want to stay in the business of providing new therapeutics for the future. Our investors require that of us. I think society wants Pfizer to be doing what we do in 20 years. We make portfolio management decisions.”

Despite all of this, we continue to use antibiotics as if we will never run out. Public health officials cited by FRONTLINE say that up to half of antibiotic use in the United States is either unnecessary or inappropriate, and in a report published last year, our coworkers at Consumers Union found that the major user of antibiotics in the United States today is not the medical profession, but the meat and poultry business.

“Some 80% of all antibiotics sold in the United States are used not on people but on animals, to make them grow faster or to prevent disease in crowded and unsanitary conditions,” writes Consumers Union, one of many groups — including several lawmakers in D.C. — who believe that the best way to preserve antibiotics for treatment of disease in people is to drastically reduce or eliminate the non-medical use of these drugs on animals.

For more information on Consumers Union’s campaign to curb the use of antibiotics in food production, click here.

Hunting the Nightmare Bacteria, premieres Tuesday, Oct. 22, at 10 p.m. on your local PBS station, and will later be made available for online viewing on PBS.org.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.