Why Was Gas So Expensive?

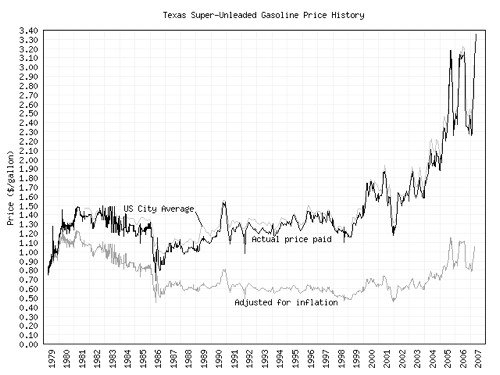

Did you know that gas price gouging almost never occurs as prices rise? Rather, it’s most often when dealers keep prices artificially high even as their costs fall. As gas costs were near $5 a gallon until falling and oil companies earn around $100 billion each year, it’s a good time to question what really goes into the price of gas. The numbers on the gas station sign hide a complex set of transactions. Before gas can power your car, it must be discovered as crude oil, traverse three markets, and be refined from crude into gas. Inside, we’ll explain the three markets, walk you through the role of refineries, and show how oil companies use creative tactics to manipulate gas prices…

The Three Markets: Contract, Spot and Futures

Both oil and gas are traded on three markets: the contract market, the spot market, and the futures market. Each is influenced by different factors and impacts the price of gas at different stages of production. Unlike the futures market, the contract and spot markets are not the kind of markets found on Wall Street; they are informal networks of businesspeople.

The Contract Market

Though it seems like oil companies spend most of their time ruining your day by raising the price of gas, their primary business is exploration. Once an oil company finds a field and coaxes it into producing crude, it takes that unrefined oil and sells to refiners. The vast majority of oil is sold by contracts. A veritable orgy of contracts signed between oil companies and dealers, oil companies and refiners, refiners and independent dealers predetermine the fate of most oil and gas.

Refiners plan their purchasing and refining activity to ensure that these contracts are fulfilled. In exchanged for this privileged standing, refiners charge contract customers a premium.

The Spot Market

Need some extra oil? Got a spare barrel you need to sell today? The spot market is for you. The spot market fills the gap left by the contracts market. When a refiner needs extra oil to meet its contracts, they find people with surplus oil on the spot market. Unlike the contract and futures markets, which trade pieces of paper, the spot market involves the trade of actual barrels.

The best deals are often found on the spot market. Since neither the buyer or seller is locked into a prearranged deal, the laws of supply, demand, and free market are mostly in effect.

The Futures Market

Crude oil is the bees knees of the American Mercantile Exchange. A futures contract might stand for 1,000 barrels of West Texas Intermediate to be delivered at Cushing, Oklahoma. The futures market represents that collective state of the oil market at any particular moment. When you hear reporters talk about the price of oil reaching $100 per barrel, they’re talking about the futures market. Because fluctuations on the futures market are driven by information, its prices guide the contract and spot markets.

The people buying and selling futures rarely, if ever, collect on their contracts; a seven year period saw 5 billion barrels traded, of which only 31,000 were ever delivered.

Refineries

Refineries are the temples where crude oil gets Bar Mitzvah’d into gas. Shifts in the refining world over the past two decades have helped ratchet up the price of gas. In the early 80’s, there were over 350 refineries, mostly owned by the oil companies. The oil companies didn’t see refining as a place to generate profit, but as an integral part of a larger operation.

By 2002, there were only 153 refineries, and most of them were no longer controlled by the oil companies. Refineries are now held privately and independently, and as with any independent businesses, profit is key. It is in the refiner’s interests to supply only as much gas as is absolutely needed to stay on the profitable side of the supply and demand curve.

Gas emerging from a refinery is sold at what is known as the ‘rack price.’ The rack price is the cost of gas to dealers, and it is generally influenced by the spot and futures market. The rack price is also where branded gas begins to exert a price premium.

Branded gas from Exxon-Mobile, BP-Amoco, etc, isn’t different from the unbranded gas found at Joe Schmoe’s Gas Shack. Still, there are several costs associated with branding gas. The brand name carries a premium, since people might associate it with quality, and not grossly overcompensated executives. Branded gas is also sold under contract, giving buyers long-term stability that can’t be duplicated by unbranded gas. Oil companies also add value to branded gas by providing ancillary benefits that command a price premium, like branded advertising and branded credit cards.

Refiner pricing strategies are almost as complex as the mating rituals of the red-sided garter snake. Though refiners want to maximize their profit, they don’t necessarily want to gain additional market share. Refining capacity can’t simply be ramped up on demand. Acquiring and refining crude oil takes considerable time, leading refiners to take a slow and steady approach to business. First and foremost, refiners care about fulfilling their contractual obligations. Leftover gas can be sold for profit on the rack.

If a refiner’s rack price is consistently too high, dealers will take their business elsewhere when their contracts expire. If the rack price is too low, buyers might swamp the refiner, leaving it unable to meet its contractual obligations.

To ensure pricing continuity, refiners used to call each other and share pricing information. Activist judges on the Supreme Court called this “collusion.” The refiners, unfazed by the justices, came up with a crafty alternative: publicly posting their rack prices. Somehow, the Ninth Circuit Court found this to be illegal, too. Nobody knows how refiners discuss their pricing arrangements nowadays, but we wouldn’t be surprised if it involved a members-only group on Facebook.

Gas Stations

Ah, gas stations. Nourishers of our cars, wellspring of our rage. Gas stations are not all alike. Some are owned outright by the oil companies, while others are leased by dealers who sell only one brand of gas.

There are supposedly nine benefits to being a branded lessee-dealer:

(1) a wider variety of grades of gasoline than unbranded, which leads to higher gross profit margins,

(2) access to oil company credit card at no fee,

(3) oil company third party fee discount for VISA and MasterCard,

(4) “subsidies” in the form of soft loans and investments,

(5) marketing assistance,

(6) rebates based on incremental volume,

(7) training and support on how to run a profitable gasoline station,

(8) technical support and station startup design, and

(9) security of supply.

There are also open dealers, who sign contracts with a particular brand, but can shift their allegiance whenever the contract expires. Open dealers interface with refiners through middlemen known as jobbers. A jobber will often supply several dealers, and depending on the size of the operation, will sign contracts, or buy unbranded gas either from the rack or the spot market.

Finally, there are the true independents. These folks shop around for the best unbranded gas price, sometimes aided by a jobber. They almost never sign long term contracts and almost always get their gas from the rack or the spot market.

At the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. had just under 175,000 gas stations. Of those, about 55,000 are run by independent operators. Of the remainder, half are run by open dealers, and the other half is split between company-owned and lessee-dealer stations.

Fixing The Price Of Gas

Oil companies set the price of gas at company-owned stations. What they say, goes. With lessee-dealers, the relationship is more complex.

Lessee-dealers are charged a ‘Dealer Tank Wagon’ (DTW) price by the oil companies. The DTW price is set either by the oil company’s central or regional office, and is driven by both the spot and futures markets. Most importantly, oil companies determine the DTW price by looking at the prices of other stations in the market. This is why two stations with the same brand a block away from each other can have different prices.

Lessee-dealers can’t negotiate a DTW price since they sign contracts with just one oil company that require them to purchase a minimum amount of gas. Oil companies allow dealers to sell gas at a slightly inflated margin to ensure a profit stream so the dealers can put food on their family’s table. That margin can range from 3-10 cents per gallon.

Why don’t dealers just raise the prices more, like 20 cents a gallon, so they can give their families even more food? Some do. If they’re caught, you can bet anything the next DTW price will be higher, bringing their profit margins back to normal – only now, their gas is more expensive than their neighboring stations and they have a competitive disadvantage.

DTW pricing is the product of an exceedingly complex and secretive pricing scheme known as zone pricing. A zone can be as small as a single gas station, or as large as a city. The testimony of a Mobil representative in 1997 revealed that Mobil had 46 zones in Connecticut. Most dealers have no idea what zone they are in, even though the DTW price given to their neighboring stations can determine their standing in a local market.

Oil companies, like politicians reapportioning voting districts, rely heavily on technology to slice apart local markets. The DTW price in each zone will be different, taking account several factors including nearby competition, demographics, and the historical demand of the zone. Oil companies also seek to determine the price elasticity of each zone, or how much the zone will pay for gas before looking for alternative suppliers. For some zones, that breaking point is a penny, for others, it two or three cents, and some will stay with their station out of a sense of loyalty. These factors can cause the price of gas in neighboring zones to fluctuate by as much as a dime.

Oil companies adjust zone price by considering what their competitors are doing. The price of rival gas stations will be surveyed two or three times a week, or the data will be relayed to the oil companies by refiners.

Taxes

State and federal taxes account for about 18% of the price of gas. The cost is a constant and is factored into the baseline price of gas.

Eliminating those taxes would reduce the price of gas by a few cents, but would do nothing to otherwise address the underlying factors involved in pricing gas.

Ok… so why IS gas so expensive?

A butterfly flaps its wings in the Saudi desert, causing the State Department to release a warning of increased terrorist activity. The futures market flips out, sending the price of crude skyward. The higher price on the futures market makes it more expensive for refiners to acquire crude to refine into gas. When the refiner’s work is done, the emerging gas will be priced accordingly higher. This raises the rack price and the prices on the spot markets. Oil companies and jobbers with long-term contracts might be insulated from the higher price, depending on their contracts. Refining oil into gas isn’t instantaneous, and there can be a lag before the higher price of the oil is reflected in higher gas prices paid by jobbers and oil companies. That, of course, didn’t stop them from raising prices the moment the futures market jumped. So now that the oil that was purchased for refining at a higher cost is ready to hit the market as gas, the oil companies will raise prices again. This double-dipped price is passed onto dealers as the DTW price, which is then inflated yet again so the dealers can turn a profit. You paid more for gas thanks to a butterfly. “It’s just a !@$% butterfly!,” you say. Sure, but it scared the hell out of the markets. Since the oil companies all move in lockstep, that butterfly can cause the price of gas to rise for several days as one oil company sees another raising prices and adjusts accordingly. Eventually the markets will calm and the price will begin to fall. This allows the introduction of a friend much more insidious than the butterfly: price gouging. Despite popular misconceptions, price gouging almost never occurs as prices rise. Instead, price gouging occurs when dealers keep prices artificially high in order to gain a little extra profit or recoup costs, even though the DTW price has declined. Sticking with our butterfly friend, let’s say she caused the DTW price of gas to spike for four days. It may be ten days before dealers lower their prices. That’s price gouging. Most people never notice true price gouging. They will complain that the price went too high, but that’s the fault of the oil companies, not the dealers. Prices that stay high for too long go unnoticed. Just because the price of gas stays high does not mean that a dealer is price gouging. The price may actually be higher. That’s why it’s almost impossible to prove, let alone prosecute, price gouging. Conclusion Unless you’re a Saudi Arabian butterfly, you can’t hope to control the oil market, but you can control your consumption. Reduce your gas costs by carpooling, biking, walking, using gas price finder sites to decrease the information asymmetry, and/or switching to a car with a better MPG. RELATED: (Photo: Getty)

Most of the above draws on the excellent work of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, which produced a 324 page report that makes for a fascinating read. Direct links to the report sections are below:

Executive Summary

Introduction

The Production and Marketing of Gasoline

The Effects Of Market Structure And Concentration On Gasoline Prices

How Gasoline Prices Are Set

What Goes Into The Price Of Gas?

Get 30 More Miles Per Tank: Turn Off Engine If Idling More Than 10 Seconds

Potentially Insane Ways To Increase Your Fuel Efficiency

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published May 2007. I decided to republish it now because it’s one of my favorite posts Carey ever did, and it’s incredibly relevant in the current economic situation.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.