Despite Regulations Most Consumers Don’t Understand Overdraft Penalty Plans; More Rules Needed

Since 2010, financial institutions have been required to obtain an opt-in confirmation from consumers before enrolling them in overdraft penalty plans, yet a new report found more than 50% of consumers who incurred such penalty fees in the past year don’t believe they opted into any such plans. This revelation, coupled with consumers’ concerns over fees and bank practices, has led to a call for federal regulators to improve rules governing financial institutions’ overdraft policies.

The Pew Charitable Trusts report [PDF], an expansion of a 2012 survey that focused solely on overdrafters, found consumers’ understanding of such programs has not improved in the last year and that concerns remain in regards to fee costs and bank practices.

“Checking accounts are the most widely used financial product in the country, yet many consumers are still concerned and puzzled by bank overdraft practices,” Susan Weinstock, who directs Pew’s consumer banking research, says. “Overdraft protections shouldn’t be a guessing game. We urge the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to write new rules to make overdraft programs safer and more transparent.”

THE MANY FACES OF OVERDRAFTS

Consumers generally have three choices when it comes to not having enough funds to cover a debt card purchased or ATM withdrawal:

•Incur an overdraft penalty fee – the consumers bank makes a short-term advance to cover the transaction and charges a fee for the service. The median fee for this option is $35.

•Incur an overdraft transfer fee – the bank transfers funds from a linked source, such as a savings account, line of credit or credit card, and charges a fee for the service. The median fee charged is $10.

•Have the transaction declined – if the consumer did not opt for one of the above options, the transaction is denied and no fee is charged.

The survey also included a group called “never-negatives”; people who never completed a debit card transaction that would have resulted in a negative account balance or had a transaction declined for insufficient funds.

Pew found that younger, lower-income, and nonwhite consumers without credit cards were among those who were most likely to fall into the first category.

WHAT OVERDRAFTING LOOKED LIKE IN 2013

According to the report, nearly 10% of Americans paid at least one overdraft penalty in 2013, and an additional 5% of consumers paid an overdraft transfer fee.

However, 68% of survey respondents who received an overdraft penalty say they would prefer that their transaction was declined rather than pay an overdraft fee of any kind.

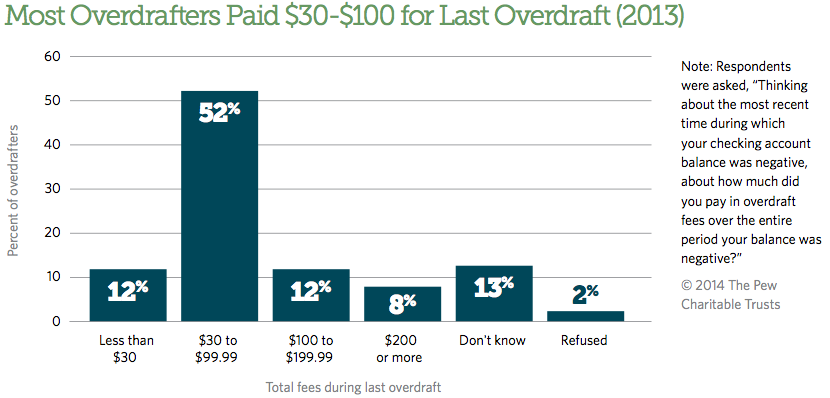

On average, consumers reported paying $69 in fees during their most recent overdraft event. Although the median overdraft fee was $35, a quarter of overdrafters reported paying $90 or more because their negative balance resulted in additional penalty fees.

Seventy percent of those who overdrafted reported that their account was negative for four or fewer days, while nearly 31% regained a positive balance the same day.

In 2012, U.S. consumers paid $32 billion in overdraft penalties. Research has shown that such fees can push consumers out of the banking system. In fact, nearly 28% of overdrafters say they closed their checking account in the past. An additional 19% of consumers inquired about discontinuing their participation in plans.

REORDERING TRANSACTIONS

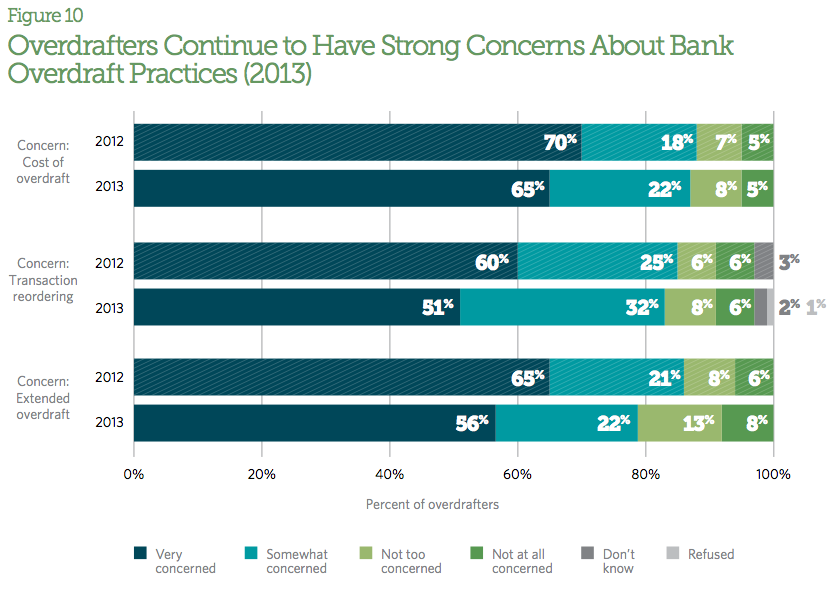

Another chief concern consumers reported regarding overdraft policies was the practice of banks to reordering transactions from highest to lowest to maximize fees. This practice only inflates the issue of overdrafting and in the end consumers pay significantly more.

Pew reports that while banks have employed additional policies that can help limit the impact of overdraft fees, including reordering only certain types of transactions, implementing a threshold amount to trigger an overdraft, and not charging an extended overdraft fee, more attention is needed for this often unfair practice.

UNCLEAR DISCLOSURES

While it appears many consumers have plenty of experience with overdraft penalties, the majority report being confused by terms and fees of such plans.

Pew reports that because so many consumers don’t remember or incorrectly recall opting in a overdraft plan, that there is significant doubt on the clarity of current disclosures and the manner in which such plans are marketed to consumers.

Back in April another Pew report found that disclosures were significantly lacking in many of the countries largest banks.

Many of the banks evaluated in that report made important progress when it came to disclosure practices including adopting a Pew approved disclosure box, but none of the banks scored “good” or “best” practices.

THE NEED FOR MORE REGULATION

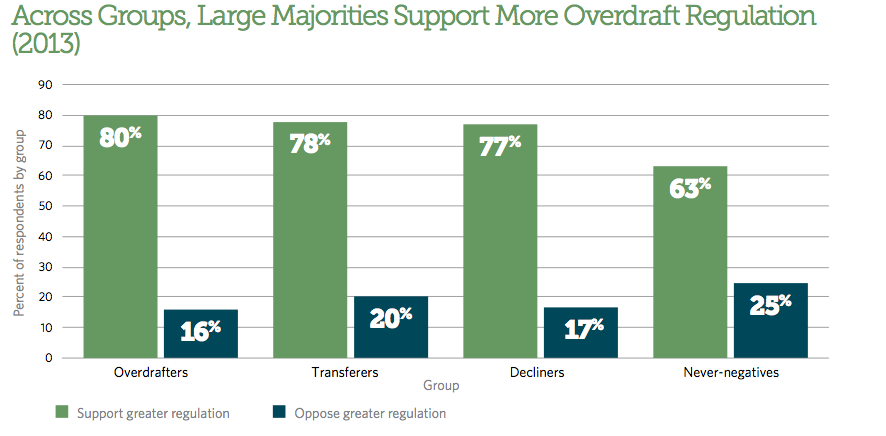

Additionally, large portions of consumers, both overdrafters and those who have never overdrafted, would support regulations that would oversee overdraft fees and practices.

To prevent checking account overdraft fees from leading to financial distress for consumers, Pew suggests that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau use its power to better regulate such plans by:

- Provide account holders with clear, comprehensive, and uniform pricing information for all available overdraft options.

- Make overdraft penalty fees reasonable and proportional to the bank’s costs in covering the overdraft.

- Stop the practice of reordering transactions to maximize fees, and post deposits and withdrawals in a fully disclosed, objective, and neutral manner.

“Terms need to be fair to consumers and not confusing,” Weinstock says. “The CFPB has power to make these changes.”

Overdrawn: Persistent Confusion and Concern About Bank Overdraft Practices [Pew Charitable Trust]

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.