The Nigerian Prince E-Mail Scam Is Actually 200 Years Old

E-mail is an invention of the last few decades, but scamming people? That’s an ancient calling. What you may not know when you toss those advance fee scam e-mails into your spam folder is that the senders are taking part in an old, old scam that dates back to the early 19th century.

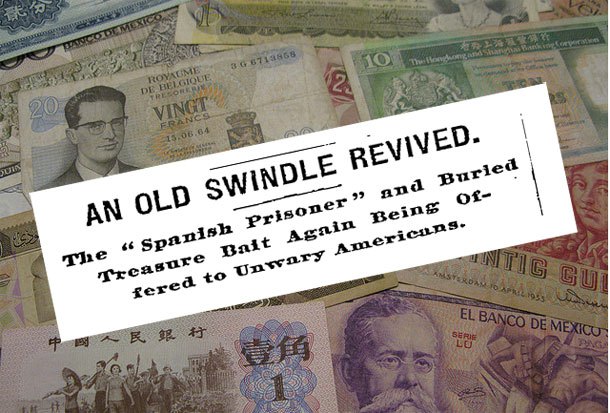

No, really. There’s a fantastic piece in The Appendix, one of the least boring history journals ever, about the history of the Spanish Prisoner scam. The New York Times was calling it “an old swindle” in 1898. The scam came to be known as the “Spanish Prisoner Letter.” Back in the Victorian era, Spain had some of the same reputation for criminal sketchiness as Nigeria does now….at least to people in the United Kingdom. Wars provided a useful and plausible backdrop.

Just because you don’t have mass e-mail capabilities, that doesn’t mean you can’t blast messages out to strangers. It just takes a lot longer. The very earliest letters were hand-written. That means the fraudsters would have to use more finesse when crafting the letter and send along a bunch of evidence.

As far as we know, the scam dates back to the Peninsular War (1807-1814) fought over the Iberian peninsula. Some of the details changed depending on the date and political situation, but civil wars in Spain always provided an excitingly dangerous backdrop.

The broad strokes will sound familiar to anyone with an e-mail account. In one 1905 example now in the hands of the UK’s Metropolitan police. The letter-writer is a Spaniard who once had a high-ranking military job and is now out of favor. He fled to England, but returned when his wife died in order to care for his teenage daughter. Now he’s dying of hepatitis in prison, and needs the letter recipient’s help. If he could just free his daughter and his luggage from the Spanish authorities, his bank account details are concealed there and he could get his money back…which, of course, he would share with the letter’s recipient.. Could he send just 59 pounds in return for a share of the fortune and guardianship of the young heiress when her father dies, which will be any minute now?

Like modern advance fee schemes, the goal is to prey on the recipient’s sentimentality and his greed. There’s even a fake intermediary: a prison chaplain with whom the mark exchanges cables and letters. Everyone involved warned the recipient not to go to the authorities, or the girl would be in danger.

When the poor prisoner “died,” his chaplain go-between sent along his death certificate, newspaper clippings, and other official-looking documents. Unfortunately, while juggling too many correspondences, the scammer mixed a few up, addressing a letter to one mark’s name at another man’s address. This man turned everything over to the police, which is why we have them today.

Advances in scam technology came when ordinary people started to own typewriters, speeding up letter production considerably. The publication of Who’s Who, a volume that provided information about the country’s most prominent citizens, made finding potential victims with money even easier. No more sending letters to men who had been dead for years, as the scammers had done in the past.

While the letters appeared to come from Spain, experts believe that most of them really originated in England. When the number of attempted scams surged in the early 20th century, the police placed notices in post offices: not enough to save everybody, but at least to save a few people. Few perpetrators were ever caught.

Click through the article: you can see the original letters, the fake documents, and more tales of antique scams.

Proto-Spam: Spanish Prisoners and Confidence Games [The Appendix] (via On The Media)

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.