3 Things We’ve Learned About How Demographics, Credit Scores & Marital Status Affect Your Car Insurance Rates

When you get a quote for car insurance, you might think that only a few things matter — your driving record, the cost and use of your vehicle, the type of coverage you need, and other factors directly related to operating an automobile. But the fact is that many insurers are basing your insurance quotes on data points that have nothing to do with driving, like your credit score, marital status, and ZIP code. New research shows that determining price using these types of demographic and financial factors (rather than driving record alone) can have a serious impact on the affordability of car insurance.

While some states have restrictions on the use of things like credit scores in setting an auto insurance premium, only California has a law requiring insurers to offer drivers with clean driving records the lowest premium for which they qualify.

Recent reports from the Consumer Federation of America, and our colleagues at Consumers Union and Consumer Reports have tried to spotlight the various ways in which auto insurers use these unrelated — or at best tangentially related — bits of information to determine how much people will pay for coverage.

Since reading about insurance can be a slog, we’ve tried to boil down some of the most important discoveries to come out of this research.

1. Drivers in predominantly African-American ZIP codes tend to pay more than those living in areas with mostly white residents

This is the conclusion of a report released today by the Consumer Federation of America, which compared quotes from the nation’s five largest insurers to see what effect, if any, the use of non-driving factors had on the price of auto insurance in predominately African-American communities. As we explore the findings of the report, it’s important to note that the analysis did not attempt to prove that auto insurance companies were intentionally raising prices for consumers who live in predominately African-American ZIP codes. The CFA’s research addresses the impact of auto insurance pricing methodologies on these communities, and provides compelling evidence that the current methods of pricing of auto insurance result in good drivers in predominantly African-American communities paying higher prices than similarly situated drivers in predominantly white communities, even when controlling for factors such as urban-density and income.

The same fictional driver profile — 30-year-old single female with a clean driving record, no lapses in coverage, steady employment, a rental apartment, and a “Fair” credit rating, driving a 2000 Honda Civic around 10,000 miles a year — was used to obtain quotes from the insurers in all of the areas included in the survey.

Researchers looked at insurance premiums for this fictional driver in a variety of environments — urban to rural — and across average income levels of area residents, from below $20,000 a year to more than $100,000 annually.

According to the report, “on average, a good driver in a predominantly African-American community will pay considerably more for state-mandated auto insurance coverage than a similarly situated driver in a predominantly white community.”

More precisely, researchers found that when a neighborhood’s racial makeup is at least 75% African-American, car insurance premiums average 70% higher than those quoted for the same driver living someplace where the African-American population is below 25%. For the fictional driver in the study, that means a difference of more than $400 per year ($1,060, compared to $622).

Even at lower concentrations of African-American residents, the average premiums are still significantly more expensive. That same driver would face an average rate of $831 (a 34% difference) if she lived in a community that was between half and three-quarters African-American. The average premium drops to $768 when white residents account for half to three-quarters of the population. That’s still around 24% higher than people pay in predominantly white ZIP codes.

On average, drivers living in predominantly African-American ZIP codes see premiums that are 70% higher than prices in predominantly white areas.

Consumer Federation of America

These are all national averages, and include both rural and urban communities. To get a more accurate comparison, CFA also looked at drivers in similarly dense ZIP codes — and once again found disparities.

In the densest urban communities — where premiums are typically high because of traffic, crime, and potential for damage — the average premium ($1,797) in predominantly African-American ZIP codes is 60% percent higher than in dense urban areas populated primarily by white residents ($1,126); a difference of more than $600.

The gap isn’t as distinct in rural ZIP codes, where predominantly white communities see an average of $542 for their insurance premiums, 23% less than the $669 average found in predominantly African-American rural areas.

The biggest difference in insurance premiums was found when CFA researchers compared upper middle-income drivers. In predominantly white ZIP codes where the average annual income was between $63,000 to $102,000, insurance premiums averaged $717. Compare that to the same income range for predominantly African-American ZIP codes, where the average premium clocked in at $2,113 — an increase of 194%, nearly triple the cost to the driver.

And since having a car is not optional for most working adults — and having insurance is required everywhere but New Hampshire — CFA’s research suggests that some people earning a decent living are effectively being compelled to pay an additional $1,400 a year despite having a clean driving record.

Progressive & Farmers charge drivers in African-American neighborhoods rates nearly double their premiums for drivers in mostly white ZIP codes.

Of the five insurance companies included in the report, Progressive and Farmers demonstrated the most obvious gulf between rates in predominantly white and predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Both companies quoted rates for drivers living in mostly African-American communities that were nearly double the average premium for the same driver in ZIP codes where white residents account for at least three-quarters of the population (Progressive: $1,332 vs. $694; Farmers: $1,271 vs. $662).

GEICO had the lowest average rates of the five (predominantly white: $575; predominantly African-American: $876), but that’s still a difference of 53% for — not to beat this horse to death — the same driver profile.

The CFA says the goal of this report is not to claim that insurers are intentionally charging more in non-white communities.

“We believe, instead, that it would be more productive to focus on the impact of high auto insurance prices and the implications these findings should have for industry, regulators, and policymakers,” reads the report.

As a result of their research, the CFA is calling on state legislators and insurance regulators to, among other things, require that all insurers provide a pricing report showing the premium for a standardized, safe driver in every ZIP code in the state.

Ideally, the report would also include demographic information about each ZIP code, as that added transparency would effectively require insurers to explain why certain communities are paying more or less than others.

2. Convicted drunk drivers with good credit might have better premiums than good drivers with poor credit

You can understand why a poor credit history would result in higher auto loan rates. But what does your failure to make a student loan payment seven years ago, or an unexpectedly huge medical bill you couldn’t pay right away, have to do with the likelihood that you’ll get into an accident?

It’s not like the insurance companies aren’t checking your driving history; if you have a clean driving record, it shouldn’t matter whether your FICO score is 600 or 800.

And yet in all but three states — California, Hawaii, and Massachusetts — insurers are allowed to use your creditworthiness to determine your insurance premium.

Earlier this year, Consumer Reports found that credit scores can have more effect on your insurance rates than any other factor.

In some states, drivers with moving violations on their record could end up paying less than drivers with clean records, solely because of a difference in credit scores.

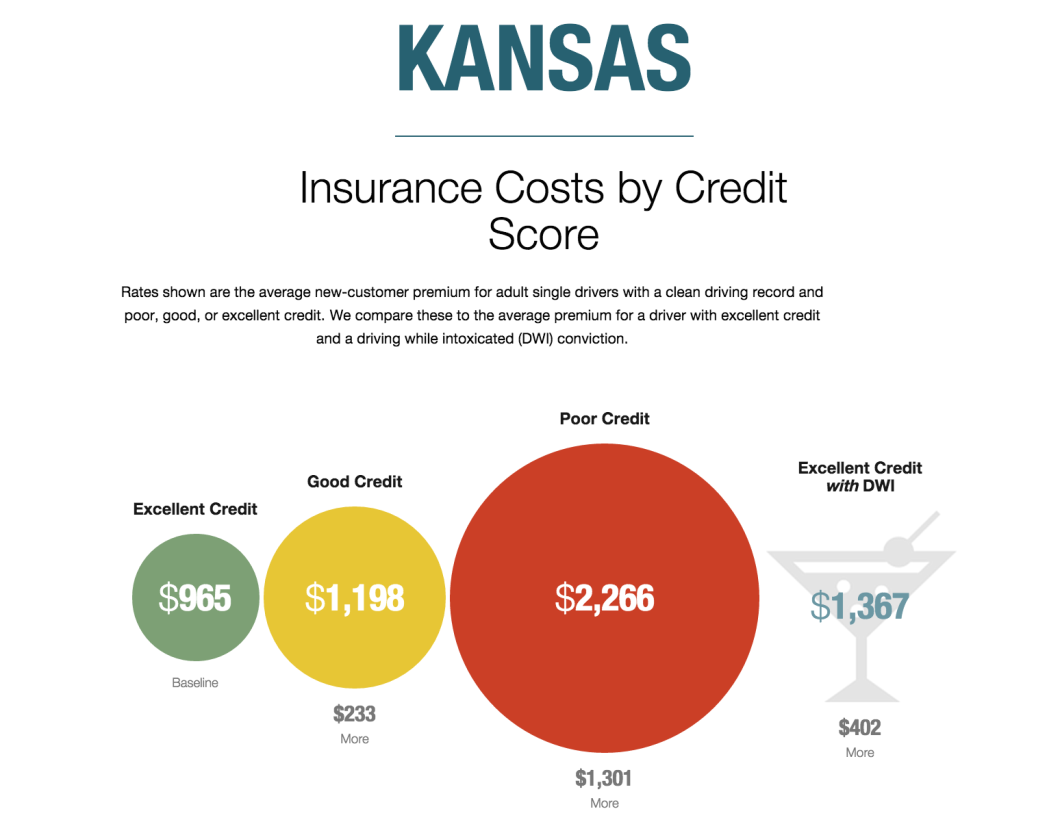

See the chart below for an example. According to CR’s research (also using fictional, standardized driver profiles), drivers in Kansas with “Excellent” credit and a pristine driving record average $965 a year in car premiums. Merely having “Good” credit raises that average by $233 a year. If a Kansan has “Poor” credit, their insurance could soar to $2,266/year, nearly 2.5 times the rate for someone with credit.

More importantly, it’s almost $1,000 more than the average premium seen by a driver with a drunk driving conviction. So insurers in this case are saying that someone with bad credit is more of an insurance risk than someone whose record shows they willingly risked their lives and others’ by driving while intoxicated.

“From a public safety perspective, this makes no sense,” explains Norma Garcia, senior attorney at Consumers Union.

Tomorrow, Garcia will be testifying before the National Association of Insurance Commissioners about the mysterious world of insurance rates, where she intends to raise the issue of penalizing a driver with poor credit more than one with a DWI conviction.

“According to the most recently available statistics from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, there were over 11,000 known blood alcohol content related driver deaths in 2013,” notes Garcia in her prepared remarks. “No doubt, the hazards of drunk driving are painfully real. By contrast, despite the negative view of drivers with poor credit held by many insurance companies, we are not aware of any traffic fatalities attributable to poor credit, yet in many cases, these drivers continue to pay more than the most hazardous drivers on the road.”

3. Unmarried and widowed drivers sometimes pay more than than married folks

In July, the CFA released a report on how marital status impacts car insurance rates. Of the six insurers included in the study, only one — State Farm — showed no variation in rates between single drivers and married ones.

The other insurers — GEICO, Farmers, Progressive, Nationwide, and Liberty — have no such blanket policy with regard to marital status, and single drivers often pay more.

In many parts of the country, singles paid these insurers more than their married counterparts, with the range of rate increases ranging wildly from 0% to more than 200%.

Age didn’t matter, says CFA. The range of price hikes for their fictional 30-year-old single driver were effectively the same when they obtained quotes for a 50-year-old.

What does seem to matter is location. Researchers looked at rates in 10 different markets around the country and found that the insurers were inconsistent in their application of these pricing differences.

For example, in Boston, Farmers quoted rates 12.5% higher for singles than married customers. But in Tampa, the insurer charges single drivers nearly 34% more than married drivers in that market. Then in California, where marital status is only allowed as a low-impact “optional” factor in setting prices, Farmers charges the exact same price regardless of whether or not you’ve ever been married.

While the other insurers made no distinction between single, divorced, and widowed drivers, GEICO bucked this trend by sometimes charging varying amounts for all the different ways in which a driver can be single.

“Hiking rates on women whose husbands die seems both unfair and inhumane.”

Stephen Brobeck

In Louisville, for example, GEICO charges five different rates in six different categories, with “separated” drivers paying the most (nearly triple the premium for married drivers), but divorced drivers seeing the smallest difference (though still almost double the base married rate).

While one could try to argue that being single — even by divorce — is a matter of choice that might reflect on a driver’s likelihood to take risks, what seems indefensible is the higher premiums some insurers charge to widows.

CFA researchers made their young driver a widow, and saw her rates quotes go up by an average of 14%.

“Hiking rates on women whose husbands die seems both unfair and inhumane,” said Stephen Brobeck, CFA’s Executive Director, at the time of the study. “Why don’t insurers instead emphasize driving-related factors such as accidents, traffic violations, and miles driven in their pricing?”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.