How Safe Is Your Ground Beef? Image courtesy of Consumer Reports

This story was first published by our sister publication Consumer Reports.

The American love affair with ground beef endures. We put it between buns. Tuck it inside burritos. Stir it into chili. Even as U.S. red meat consumption has dropped overall in recent years, we still bought 4.6 billion pounds of beef in grocery and big-box stores over the past year. And more of the beef we buy today is in the ground form—about 50 percent vs. 42 percent a decade ago. We like its convenience, and often its price.

The appetite persists despite solid evidence—including new test results here at Consumer Reports—that ground beef can make you seriously sick, particularly when it’s cooked at rare or medium-rare temperatures under 160° F. “Up to 28 percent of Americans eat ground beef that’s raw or undercooked,” says Hannah Gould, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

All meat potentially contains bacteria that—if not destroyed by proper cooking—can cause food poisoning, but some meats are more risky than others. Beef, and especially ground beef, has a combination of qualities that can make it particularly problematic—and the consequences of eating tainted beef can be severe.

Indeed, food poisoning outbreaks and recalls of bacteria-tainted ground beef are all too frequent. Just before the July 4 holiday this year, 13.5 tons of ground beef and steak destined for restaurants and other food-service operations were recalled on a single day because of possible contamination with a dangerous bacteria known as E. coli O157:H7. That particular bacterial strain can release a toxin that damages the lining of the intestine, often leading to abdominal cramps, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and in some cases, life-threatening kidney damage. Though the contaminated meat was discovered by the meat-packing company’s inspectors before any cases of food poisoning were reported, we haven’t always been so lucky.

Between 2003 and 2012, there were almost 80 outbreaks of E. coli O157 due to tainted beef, sickening 1,144 people, putting 316 in the hospital, and killing five. Ground beef was the source of the majority of those outbreaks. And incidences of food poisoning are vastly underreported. “For every case of E. coli O157 that we hear about, we estimate that another 26 cases actually occur,” Gould says. She also reports that beef is the fourth most common cause of salmonella outbreaks—one of the most common foodborne illnesses in the U.S.—and for each reported illness caused by that bacteria, an estimated 29 other people are infected.

The risks of going rare

It’s not surprising to find bacteria on favorite foods such as chicken, turkey, and pork. But we usually choose to consume those meats well-cooked, which makes them safer to eat. Americans, however, often prefer their beef on the rare side. Undercooking steaks may increase your risk of food poisoning, but ground beef is more problematic. Bacteria can get on the meat during slaughter or processing. In whole cuts such as steak or roasts, the bacteria tend to stay on the surface, so when you cook them, the outside is likely to get hot enough to kill any bugs. But when beef is ground up, the bacteria get mixed throughout, contaminating all of the meat—including what’s in the middle of your hamburger.

Also contributing to ground beef’s bacteria level: The meat and fat trimmings often come from multiple animals, so meat from a single contaminated cow can end up in many packages of ground beef. Ground beef (like other ground meats) can also go through several grinding steps at processing plants and in stores, providing more opportunities for cross-contamination to occur. And then there’s the way home cooks handle raw ground beef: kneading it with bare hands to form burger patties or a meatloaf. Unless you’re scrupulous about washing your hands thoroughly afterward, bacteria can remain and contaminate everything you touch—from the surfaces in your kitchen to other foods you are preparing.

“There’s no way to tell by looking at a package of meat or smelling it whether it has harmful bacteria or not,” says Urvashi Rangan, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Food Safety and Sustainability at Consumer Reports. “You have to be on guard every time.” That means keeping any raw meat on your countertop from touching other foods nearby and cooking ground beef to at least medium, which is 160° F. Eating a burger that’s rarer can be risky. In one 2014 E. coli outbreak, five of the 12 people who got sick had eaten a burger at one of the locations of an Ohio pub chain called Bar 145°, which was named for the temperature “of a perfectly cooked medium-rare burger,” according to the company’s website.

RELATED: How to cook a burger to a safe temperature that’s still tasty

Putting beef to the test

Given those concerns about the safety of ground beef, Consumer Reports decided to test for the prevalence and types of bacteria in ground beef. We purchased 300 packages—a total of 458 pounds (the equivalent of 1,832 quarter-pounders)—from 103 grocery, big-box, and natural food stores in 26 cities across the country. We bought all types of ground beef: conventional—the most common type of beef sold, in which cattle are typically fattened up with grain and soy in feedlots and fed antibiotics and other drugs to promote growth and prevent disease—as well as beef that was raised in more sustainable ways, which have important implications for food safety and animal welfare. At a minimum, sustainably produced beef was raised without antibiotics. Even better are organic and grass-fed methods. Organic cattle are not given antibiotics or other drugs, and they are fed organic feed. Grass-fed cattle usually don’t get antibiotics, and they spend their lives on pasture, not feedlots.

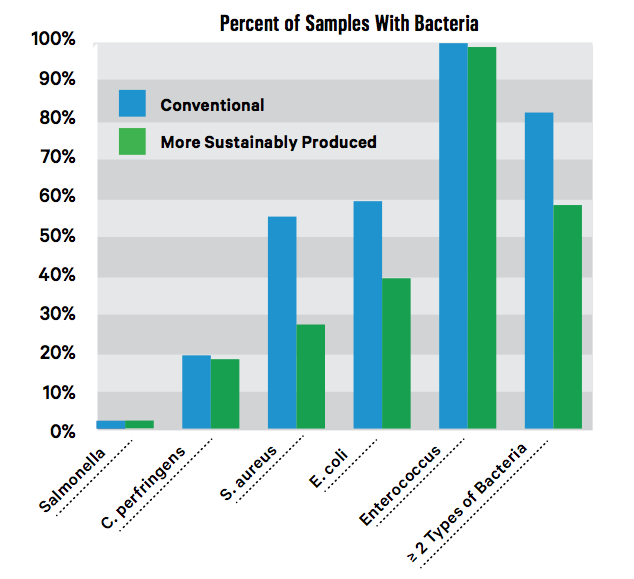

We analyzed the samples for five common types of bacteria found on beef—clostridium perfringens, E. coli (including O157 and six other toxin-producing strains), enterococcus, salmonella, and staphylococcus aureus.

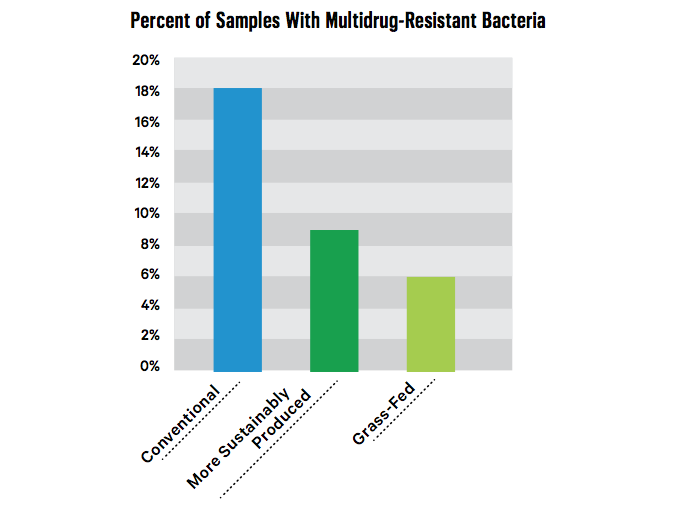

The routine use of antibiotics in farming has contributed to the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, so once-easy-to-treat infections are becoming more serious and even deadly. We put the bacteria we found through an additional round of testing to see whether they were resistant to antibiotics in the same classes that are commonly used to treat infections in people. Last, we compared the results of samples from conventionally raised beef with the sustainably raised beef to see whether there were differences in the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria between the products.

The results were sobering. All 458 pounds of beef we examined contained bacteria that signified fecal contamination (enterococcus and/or nontoxin-producing E. coli), which can cause blood or urinary tract infections. Almost 20 percent contained C. perfringens, a bacteria that causes almost 1 million cases of food poisoning annually. Ten percent of the samples had a strain of S. aureus bacteria that can produce a toxin that can make you sick. That toxin can’t be destroyed—even with proper cooking.

Just 1 percent of our samples contained salmonella. That may not sound worrisome, but, says Rangan, “extrapolate that to the billions of pounds of ground beef we eat every year, and that’s a lot of burgers with the potential to make you sick.” Indeed, salmonella causes an estimated 1.2 million illnesses and 450 deaths in the U.S. each year.

One of the most significant findings of our research is that beef from conventionally raised cows was more likely to have bacteria overall, as well as bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics, than beef from sustainably raised cows. We found a type of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus bacteria called MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus), which kills about 11,000 people in the U.S. every year, on three conventional samples (and none on sustainable samples). And 18 percent of conventional beef samples were contaminated with superbugs—the dangerous bacteria that are resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics—compared with just 9 percent of beef from samples that were sustainably produced. “We know that sustainable methods are better for the environment and more humane to animals. But our tests also show that these methods can produce ground beef that poses fewer public health risks,” Rangan says.

The majority of beef (about 97 percent) for sale comes from “conventionally raised” cattle that begin their lives grazing in grassy pastures but are then shipped to and packed into feedlots and fed mostly corn and soybeans for three months to almost a year. The animals may also be given antibiotics and hormones. That practice is considered to be the most cost-efficient way to fatten up cattle: It takes less time, labor, and land for conventionally raised cattle to reach their slaughter weight compared with those that feed on grass their whole lives. “The high-carbohydrate corn and soy diet causes cattle to become unnaturally obese creatures that would never exist in nature,” says farmer Will Harris, who decided 20 years ago to switch to raising grass-fed cattle at White Oak Pastures, his 2,500-acre fifth-generation family farm in Bluffton, Ga. “Conventional cattle reach 1,200-plus pounds in 16 to 18 months. On our farm, it takes 20 to 22 months to raise an 1,100-pound animal, which is what we consider slaughter weight.”

RELATED: 5 Ground Beef Labels To Look Out For & What They Mean

Cows’ digestive systems aren’t designed to easily process high-starch foods such as corn and soy. Cattle will gain weight faster on a grain-based diet than on a grass-based one. But it also creates an acidic environment in the cows’ digestive tract, which can lead to ulcers and infection. Research shows that this unnatural diet may also cause the cattle to shed more E. coli in their manure. In addition, cattle may be fed a variety of other substances to fatten them up. They include candy (such as gummy bears, lemon drops, and chocolate) to boost their sugar intake and plastic pellets to substitute for the fiber they would otherwise get from grass. Cattle feed can also contain parts of slaughtered hogs and chickens that are not used in food production, and dried manure and litter from chicken barns.

Conventional cattle farmers defend their methods, however. “If all cattle were grass-fed, we’d have less beef, and it would be less affordable,” says Mike Apley, Ph.D., a veterinarian, professor at Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine, and chair of the Antibiotic Resistance Working Group at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a trade group. “Since grass doesn’t grow on pasture year-round in many parts of the country,” he says, “feedlots evolved to make the most efficient use of land, water, fuel, labor, and feed.”

Cows: They are what they eat

Image courtesy of Consumer ReportsThe majority of beef (about 97 percent) for sale comes from “conventionally raised” cattle that begin their lives grazing in grassy pastures but are then shipped to and packed into feedlots and fed mostly corn and soybeans for three months to almost a year. The animals may also be given antibiotics and hormones. That practice is considered to be the most cost-efficient way to fatten up cattle: It takes less time, labor, and land for conventionally raised cattle to reach their slaughter weight compared with those that feed on grass their whole lives. “The high-carbohydrate corn and soy diet causes cattle to become unnaturally obese creatures that would never exist in nature,” says farmer Will Harris, who decided 20 years ago to switch to raising grass-fed cattle at White Oak Pastures, his 2,500-acre fifth-generation family farm in Bluffton, Ga. “Conventional cattle reach 1,200-plus pounds in 16 to 18 months. On our farm, it takes 20 to 22 months to raise an 1,100-pound animal, which is what we consider slaughter weight.”

Cows’ digestive systems aren’t designed to easily process high-starch foods such as corn and soy. Cattle will gain weight faster on a grain-based diet than on a grass-based one. But it also creates an acidic environment in the cows’ digestive tract, which can lead to ulcers and infection. Research shows that this unnatural diet may also cause the cattle to shed more E. coli in their manure. In addition, cattle may be fed a variety of other substances to fatten them up. They include candy (such as gummy bears, lemon drops, and chocolate) to boost their sugar intake and plastic pellets to substitute for the fiber they would otherwise get from grass. Cattle feed can also contain parts of slaughtered hogs and chickens that are not used in food production, and dried manure and litter from chicken barns.

Conventional cattle farmers defend their methods, however. “If all cattle were grass-fed, we’d have less beef, and it would be less affordable,” says Mike Apley, Ph.D., a veterinarian, professor at Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine, and chair of the Antibiotic Resistance Working Group at the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a trade group. “Since grass doesn’t grow on pasture year-round in many parts of the country,” he says, “feedlots evolved to make the most efficient use of land, water, fuel, labor, and feed.”

Life on the feedlot

Farmers such as Will Harris are also concerned about the humaneness of crowding cows into feedlots. “Animals that have never been off grass are put into a two-story truck and transported for 20-plus hours with no food, water, or rest,” Harris says. The animals are crowded into pens; the average feedlot in the U.S. houses about 4,300 head of cattle, according to Food & Water Watch’s 2015 Factory Farm Nation Report. On some of the country’s biggest feedlots, the cattle population averages 18,000.

“You always know when you’re approaching a feedlot. The unmistakable stench hits you first, then you see the hovering fecal dust cloud, followed by the sight of thousands of cattle packed into pens standing in their own waste as far as you can see,” says Don Davis, a cattle farmer in Texas and president of the Grassfed Livestock Alliance. The manure contains potentially dangerous bacteria that gets on the cattle’s hides and can be transferred to the meat during slaughter. The conditions also stress the cattle, which makes them more susceptible to disease, and any illness that develops can quickly spread from animal to animal.

To control for that, cattle are often fed daily low doses of antibiotics to prevent disease. According to Apley, cattle in feedlots are given antibiotics to prevent coccidiosis, a common intestinal infection, but he notes that those drugs aren’t medically important for people. He also said that cattle are given an antibiotic called tylosin to ward off liver abscesses. That drug is in a class of antibiotics that the World Health Organization categorizes as “critically important” for human medicine. What’s more, in our tests we found that resistance to classes of antibiotics used to treat people was widespread. Three-quarters of the samples contained bacteria that were immune to at least one class of those drugs.

Antibiotics were also given to cattle to promote weight gain (although just how the drugs do that is unknown), but in 2013 the Food and Drug Administration issued voluntary guidelines to stop that practice. Previously, ranchers could buy those drugs over-the-counter and give them to their animals, but the FDA has proposed that antibiotics be used only under the supervision of a veterinarian. “That doesn’t mean, though, that antibiotics can’t be used for disease prevention anymore,” says Jean Halloran, director of Food Policy Initiatives at Consumer Reports. “Vets can still authorize their use to ‘ensure animal health,’ so the status quo of feeding healthy animals antibiotics every day can continue.” Widespread daily and unnecessary use of antibiotics in healthy animals in turn fuels the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which has become a serious public-health threat.

Meat monopoly

More than 80 percent of beef produced in the U.S. is processed by four companies. Cattle can be slaughtered at high-speed rates—as many as 400 head per hour. Those slaughterhouses use a variety of methods to destroy bacteria on the carcass after the hide has been removed, such as hot water, chlorine-based, or lactic acid washes. But when so many cattle are being processed, sanitary practices may get short shrift. The result is that bacteria from cattle’s hides or digestive tracts can be transferred to the meat. “USDA has a presence in these plants to do inspections—though it’s against the companies’ wishes,” says Patty Lovera, assistant director of Food & Water Watch. “The economic power of the Big Four gives them a lot of political weight to push back against USDA inspectors’ efforts to enforce existing rules and to fight against any tighter safety standards being enacted.” And, she adds, “the sheer volume of beef that big-company plants crank out means that a quality control mistake at a single plant can lead to packages of contaminated beef ending up in stores and restaurants across 20 or 30 states.”

The better burger starts here

Image courtesy of Consumer ReportsCattle can have a healthier (and more humane) upbringing if they graze in pastures for most—if not all—of their lives. “The most sustainable beef-production systems don’t rely on any daily drugs, don’t confine animals, and do allow them to eat a natural diet,” Rangan says. And what’s good for cows is good for people, too. “Our findings show that more sustainable can mean safer meat.” That’s why Consumer Reports recommends that you buy sustainably raised beef whenever possible. Sustainable methods run the gamut from the very basic ‘raised without antibiotics’ to the most sustainable, which is grass-fed organic.

“We suggest that you choose what’s labeled ‘grass-fed organic beef’ whenever you can,” Rangan says. Aside from the animal welfare and environmental benefits, grass-fed cattle also need fewer antibiotics or other drugs to treat disease, and organic standards and many verified grass-fed label programs prohibit antibiotics. Sustainably raised beef does cost more, but it’s the safest—and most humane—way for Americans to enjoy our beloved burgers . . . cooked to medium, of course.

How much bacteria is in beef?

We tested 300 samples of conventional (181 samples) and more sustainably produced (119 samples) of raw ground beef purchased at supermarkets, big-box, and “natural” food stores in 26 metropolitan areas across the country. We classified beef as being more sustainably produced if it had one or more of the following characteristics: no antibiotics, organic, or grass-fed. Here are the percentages of samples in each type that contained each of the five bacteria we tested for and the samples that contained two or more types of bacteria.

Where superbugs lurk

Superbugs are bacteria that are resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics, making infections caused by them difficult if not impossible to treat. In our tests of 300 samples of raw ground beef, we found that conventional beef was twice as likely to be contaminated with superbugs than was all types of sustainably produced beef. But the biggest difference we found was between conventional and grass-fed beef. Just 6 percent of those samples contained superbugs.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.