FBI Director Wants To Change Law To Allow Easier Snooping On Smartphones

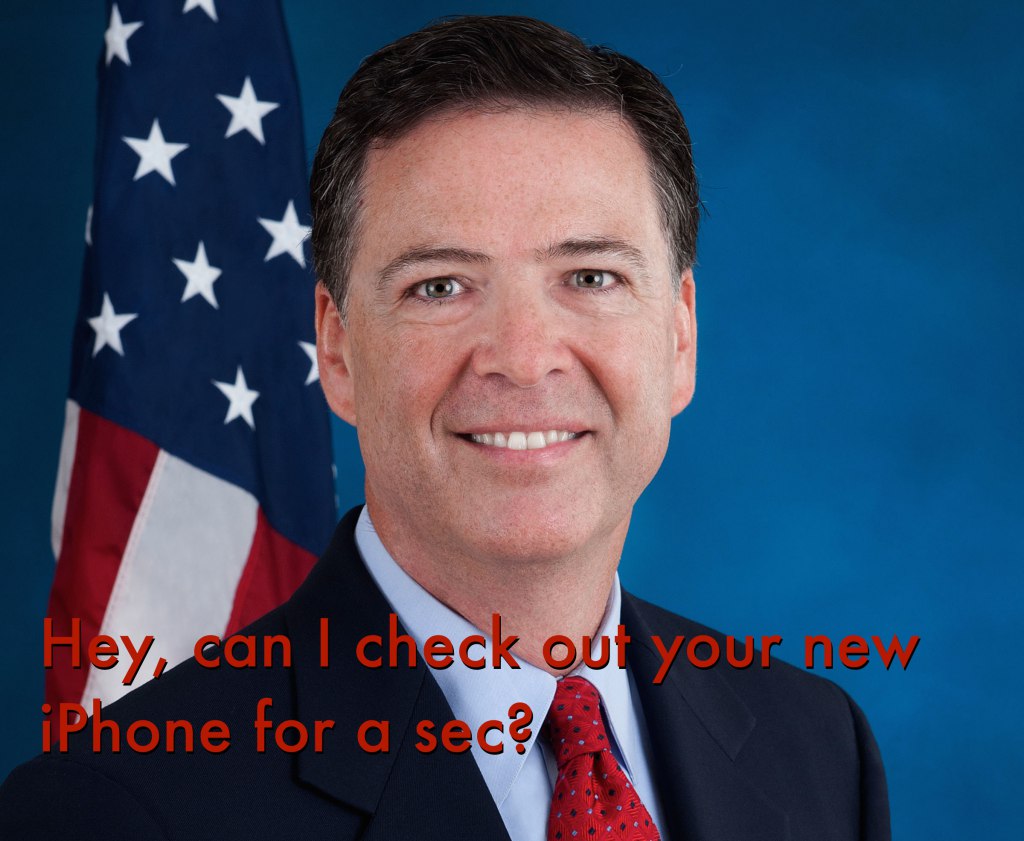

Last month, FBI Director James Comey expressed vague concerns that new privacy measures on iOS and Android smartphones might allow criminals to do bad things. Now Comey is saying it’s time to change the law to make sure that law enforcement doesn’t have to figure out your phone’s password.

Last month, FBI Director James Comey expressed vague concerns that new privacy measures on iOS and Android smartphones might allow criminals to do bad things. Now Comey is saying it’s time to change the law to make sure that law enforcement doesn’t have to figure out your phone’s password.

Thanks to the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the police have relatively easy access for warranted monitoring of telephone and Internet communication, by requiring that providers build in a way for authorities to tap into these connections.

But recent changes to Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android operating systems throw a wrench in CALEA because they give users a way to secure the data on their devices in a way that doesn’t allow either company to remotely unlock them.

So while police can get a warrant and listen to your calls, access cloud-stored data, possibly see your texts and e-mails, they would ultimately need to figure out a device’s passcode to access information that is stored only on your phone.

This worries Comey, and outgoing U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, both of whom have claimed that this additional layer of privacy protection would allow criminals to do criminal things.

Now Comey is arguing that it’s time to change CALEA to compel companies not currently covered by the law to build in a “front door” for law enforcement access.

“Thousands of companies provide some form of communication service, and most are not required by statute to provide lawful intercept capabilities to law enforcement,” the Director said on Thursday during a speech at the Brookings Institution. “What this means is that an order from a judge to monitor a suspect’s communication may amount to nothing more than a piece of paper.”

Comey directly addressed the security updates recently announced by Apple and Google, saying, “Both companies are run by good people, responding to what they perceive is a market demand. But the place they are leading us is one we shouldn’t go to without careful thought and debate as a country.”

Then, in an effort to use metaphor to bolster his point, Comey inadvertently shoots his argument in the foot.

He says that encryption is “a closet that can’t be opened. A safe that can’t be cracked.”

Exactly. Locked closets and safes have been around for centuries, but the police don’t have master keys so that they may easily gain entry just because they think something bad is hidden therein.

Similarly, people have been using encryption and passcode protection on personal and business computers for decades but it’s been up to law enforcement to try to get around that protection when performing a search.

So why should the police have any sort of special access to smartphones? Just because it is both a telecommunications device and a computer that stores information?

As we’ve repeatedly stated in recent weeks: Neither consumers nor electronics manufacturers have an obligation to make it easier for law enforcement to do their jobs. And just because you don’t want authorities looking at the photos stored on your phone doesn’t mean you have anything to hide.

“When we accept the premise that full access to everyone’s communications is required, there will be no end to access government can demand to your smart home, smart car, and so on,” cautions lawyer Albert Gidari Jr., to the Washington Post, “just because a bad guy somewhere might use such a device in furtherance of a crime.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.