9 Things You Need To Know From Frontline Investigation Of Antibiotics & Animals Image courtesy of Frontline

Last night, PBS’ Frontline aired a report on the huge amount of antibiotics that farmers pump into animal feed and the effects that this practice has on the development and spread of antibiotic-resistant superbugs that kill thousands of Americans and make millions more sick every year.

You can watch the whole show here on the Frontline website, along with oodles of supporting segments and related reports, but we’ve boiled down the most important take-aways from the show.

1. THE FDA TRIED TO CURB THIS PRACTICE 37 YEARS AGO

The first major governmental report raising concerns about the over-use of antibiotics in animal feed actually came out of the U.K. in 1969, the so-called Swann Report, which raised a warning flag about the increase in drug-resistance among animals fed antibiotics solely for growth-promotion.

“This was a milestone report,” explains Gail Hansen, D.V.M., from the Pew Charitable Trusts. “They said antibiotics shouldn’t be used to get the animals to grow faster because one of the unintended consequences was antibiotic resistance. Yes, it was an economically short-term good, but in the long term, antibiotic resistance was a real problem.”

It was still almost another decade until any U.S. regulatory body tried to do anything.

In 1977, then-new FDA Commissioner Donald Kennedy proposed restrictions on two widely used antibiotics, penicillin and tetracycline, on farm animals.

“We’re creating resistant organisms that may ultimately transfer that resistance to organisms that cause human disease,” Kennedy said at the time.

“I thought we were doing exactly the right thing,” the former Commissioner laments in the present day. “The trouble is that you don’t always find that as easy as you had hoped.”

That hope was dashed by the drug and farming lobbies, who told Congress that the FDA was behaving in a “wholly illogical” manner that the proposed rules would result in an “arbitrary and capricious, thus illegal regulation.”

In Congress, opposition to the FDA proposal was embodied by Mississippi Congressman Jamie Whitten, whose authority earned him the nickname of “Permanent Secretary of Agriculture” and for whom the USDA office building in D.C. was renamed in 1995.

“We were at the mercy of Representative Whitten,” recalls one of Kennedy’s aides from his FDA years. “[Whitten] basically made it clear that unless we got much more scientific evidence, he was going to cut the heck out of the FDA budget.”

2. RESISTANCE IS ON THE RISE, REGARDLESS OF THE SOURCE

Elizabeth duPreez, Pharm.D., an infectious disease pharmacist in Flagstaff, AZ, says her hospital has taken in an increasing numbers of people with drug-resistant urinary tract infections in recent years.

“We’re seeing a lot more patients that were… normally healthy have to be admitted because they’ve gone through multiple outpatient courses of antibiotics and haven’t improved,” she tells Frontline. “At the point that they come in, that bacteria has gone into their bloodstream, and that requires immediate hospitalization.

“You don’t have normally healthy 30-year-old woman, who’s never been in a hospital, with a resistant urinary tract infection that’s moved into her blood,” she points out. “Where did she get that organism from?”

Tom Chiller, M.D., Associate Director of the Centers for Disease Control, explains, “We see resistance pretty much everywhere and in everything we test. So there is a certain amount of resistance in cattle, in pigs, in chickens, in humans, in the retail meat that we buy in stores. Anywhere you use antibiotics you’re going to have resistance and propagate resistance.”

3. WHY IS IT SO HARD TO CONVINCE THE MEAT AND DRUG INDUSTRIES OF A RESISTANCE ISSUE?

It’s that very omnipresence of resistance that makes it difficult to show definitive evidence linking cause and effect.

“It’s very challenging to link the use of a particular antibiotic in a particular herd of animals to a particular illness,” says Chiller. “So going from point A to B to C to D to E to F — tracing that bacteria all the way to person A with resistance A; that’s very challenging to do because there are lots of steps in between.”

And without that smoking gun evidence, neither the drug nor livestock industries are going to budge on their “show us the proof” stance.

“I’m not saying the use in animal agriculture doesn’t contribute to resistance at all,” says Christine Hoang, D.V.M., Asst. Dir. American Veterinary Medical Assn. “Of course, we see resistance in veterinary medicine from the use of antibiotics. But there’s a lot of unknowns as well. We really have not shown that direct pathway from ‘You gave this animal that drug and some person somewhere down the line ate meat from that animal and they now have a resistant infection because you gave that drug way back here.’”

4. LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

After reading reports from Europe about drug-resistant MRSA infections being transferred from swine to those in the immediate environment, researchers here in the U.S. attempted to find out if that was happening stateside.

They looked at millions of medical records for hundreds of thousands of patients in a large swath of rural Pennsylvania that contains a lot of large swine-feeding operations. And according to their data, between 2001 and 2009, the number of MRSA incidents increased each year, sometimes by upwards of 34% year over year.

Additionally, when they overlaid the addresses for MRSA patients with locations for feeding operations, they believe they have detected a pattern:

The red dots represent the homes of MRSA patients in the region. The gray markers indicate the locations of large pig-feeding operations.

“There’s some nice overlap you’ll see between where the MRSA cases are and where the swine farms are,” explains Joan Casey, Ph.D., one of the researchers behind the study. “You can see that there are some folks with these infections living very close to animal feeding operations.”

She and her colleague, environmental epidemiologist Dr. Brian Schwartz, believe that a possible reason for the spread of MRSA from farms to humans is through the use of animal manure for fertilization.

“When you have antibiotics in animal feeds, the manure is loaded with undigested antibiotics,” explains Schwartz. “It’s loaded with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and it’s loaded with the genes that the bacteria can transfer back and forth to each other that allow them to become resistant.”

So if you load a crop field with this manure and there is a torrential storm, it could all run off into nearby streets and yards. On the flip side, if you have a particularly dry period, the manure-covered soil could turn dusty and become airborne.

The drug industry is still not impressed with this study.

“I think the study was very interesting and it showed some association but I think the implication is that antibiotic use somehow caused the problem, and there’s no evidence that that is the case,” says Richard Carnevale, D.V.M., VP of drug industry group the Animal Health Institute. “They didn’t test any of the manure, so they have no data on what was actually in the manure.”

Schwartz contends that they couldn’t test the manure because they need to get permission to go onto private farmland and “getting access to the farm operations has not been easy.”

“We have not made any definitive links,” says Casey, whose research found that those living close to animal farms and crop fields sprayed with manure were 38% more likely to be infected with MRSA, “but I think there’s mounting evidence that there’s a problem.”

When asked if it’s possible that farms could become the same sort of breeding ground for drug-resistant germs that hospitals have become, CDC’s Chiller replied, “It’s not only possible, it’s happening.”

5. GENETICS MAY BE THE KEY

Researcher Lance Price and his team have spent two years trying to see if there is a direct genetic link between drug-resistant e. coli bacteria found in retail poultry purchased in the Flagstaff area and local cases of drug-resistant urinary tract infections.

“We started this study because we had this hypothesis, this theory, that food could serve as a source of e. coli,” he explains.

Researchers paid particular interest to strains of e. coli that could cause infections of the bladder or kidney, or any other infection that can get into the bloodstream.

Price’s team found that 20% of tested meat had these bad strains of e. coli and that one-third of those bacteria were resistant to multiple types of antibiotics.

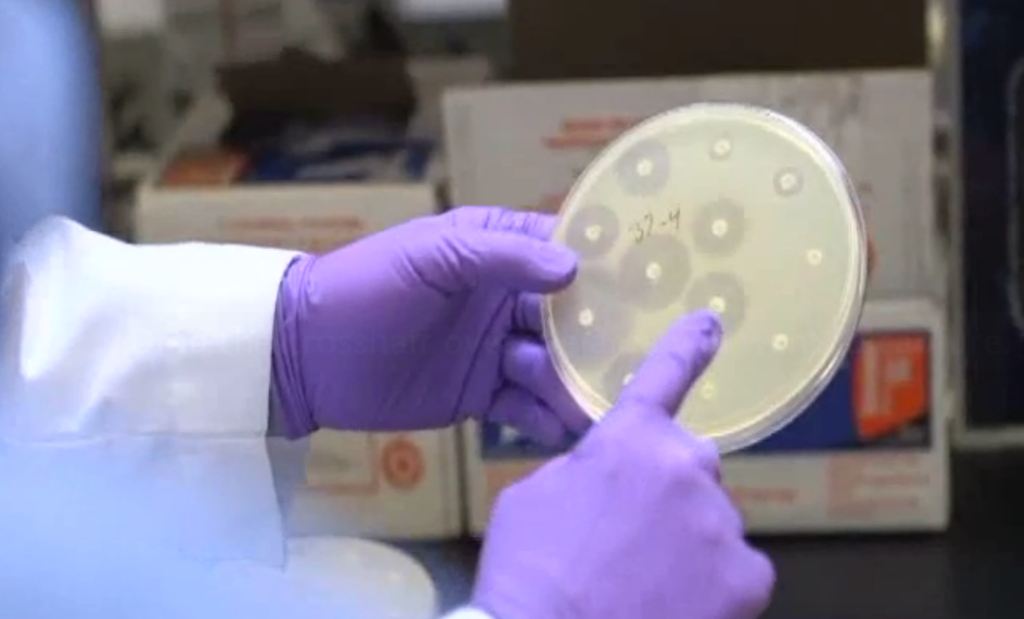

You can see by the small or nonexistent reactions around the dots on the right that the e. coli in this petri dish is resistant to those particular antibiotics.

“That’s five different antibiotics that a physician can’t use,” says Price.

His research is still ongoing and has yet to be peer-reviewed, but the early purported results are promising if accurate.

Price claims to have genetically linked more than 100 urinary tract infections back to supermarket meat products, with about 25% of them being resistant to multiple antibiotics.

“When we see such genetic relatedness as this, the alternative explanations become… impossible,” he tells Frontline.

6. WHAT’S NOT IMPORTANT TO YOU MAY ACTUALLY BE INCREDIBLY IMPORTANT TO EVERYONE

Two Texas veterinary medicine researchers noticed that drugs in the cephalosporin class were losing their effectiveness among cattle. Not only did this make it harder to treat the cows, it raised concerns because these drugs are of critical importance to human beings.

“They’re so critically important because there are certain types of infections for which they are one of only a few choices available to treat these infections,” explains H. Morgan Scott, Ph.D., of Texas A&M.

Scott gives the example of clinical salmonellosis in children and many pregnant women. Cephalosporins might be the best, or possibly only choice to treat.

He and his colleague Guy Loneragan from Texas Tech had hoped they could decrease the use of cephalosporin and increase the use of tetracyclines in cattle as these latter drugs are older and no longer as critical to human health.

“Most of the world doesn’t care about tetracycline resistance,” says Scott. “They care a lot about cephalosporin resistance.”

Problem is, ramping up the level of tetracycline use made things worse.

“We actually saw that resistance went up, which is not what we hypothesized,” says Loneragan. “Our viewpoint historically has been that, sure tetracyclines aren’t that important for human health so why worry about them in animal agriculture? But they may be more important than we think, not because of their use in human medicine, but because they can expand resistance to critically important drugs.”

7. THE DRUGGED-UP VEIL OF SECRECY

Farmers know exactly what they’re giving to their animals and why, but that’s essentially where the sharing of information stops, as there are no requirements for farmers to report how many antibiotics go into their animals’ feed, which types are being used at any given time, or why they are using the antibiotics.

The CDC’s Chiller says that his organization and others that want to track resistance have made it very clear that they want data not just on the quantities of antibiotics being purchased, but on the actual usage.

“I think we’ve been clear for years… that we would like use-data,” says Chiller. “To be able to understand resistance and where it’s coming from, it’s gonna help a lot for us to have better use data so that we understand how these antibiotics are being used and whey they’re being used.”

Unfortunately, the CDC doesn’t have the authority to compel farmers — or even politely nudge them — to share this information. That lies with the Food and Drug Administration, which has only recently shown any renewed interest in drug-resistance.

When questioned by Frontline about why the FDA isn’t demanding more detailed usage data from farmers, Commissioner Margaret Hamburg explains, “I think it’s a question of us all working together to identify what are the critical data needs.”

Frontline’s David Hoffman, who to this point in the show has maintained some level of impartiality, seems confounded by this statement.

“Don’t you know that now?” he asks Hamburg. “After 40 years, shouldn’t you have a better handle on that?”

To which the Commissioner non-responds, “You’re asking a very big question in terms of the overall picture. We are focused on certain aspects of this challenge.”

Gail Hansen of the Pew Charitable Trusts, believes that the FDA is still smarting from the beatdown it took from Congress nearly 40 years ago on this topic.

“I think FDA is taking some baby steps,” she says. “They could be much bolder.”

There have been legislative attempts to require more detailed reporting from farmers, but they have been quieted with the backing of industry lobbyists.

However, one particularly uncharismatic representative of the National Pork Producers Council denies having lobbied against these laws because they already lacked support in Congress (presumably thanks to preemptive lobbying, but that’s a drugged-up chicken/egg debate for another time).

What is very revealing is Big Pork’s explanation for why it wouldn’t want these very laws it claims it didn’t lobby against.

“People who are asking for that information are people whose motives were to restrict antibiotic use,” explains the rep.

When the industry doesn’t have a better spin than “It would result in the very thing our opponents want,” maybe there’s something to the demands for that information.

8. VOLUNTEERING ISN’T WORKING

FDA Commissioner Hamburg defended her heavily criticized decision to ask drug companies to voluntarily stop selling drugs to farmers solely for growth-promotion.

“We actually believe that by taking a voluntary approach, we are going to move towards our goal of getting these antibiotics out of use for growth-promotion in a more effective and speedier way than if we actually tried to go drug by drug to pull them from the marketplace,” she explains.

But Hoffman points out to her that the drug industry itself claims that only 12% of animal antibiotics are used solely for growth-promotion, which means that 88% of all animal antibiotics will continue to be used as before.

“The action we’re taking is one step,” says Hamburg. “We clearly need a comprehensive strategy in terms of animal health and farm practices as well… we view what we’re doing as part of a broader process.”

Researcher Price says it’s all for nought without that usage data.

“If they’re not collecting the data to verify that people are changing the way they’re using antibiotics, that the program is working, what’s the use?” he asks. “How do we evaluate the success of this program without collecting data?”

9. FOCUSING ON THE WRONG QUESTION?

While so many researchers are hunting for that piece of definitive evidence proving that resistance and drug-resistant bacteria pass from animals to humans, maybe that’s missing out on the bigger picture.

“We live in a shared environment,” says Texas Tech’s Loneragan. “Bacteria that we can find in animals, we can find in people. And bacteria that we can find in people, we can find in animals. So the route by which they move between them may not be that important, but the fact that they move between populations is important.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.