Let’s Count The Ways In Which The NY Times’ Love Letter To The Comcast Merger Is Full Of Bull

Yesterday, the NY Times’ “Common Sense” column demonstrated anything but common sense in a thinly-veiled love letter to Comcast CEO Brian Roberts, who is apparently the savior of cable TV and will somehow bestow wonderful, magically-awesome levels of customer service on Time Warner Cable… if only those big-bad regulators in D.C. would just see what is so obviously a perfect deal for consumers. If only that were true.

Let’s look at author James B. Stewart’s article and try to figure out exactly how much Kabletown Kool-Aid he’s consumed…

1. Ignoring Comcast’s Role In Current State Of Cable TV

Early in the article, Comcast-inheritor Roberts laments the current state of cable competition, in which a company’s presence is often determined by deals made with municipalities many moons ago.

“Cable is a relic of an antiquated model,” admits Roberts. “The result is we’re not in New York or Los Angeles. How great can that be?”

In a sense, he’s right. Comcast should have been in New York City and/or Los Angeles, but not as the sole provider like TWC is for many of the residents of those two cities. No, Comcast should have been able to compete with everyone else, giving consumers choice and compelling providers to compete on rates and customer service.

But Roberts can not wash his hands of the situation that he (and his company-founding father before him) played no small part in creating, and from which Comcast has benefited greatly.

Take the Philadelphia area, which has long been dominated by Comcast, but which used to have multiple regional providers serving different parts of the region. In the last two decades, Comcast has gobbled up most of those companies, creating an effective monopoly in the area thanks to all those exclusivity deals each of the acquired providers had made in the ’70s and ’80s.

Furthermore, while Philly leadership pretends it’s about prettying up the city, a recent move to regulate and remove satellite dishes from buildings all around the city has Comcast written all over it.

And don’t forget Boston, a city is so ridiculously overrun by exclusive Comcast coverage that former Mayor Thomas Menino had to petition the FCC to allow the city to regulate the company’s soaring prices.

It is the cable industry, including Comcast, that sought these sorts of deals and guarantees, and which has allowed them to continue because they allow providers to get away with charging high rates and providing minimal customer service.

Roberts even admits as much later in the Times piece, when he says the only feasible way for Comcast to be a player in NYC is for it to buy Time Warner Cable, as it would be too expensive to run its own lines.

2. No One Asked Us…

Stewart then goes on to make a completely asinine statement about those who are against the Comcast merger:

The sheer size of the deal, and the intense public interest in unfettered Internet access, have galvanized an array of opponents, from Senator Al Franken, Democrat of Minnesota, to the Consumers Union to the Writers Guild of America…I suspect few of them, if any, are Time Warner Cable customers.

Let’s just look at how utterly, absolutely stupid of an assumption that is.

First, I’m not going to speak for my colleagues at Consumers Union, but I happen to know for a fact that they — and many other employees of Consumer Reports, including myself, and several other Consumerist writers — have had, or currently have, cable and Internet service from Time Warner Cable. Consumers Union’s headquarters is located in Yonkers, NY, only a few miles north of NYC, and many of CR’s employees live in areas where TWC is the only option. A simple phone call or e-mail, and anyone at the company would have told Mr. Stewart so.

And then there’s the Writers Guild, which has a large number of members in New York City (that’s why there is a WGA East office in Manhattan, Mr. Stewart.) All those writers for Comcast’s own Saturday Night Live and Tonight Show are probably TWC customers. That’s not to mention all the people who write for the soap operas, talk shows, and the various series that film in NYC. Again, I’m sure someone at the Guild, or the use of the author’s much-touted common sense, would have sorted this one out.

I don’t know Sen. Franken’s current living situation, but I do believe he’s lived in NYC at some point in the past 25 years, since he used to broadcast his Air America radio show from Manhattan, and worked on Saturday Night Live in the early ’90s, which means he’s likely to have been a TWC customer at some point.

3. Personal Bias Is A Bad Measuring Stick

Let’s just assume that Mr. Stewart’s ill-informed attempt to discredit merger critics was based in actual fact and that none of these people concerned about a merger between the nation’s two largest cable and Internet providers have ever had to deal with TWC’s horrendous service.

What does that matter?

Did one need to be either an AT&T or T-Mobile customer to oppose that failed merger? Does he think that members of the FCC and the DOJ are going to say, “Well, I can’t be part of this decision because I’m a DirecTV gal”?

In fact, it may be best if the people making the decision have minimal experience with either provider, as their personal biases can’t get in the way. The last thing I want is some regulator deciding they will approve this merger because they once got double-billed by Time Warner Cable and somehow think this merger will stop such nonsense from happening in the future (Spoiler Alert: It won’t.)

Speaking of which…

4. The Grass Is Always Slightly Less Brown

Stewart seems to be living under the delusion that Comcast’s customer service couldn’t possibly be worse than TWC’s. He even cites J.D. Power regional ratings to back up his point, saying that TWC was the lowest-rated in almost every region for its pay TV service. And this is indeed true.

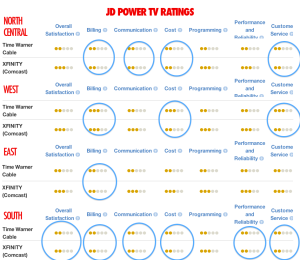

A summary of the JD Power ratings for Comcast and TWC’s pay-TV services. We’ve circled all the instances in which the two companies scored the same or in which TWC outscored Comcast. Note that neither company managed to do better than a 3 on the JD Power scale, indicating a score of “About Average.” Click chart for full-size.

What the author at the venerated newspaper omits is a link to the JD Power study, as that would show that Comcast performed just as poorly half of the time, and the instances in which Comcast outscored Time Warner Cable, it did so only marginally (a fact Stewart waits until the very end of the story to even mention before allowing Roberts to shrug it off with all the awesome super-rad tech that will help curmudgeonly Stewart finally find Mad Men on his cable listings… Kids today!). Nowhere in the seven rated categories for each of the four regions does either company score better than “About Average.”

And you’ll notice that of all the companies that rank or rate TV and Internet providers, Stewart cherry-picks one that sort of helps to make the case that Time Warner Cable is a bad company.

In fact, there are multiple sources that would have indicated the same thing, but which would have also shown that Comcast is just as bad, if not worse.

Circling back once again to our colleagues at Consumer Reports, whose recent survey of telecom providers turned up equally bad results for the two merger partners, and where Comcast received especially low marks for customer support.

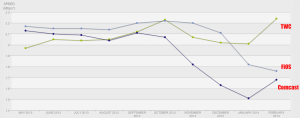

Recent data from Netflix showing how Verizon and Comcast have allowed its downstream speeds to slow to a crawl during the last half of 2013, while TWC continued to provide adequate support for the service. Click for full-size chart.

Stewart conveniently left out this information from Netflix, showing that Time Warner Cable downstream speeds have remained sufficient, and even improved, during the months that the all-great Comcast passive-aggressively throttled Netflix content by allowing it to bottleneck until the Internet’s biggest traffic consumer decided to pay the toll.

And the folks at the American Customer Satisfaction Index, whose latest ratings of pay-TV companies and ISPs showed both Comcast and Time Warner Cable bringing up the rear in the two categories. Comcast was the bottom-scraper when it came to Internet service, while it allowed TWC the honor of being the caboose on the pay-TV train.

Neither company has provided any shred of evidence that customer service, billing, or reliability will improve post-merger. There has been lip-service paid to the notion that by combining their assets, they will be better able to invest in much-needed resources.

But given the potholed track record of these two companies, why would we have any reason to believe that savings on manpower, networks, maintenance, and content will be reinvested in improving customer service when all a merger would do would be to create an even larger company with minimal competition and even fewer reasons to provide competitive rates or customer service?

5. The Myth Of Geographic Overlap

Here’s the argument you hear repeatedly from Stewart and other cheerleaders for this merger: Comcast and Time Warner Cable don’t currently overlap, so it’s not really creating a monopoly.

It’s a valid point, and one that those opposed to the merger will have to repeatedly rebut in the coming months, but it’s a deflection of the bigger issues involved here.

Because the cable industry has virtually no competition — even the large satellite companies can’t compete in providing broadband services — they can get away with things like unexplained rate increases; new fees for old products and services; using customers as hostages in blackout battles with broadcasters.

Far from giving Comcast a reason to pass savings on to customers, a nearly-doubled subscriber base could actually provide the company with an incentive to continue nickel-and-diming customers. An extra dollar a month from 30 million customers is a nice chunk of change at the end of the year. Data caps and usage-based pricing for Internet users would be a gold mine for the merged company, especially since their consumers have few-to-no alternatives for broadband service.

Stewart mocks the notion put forth by law professor and author Susan Crawford, among others, that a merged Comcast/TWC would create a “monopsony,” a company that would effectively be negotiating with vendors on behalf of an entire industry. The mega-provider would be able to demand the absolute lowest rates from networks and other providers, which Stewart sees as only resulting in good, claiming the future Comcast-zilla “has an incentive to pass at least some of those savings on to customers to increase demand for its services with lower prices.”

Again, we ask where he’s imagining this incentive coming from? If Comcast has no competition and customers can’t get their Internet and TV service elsewhere, why on Earth would the company not continue to chisel away at subscribers’ wallets?

6. Who Cares About The Broadcasters?

Continuing on with the discussion of creating a monopsony, the Comcast ad in the Times — (because that’s what it is: a huge, effectively sponsored, story that only cost Comcast a few bucks to get Stewart to Philly and show him around its shimmering USB drive on JFK Blvd.) — rightfully points out that antitrust law is intended to protect consumers, so why should anyone care about broadcasters and other content creators not getting their full due?

“It’s hard to imagine that the wildly popular ESPN or Netflix needs protection from regulators in Washington,” writes Stewart, ignoring the ripple effects and other problems associated with monopsony.

Say Comcast goes to Sony to discuss online streaming rates for its TV and movie studios’ content. The mega-company, which not only has cable customers, but also Internet users, a built-in TV audience on a major broadcast network, multiple news channels, and a slew of cable offerings, could use that leverage to guarantee it pays a lower rate than anyone else in the industry. This drives up rates for competitors, who either pass that cost on to customers or who have to be more selective about what they license for their customers’ use.

It provides a barrier for entry to start-up companies or new ventures from existing companies; makes it harder for smaller, regional providers to grow and compete; and could drive some companies — on both the content and provider side — out of business. Less choice, higher prices. That’s a consumer issue, Mr. Stewart.

Additionally, cable companies are the gatekeepers for much of the information entering Americans’ homes. With no current net neutrality rules, a cable company can literally decide what its customers can and can’t see. Even though Comcast is still obligated to oblige by the recently-gutted rules through 2018, the above-referenced Netflix standoff shows that it has the means and the leverage to get around such weak-kneed regulation.

7. Someday My Cable Prince Will Come…

Stewart makes the fallacious claim of an “array of consumer television and broadband options” available to consumers, disregarding all studies showing that very few people have access to more than one cable provider; that satellite TV customers generally need a cable company to get broadband; that Verizon has stated publicly that it has no immediate plans to build out its FiOS fiber network into new areas of the country.

He even made me laugh a bit by speculating that Google may bring its Google Fiber network to New York City at some point in the next millennium. Verizon, which has the poles and the existing landline network in place, has been trying to wire that city for years with FiOS and has barely made a dent in Manhattan and many of the more populated areas of the city.

I actually did a spit-take when Stewart tossed out the suggestion that Sprint’s pie-in-the-sky plan to provide wireless broadband service would someday be a viable non-cable option for consumers. At this point, that idea exists only in the speeches that SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son gives to make the case for his own desired merger of Sprint and T-Mobile USA. Yes, widespread broadband Internet seems like an inevitable future for data to the home, but it’s unlikely to come from any of the major wireless providers who are currently too busy enjoying their tiered data plans and their associated overage fees. And the notion that Sprint, which has not been able to keep up with its competitors in terms of speed and reliability, would be the superhero to swoop in and provide competition to New Yorkers is just ludicrous.

You simply can’t wipe away all the problems with this merger with a few glib, biased complaints about how much you currently hate Time Warner Cable. You can’t just say that the deal won’t create a monopoly because there already is one. You can’t pin your hopes for future competition on what-ifs and maybes.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.