The Future Will Not be Televised: Comcast’s Merger Plans are All About Broadband

Comcast and Time Warner Cable are cable companies: they run their wires to little boxes in our living rooms so we can watch Mad Men and Game of Thrones. But even though roughly 100 million Americans subscribe to pay TV, that’s not what the merger between the two companies is about. The future of entertainment is online, and that access is what’s really at stake in the proposed merger deal.

Comcast and Time Warner Cable are cable companies: they run their wires to little boxes in our living rooms so we can watch Mad Men and Game of Thrones. But even though roughly 100 million Americans subscribe to pay TV, that’s not what the merger between the two companies is about. The future of entertainment is online, and that access is what’s really at stake in the proposed merger deal.

Everybody watches TV… for now

Until recently, the pay-TV industry — cable, satellite, and fiber all together — only ever grew. From quarter to quarter and year to year, subscriber numbers went only and always up, even if occasionally not as quickly as cable operators might hope.

All that has changed since 2011, though. That’s the year when pay-TV subscribers peaked, at just shy of 101 million. Since then, all of the big TV operators have seen at least some quarters with losses rather than gains, and in two years the industry overall has shed a few million subscribers. As more and more young adults raised on a media diet of YouTube and Netflix grow up and move out, a decent percentage of them are forecast not to bother ever buying cable subscriptions.

Researchers predict that by 2017, just a few years from now, subscriptions will have dropped by 5% or more, to below 95 million. And while 95 million is still an awful lot of viewers, the long-term trends do not look good for TV-only companies.

More than TV

But of course, Comcast and Time Warner Cable are not TV-only companies; they’re some of the biggest internet service providers in the country. According to their 2013 annual reports, at the end of last year Comcast had about 20.6 million broadband subscribers and Time Warner Cable another 11 million. And those numbers keep going up. The combined company would control between 30 and 35% of the American broadband market.

And as for that American broadband market: in the most general terms, high-speed internet access in the United States stinks. We pay more and get less than our peers in the vast majority of developed countries.

How much more and how much less? A 2013 study compared the available download speeds and monthly access costs in cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. to similar packages in Hong Kong, Paris, Toronto, and a couple dozen other cities. The results are ugly.

In Seoul — not a low-cost-of-living city — triple-play (voice, internet, and TV) packages cost between $14 and $22 USD monthly. In Zurich, also not cheap, it’s between $30 and $35. US packages came in very far down the list, between $60 and $150 monthly for slower packages that often include data caps.

There is one glaring exception in American broadband, though, and that’s in cities that have fiber competition, either their own municipal network or a public-private partnership like Google Fiber. The study looked at Chattanooga, TN; Bristol, VA; Lafayette, LA; Kansas City, MO; and Kansas City, KS and found — surprise! — that compared to other US cities in the study, all four of those areas offered higher speeds at lower prices.

But the road to municipal broadband, and the competition that comes from it, is rocky at best. The cable lobby, of which Comcast is of course a prominent member, works hard to discourage states from going that route. The 30 million internet customers a post-merger Comcast would have wouldn’t have any more choice for home broadband than they already have right now.

To be fair, since TWC and Comcast operate in different markets, consumers also wouldn’t have less competition post-merger. American consumers would face a landscape a lot like the current one when it comes to home broadband. Comcast, due to size and scale, would gain even more influence over its competitors than it does now when it comes to negotiations over internet services, but nothing about the companies running wires through houses would change much in the immediate term.

The future in the air?

There is one way consumers may be yet begin to see true network competition, though: in ditching those wires altogether. The growth of mobile, wireless data connectivity has been explosive over recent years. And if Comcast ticks off enough customers through its dominance of terrestrial broadband, subscribers in the not-too-distant future may come to feel that abandoning their home network altogether is a viable option.

Recent research from Pew highlights just how quickly mobile use is already catching on. 91% of Americans now have cell phones of some kind, while 55% have smartphones and 42% have tablets.

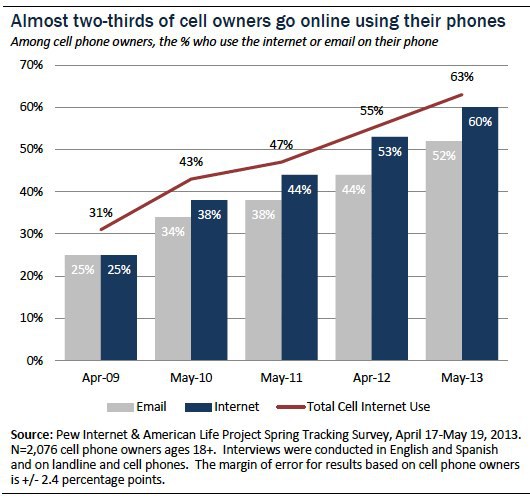

Those Americans who are getting used to having the whole of the digital world in their pockets increasingly see no reason to put down their gadgets at home. Pew finds that do 63% — a clear majority — of cell phone owners use their phones to go online. That’s a number that’s roughly doubled over the last five years.

Pew Research Internet Project, Cell Internet Use Study of 2013

Not only does 57% of the entire country (as Pew explains the math) use their phones for internet access, but a significant portion now use only their phones. Over a third–34 percent–of users who own internet-capable phones “go online mostly using their phones,” Pew says, rather than “using some other device such as a desktop or laptop computer.” For young adults, those aged 18-29, that jumps up to around 50%.

Those same young adults who prefer their iPhones and Androids to a laptop are the “cord-nevers,” who haven’t subscribed to cable for TV and aren’t likely to start anytime soon. The faster and cheaper their wireless data plans get, the less reason they have to call Comcast for any reason at all.

A shift to wireless connections would do no good for Comcast or Time Warner Cable, who once upon a time held significant chunks of the wireless spectrum but sold them off to Verizon in 2012. Verizon, meanwhile, has basically stopped expanding FiOS availability — yet another blow to competition in markets dominated by a single cable company — but has maintained dominance as a wireless carrier.

If the merger goes through, Comcast will find itself with the financial burden of upgrading TWC’s older, slower, less reliable tech in major markets like New York, while mobile carriers sit pretty on piles of broadband spectrum. It’s true that right now, consumers probably have a 20GB mobile data cap and a 300GB wired broadband cap for a very similar monthly bill, so going all wireless, all the time still isn’t practical for many subscribers. It remains to be seen when and how we could see that change.

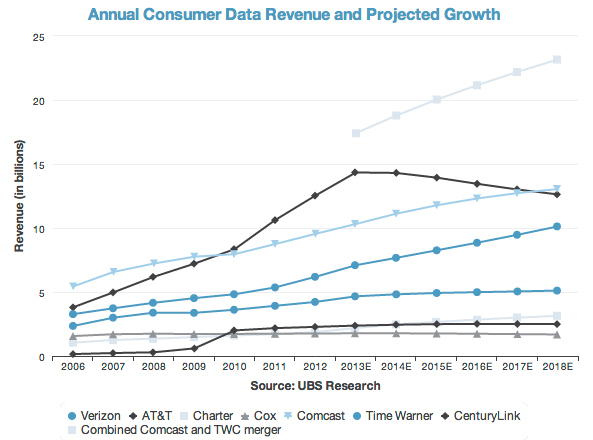

Until then, business is all about the bottom line and the bottom line is broadband. GigaOm crunched the numbers when Comcast and TWC made their announcement, and the profit margins in data service are huge. Consumers need internet access, and companies are happy to charge for it.

Graph showing projected data-service revenues for a post-merger Comcast, via GigaOm

Wired broadband service is still the fastest and most reliable way to access the internet — the “most important pipe coming into people’s homes (after power and water),” as GigaOm put it. Comcast’s stake and investment in the backbone of broadband keep growing. The more power one single cable company has to set rates, build pricing structures, and negotiate up and down the pipeline, the harder it gets for newer or smaller companies to provide alternatives.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.