Google Mocks Opacity Of National Security Requests While Feds Try To Hide Court Action From Public Image courtesy of In a transparency report from last year, Google thumbed its nose at the federal laws that limit what can be said about national security requests.

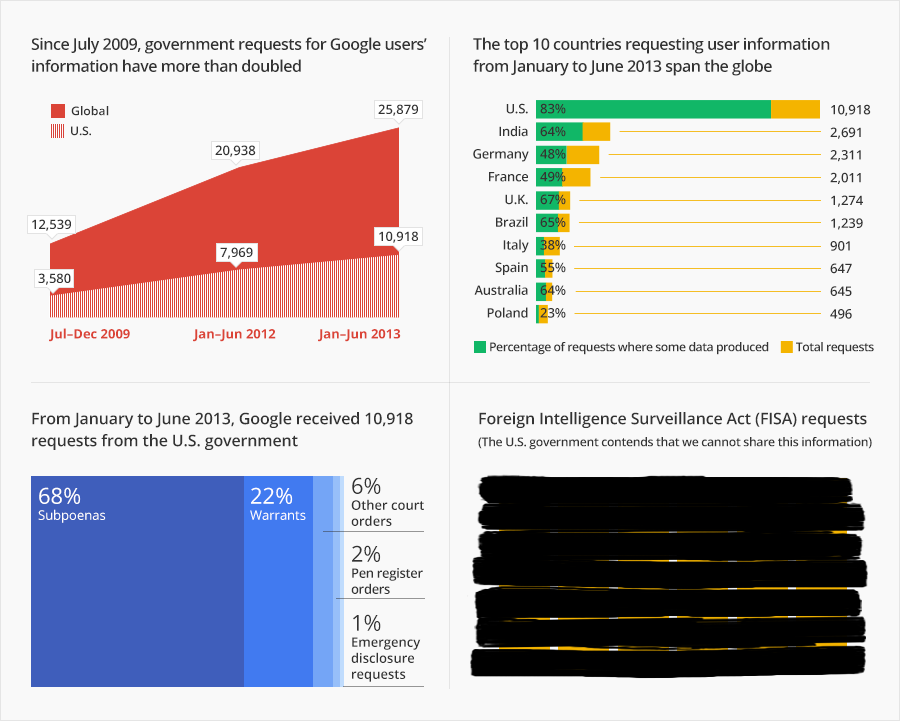

As you can see from the above graphic (courtesy of the official Google blog), in just the first six months of 2013, U.S. government filed nearly 11,000 requests for user information from Google, more than four times that of the country with the second-most requests, India.

The graph at the top left also shows the dramatic increase in the total number of government requests between July 2009 and June 2013. Globally, the total more than doubled, from 12,539 to 25,879. The increase was even sharper in the U.S., where the requests tripled from 3,580 to 10,918 over that four-year period.

But the most intriguing chart in the graph is the one you can’t see — requests made under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Google, like everyone else, is forbidden from publicly breaking out these requests from other federal law enforcement requests. Thus, the public has no idea whether or not FISA queries make up a substantial portion of that 10,918 total.

Writes Google:

“We believe it’s your right to know what kinds of requests and how many each government is making of us and other companies. However, the U.S. Department of Justice contends that U.S. law does not allow us to share information about some national security requests that we might receive. Specifically, the U.S. government argues that we cannot share information about the requests we receive (if any) under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. But you deserve to know.”

To that end, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Yahoo, and LinkedIn recently asked the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court for the ability to provide more specific information to the public about the quantity of these requests.

In a filing from September [PDF], Google told the court that it had contacted the DOJ and FBI on June 11, 2013, asking for permission “to publish certain aggregate numbers about its receipt of national security requests… The [DOJ] and FBI have not classified that information. Nonetheless, the [DOJ] and FBI maintain their position that publication of such aggregate numbers is unlawful.”

Ars Technica reports that the government has responded to this request by asking the FISC for permission to argue its side of the issue ex parte, in camera, meaning that the feds would be speaking only to the judge and that this would all take place in chambers, without the presence of Google and other involved parties.

And so Google fired back on Tuesday, filing a response [PDF] to the government’s ex parte motion, which reads, in part:

Allowing the government to file an ex parte brief in this case will cripple the providers’ ability to reply to the government’s arguments and is likely to result in a disposition of the providers’ First Amendment claims based on information that the providers will never see. The providers do not dispute that in some cases it may be appropriate for this Court to consider ex parte filings. In this case, however, such a course is neither justified nor constitutional. The providers already know the core information that the government seeks to protect in this litigation — the number of FISC orders or [FISA Amendments Act] directives to which they have been subject, if any. At issue here is only the secondary question whether the providers may be told the reasons why the government seeks to keep that information a secret. The government has not argued that sharing those reasons with the providers or their counsel would endanger national security.

We couldn’t agree more with Google’s point on this topic. It’s one thing for the government to argue that these statistics need to be kept secret. It’s another for the government to claim that it can’t reveal its rationale for why this data should be kept from the public.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.