This week, the social media world has been alight with warning about a “genealogy” site that makes just about anyone’s information — addresses (current and former), age, family members, possible associates — available for free to any user. While this has caused a minor uproar, with concerned folks telling each other how to opt out of having their data shared by this site, this sort of data-aggregating service isn’t exactly anything new — and while what this site is doing might seem remarkably creepy, it is, in fact, completely legal.

The Latest Thing

The furor this week started when Twitter user and writer Anna Brittain sent out a lengthy thread of tweets imploring everyone to immediately go to the site FamilyTreeNow.com, search for their name, view the data, and then opt-out.

The site is, indeed, unsettling. Using only a first name, last name, and state, millions of users — including most of team Consumerist — have been able to look themselves up and find a significant volume of data available on demand and available to anyone.

The site claims to have access to “billions of historical records, including census (1790-1940) records, birth records, death records, marriage & divorce records, living people records, and military records.” That’s pretty par for the course for any genealogy site, with one glaring exception: the “living people” records.

Users have expressed shock and dismay at finding incredible volumes of their personal data available for the asking on FamilyTreeNow.

For many folks, the list of possible known relatives and associates is indeed filled entirely with family members and former roommates. Various users report finding all of their full addresses going back to childhood, their siblings’ addresses, and information for their ex-spouses and former partners.

Others found that the accuracy of the records is… mixed. Users with common names, for example, may find their data chaotically intertwined with other, similarly-named folks of about the same age. Yours truly, for example, has never had family in Alabama — but some deep-south connections were suggested, by virtue of sharing names, birth months, and birth years. Whether your records are eerily accurate or bizarrely wrong appears to be hit-and-miss across users.

Opting Out

Here’s the good part: opting out appears to work… at least, more or less.

If you, too, want your “living people” data to be made unavailable from the FamilyTreeNow database, you can visit their privacy policy and then follow the directions on the opt-out page to make your data disappear.

The site may occasionally be slammed with traffic; since Jan. 10, Brittain’s tweets have since traveled far and wide, leaping off the service and making the rounds on Facebook and Tumblr as well. Every time a warning about the site hits a new node of high popularity, it ends up getting a lot of opt-out requests at once. Just wait a few minutes, refresh, and try again.

The site requests up to 48 hours to scrub living-person records from the site after an opt-out has been requested. The first big warning worked its way around the world during the day on Jan. 10; two days later, on Jan. 12, users who had opted out confirmed that they no longer see their records when they search the site. Those users likewise no longer see themselves listed as possible family members or known associates of family who do still have profiles on the site.

There are, however, some catches. One user was completely scrubbed from the site 24 hours after requesting an opt-out; another day later, their full name was again showing up in a search but clicking it leads to an error saying, “The resource you are looking for has been removed, had its name changed, or is temporarily unavailable.”

Another user reports opting several members of a single family out of appearing on the site — but says that two days after, while search results for a pair of brothers no longer yield their names, searching for their third brother brings up a list of suspected family members that includes full, clickable profile information for both of the unsearchable brothers who have been opted out.

Adding to the chaos? Some people have multiple profiles on the site, pulled together from disparate sources of information that can’t seem to peg for sure whether or not two “John A Does” with the same birthdate and address are the same person or not. If you want to opt yourself out, you’ll need to make sure you catch every profile associated with you.

More often than not, opting out appears to work successfully. But speaking with several different users who have opted out of having their data appear on the site does not reveal a clear pattern to where errors might occur, so if you want to opt out you’ll have to keep following up every 24 hours or so for a few days to make sure your own information is hidden.

Why This Site Is Different

Information about you has been available on the internet for decades. The Crash Override Network — dedicated to helping prevent internet-generated abuse, and helping its victims mitigate the effects — has links to several sites and lists that aggregate public records info that users afraid of having it intentionally leaked (or who simply value their privacy) can opt out of.

Generally speaking, sites that exist to help users compile family trees work to protect the privacy of persons who are still living. FamilyTreeNow has no such protection built in. Instead, it touts its access to your data as a selling point.

“Our living people records are some of our most in-depth,” FamilyTreeNow promises on its search page. “They have been compiled from hundreds of sources going back over 40 years. They include current and past addresses, possible aliases, all known relatives, and phone numbers. There is no other database like this on any other genealogy sites. If you need to find someone that’s currently alive or recently deceased, they will be in this database. It contains over 1.6 billion records.”

Compare that to what is arguably the best-known genealogy site, Ancestry.com, which includes language in its privacy statement that users might post information about living individuals, but are supposed to do so only with consent.

Ancestry.com also notes that some of the records included in its databases “may contain personal information that relates to living individuals, which may include you or your family members, usually from public record sources.”

“In an era of ‘democratized’ data, it is easier and cheaper than than ever to aggregate information from the public domain.”

But Ancestry is at least aware there’s an issue with that: “Ancestry and its affiliates and agents take reasonable steps to assure that the documents do not include sensitive, personal information about living individuals,” it continues.

The company also promises transparency, choice, and good data stewardship — “managing your data in a principled fashion that follows clearly stated policies and applicable laws” — all over. Those laws and policies may not mean much (more about that in a moment), but Ancestry at least does make a token effort.

Another place where FamilyTreeNow stands out? Its stated commitment to remaining 100% free to use. Most similar sites start charging for access to anything other than the most basic data, or after a certain number of searches.

“Other ‘get public records’ sites at least charged something before they gave out the info,” one concerned user told Consumerist. “That is some sort of gatekeeping.”

And it’s true: a fee is minimal gatekeeping, though that won’t block a determined stalker or harasser. It does, at least, make your information slightly less low-hanging fruit for targeting by the general public. Charging a fee to sign up for a site will deter many idle minds from bothering, because a hurdle is a hurdle.

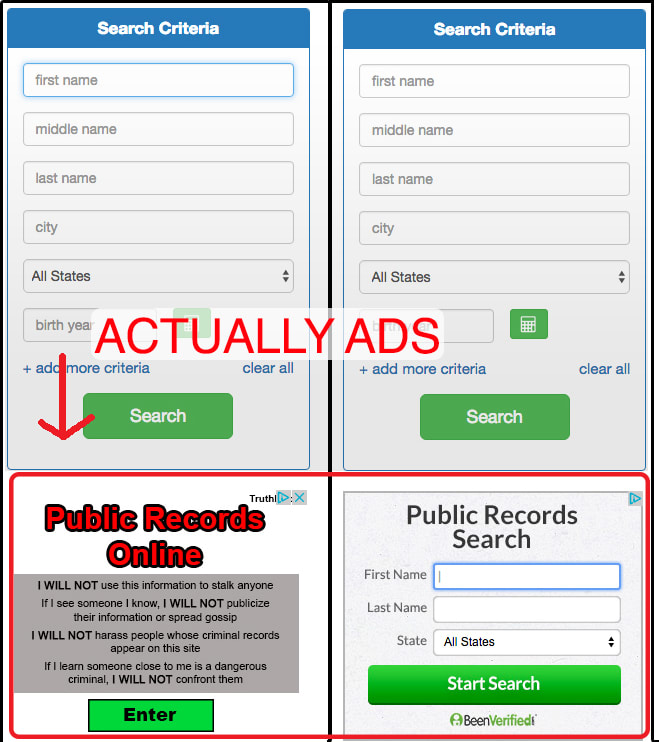

Worse: To maintain its free-to-use status, FamilyTreeNow is plastered in ads — and many of them are both misleading and misleadingly placed. For example, on the people results page, there’s an ad box immediately under the actual “edit search” box, placed in such a way that many users could easily mis-click and find themselves giving their names to less-than-aboveboard sites:

Those ads lead to a whole web of data brokerage sites, some of which are more legitimate than others — but all of which, even the non-scam ones, are out to make a buck off you.

But FamilyTreeNow has quietly been giving away your data for free for years. A commenter to the company’s largely-quiet Facebook page posted in October 2014 — well over two years ago — that she was dismayed to find “the information of living people, names, addresses, etc” available and would not be using the site because of it.

And in so doing, they are not violating a single law.

What “Personal” Means

In the days since her multi-part tweet toured the world, Brittain has written a blog post about it reminding users that this is only one very tiny slice of an overall whole.

Brittain wisely observes the catch-22 about opting out in her blog post: “The frustrating thing about these kinds of sites are two-fold,” she writes. “One, new ones pop up all the time as people become aware of the old ones and opt out. Two, your information can apparently reappear places like Spokeo after a certain period of time.”

Lee Tien, senior staff attorney at the privacy-minded Electronic Frontier Foundation tells Consumerist that FamilyTreeNow hadn’t been on anyone’s radar at the EFF until reporters started to ask about it this week, but he wasn’t surprised to hear about it.

Data aggregators, while not usually free, “are very common,” Tien confirmed.

And it’s inevitable because public records are, well, public, Tien continued. All that public records data is, every day, easily and readily available to police, governments, marketers, and even journalists. Millions of employees at thousands of public and private entities can, usually through paid means, quickly assemble profiles and dossiers about basically anyone.

To point the blame at FamilyTreeNow is effectively a case of blaming the messenger, Tien tells Consumerist, adding that users are largely “all deluded” into thinking that this data isn’t readily available.

Every single state has its own public records laws, and more exist at the federal, county, and city levels. By law, some information — including information about births, deaths, marriages, divorces, property ownership, voting history, and more — will basically always be available for the asking.

By merely existing in this world, you are going to continue to generate records. Your life, legally lived, is traceable. Your information is known and recorded, and what can be put in a database can be accessed. Until or unless the law changes in a significant way, nothing is going to alter that.

And on top of that, Tien added, is “all of the information that people volunteer.” Connections you put into a site like Facebook are purchasable and traceable — “it’s there, and it’s sensitive,” he added.

Most folks, at least, don’t have too much to worry about, Tien continued. He conceded that, “one of the threat models is the stalker, [or another] non-authority person with evil intentions.”

Those evil intentions can be part of group harassment, such as the hate mobs that coalesce around women, people of color, and LGB or transgender writers and activists in many public fields. For many public-facing workers with a Twitter presence, the discovery of easily-queried address and network information like this leads to an instant panic moment.

Even for those who are not concerned about roving digital hate mobs, the data can be a problem. One user, in a Facebook comment, initially said she didn’t see the harm in FamilyTreeNow listing off all her past known addresses, until others pointed out that these are exactly the kinds of questions credit reporting agencies use to suss out if you are actually the person you claim to be. Having data like that readily accessible in the public sphere increases the risk of successful identity theft for, well, basically everyone.

Tien is right that FamilyTreeNow is just the messenger — and as far as he or we could tell, it’s not in violation of existing law.

Rules governing your personally identifiable information — PII — are widely varied, depending not only on what the data is but also who holds it and through what means they gathered it. Information that may seem sensitive to you, like your year of birth, address, or phone number, is largely not considered proprietary or sensitive under most existing laws, and is basically fair game across the board — including for data aggregators like FamilyTreeNow to use.

“We are in a world where privacy can no longer be considered binary.”

There also is no overarching federal law governing privacy policies. FamilyTreeNow can state basically whatever it wants in its, with one important caveat: anything it states, it must hold to.

Although there are some errors, for the most part users who want to opt out report that doing so under the terms provided by the FamilyTreeNow privacy policy has proven largely effective — so it appears, from a first, casual look, as though the site is abiding by its stated terms.

If you’re terrified, though, you’re not alone.

“Consumers typically understand that public records exist about them, but they are usually unaware of the scale of that data and the ease with which it can be accessed,” Stacey Gray, policy counsel at the Future of Privacy Forum, told Consumerist.

“In an era of ‘democratized’ data,” Gray continued, “it is easier and cheaper than than ever to aggregate information from the public domain.”

That information is not protected under the law, Gray told us, because it’s the same data anyone could always get by haunting a county courthouse or vital records bureau and asking for documents. Today, though, basically anyone can access it online for free — no matter what their intent or how they plan to use it.

“There’s no doubt that this will upset many people,” Gray continued. But FamilyTreeNow, is really only shining a light “on something that was always possible, but has never been so easy.”

Perhaps the key takeaway, she concluded, is as a warning to the businesses that aggregate and sell data: “Companies should understand that we are in a world where privacy can no longer be considered binary, and respect for other values, such as ethics and fairness, will be equally critical for the industry to succeed.”

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared on Consumerist.