Your New Stormtrooper Snuggie Comes With A Surprise: It Strips You Of Your Right To File A Lawsuit

Until the other day, Consumerist reader Jeff had completely forgotten about that cute Stormtrooper Snuggie someone gave him for Christmas. When he finally opened the box, there was the Star Wars-themed sleeved blanket, and a slip of paper giving him the bad news: He had, without doing a thing, given up his right to sue the Snuggie’s manufacturer.

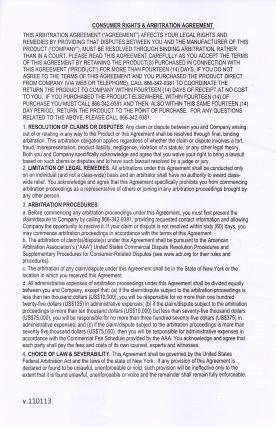

The document was titled “Consumer Rights & Arbitration Agreement,” even though Jeff hadn’t actually agreed to do anything, other than open a box.

Just like the forced arbitration agreements increasingly used by a growing list of companies, the Snuggie “agreement” states that all disputes between the the customer and the manufacturer — who isn’t even named on the incredibly generic document — “must be resolved through binding arbitration, rather than in a court.”

Additionally, like those other agreements, the Snuggie clause bars you from joining together in a class action with other Snuggie owners, even if that class action is brought through arbitration.

What makes the Snuggie arbitration agreement unlike many of the previous ones we’ve looked at is the fact that the customer does nothing to actually agree with the terms of the document.

When you sign up for services — like cellphones, cable, landline phones — you have to at least pretend that you’ve read and understand the contract. Similarly, when you make a purchase online, you’ve got to check that annoying “I understand and agree” (or whatever it says) check box, indicating that you have agreed to be bound by the terms and conditions of that seller.

New Snuggie owner Jeff didn’t even buy the stupid blanket. He just opened the box.

New Snuggie owner Jeff didn’t even buy the stupid blanket. He just opened the box.

He notes that there is an opt-out window, but unlike most companies that offer this short-term opportunity to say “no” to the deal, Snuggie owners only have 14 days.

Beyond that, it’s not really an opt-out. It’s simply an option of returning the product.

We tried calling the phone number listed in the document, and it’s just a generic answering service for what appears to be a wide range of products. Curiously, it’s also the same number you’re supposed to call when you want to resolve a dispute.

The general counsel for Allstar Products Group, the company behind the Snuggie, answered a few questions for us via email about the company’s reasons for, and use of, this arbitration clause.

“Consistent with the widely-accepted use of arbitration agreements more broadly, we introduced arbitration clauses to ensure parties in any dispute have a faster and less expensive resolution,” writes Allstar.

The company also contends that forcing arbitration helps to curb frivolous lawsuits from folks “seeking to extract settlements from companies who do not want to incur legal costs,” and that the company is passing along its lower legal costs to customers.

That said, Allstar tells Consumerist that the company has not yet used one of these agreements to compel a lawsuit out of the courtroom and into arbitration.

Is This Enforceable?

How can a company hold you to an agreement if you don’t do anything to agree? That’s a good question, says Rachel Clattenburg, an attorney with Public Citizen, who says it all depends on how much notice the purchaser has about the existence of that clause.

“An agreement is only enforceable if the purchaser had reasonable notice of the terms,” she explains. “This means that the purchaser either had actual notice (saw the piece of paper with the terms, for example) or constructive notice, meaning that the arbitration provision was displayed in such a way that a reasonable person would have noticed it.”

In other words, the manufacturer would either need to include the agreement — or something clearly indicating that such an agreement exists — on a product’s packaging, or give the buyer a fair opportunity to review and reject the terms found inside the box.

“For example, if a purchaser opened the box and the Snuggie was wrapped in plastic that was sealed with a sticker setting forth the arbitration provision, such that the purchaser had to see the sticker before opening the Snuggie, and allowing the purchaser to opt out or return the item if the purchaser didn’t want to be bound, that term would most likely be enforceable,” says Clattenburg.

Allstar maintains that its in-box notice for the Snuggie suffices as a clear notice of the arbitration agreement” and, as proof, points to the fact that Jeff saw the document alongside his new Stormtrooper Snuggie.

A Tale Of Two Samsungs

While the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld the use of forced arbitration clauses — even in situations where mounting a case is so expensive that a class action would be the only financially feasible way hold a company accountable — it has yet to settle the issue of exactly how much notice of an agreement the consumer must receive before making a purchase.

There are, however, several federal court cases that have dealt with this issue — and reached varying conclusions.

For example, in Han v. Samsung, several Galaxy S4 owners tried to sue the electronics giant, alleging that Samsung misled consumers about the actual storage space available on these phones. The plaintiff customers had each purchased their S4 at a retail store, and did not see the arbitration clause — included in a booklet, “Product & Warranty Information,” found inside the box — until after opening the package.

However, the District Court judge in that case concluded [PDF] that there was significant notice given inside of the package. The booklets — both the Samsung one and the ones provided by the various wireless service providers — containing these clauses instructed the users to “read this manual before” operating the device. Additionally, to get to the battery and and other necessary hardware in the package, the users would have first had to pick up these booklets.

Additionally, these Samsung devices included a 30-day opt-out window, which the court deemed was adequate time to read these manuals, and exercise their ability to say “no thanks” to the arbitration requirement. (Unlike the Snuggie opt-out, the Samsung clause does not require the user to return the phone.)

Yet, in another case involving Samsung, a different District Court judge reached a very different conclusion [PDF]. Norcia v. Samsung also involves a complaint about a Galaxy phone, the S4. Several owners of this device alleged that Samsung misled consumers about the phone’s speed, performance, and memory capacity.

Mr. Norcia said he didn’t know about the arbitration clause because he was never even shown the relevant information. He claims he only spent a few minutes in a Verizon store, where an employee unpacked his new S4, helped him transfer information and files from his old phone to the new one, and then sent him on his merry way with just the phone, headphones, and charger.

The court concluded that since Mr. Norcia declined to take the box with him when it was offered by the Verizon employee, he has to be treated as if he did indeed take the box. However, that ultimately didn’t matter, as the court also ruled that Samsung’s warranty booklet was not sufficient notice that he was agreeing to an arbitration clause. As such, the judge held that Norcia did not agree to the arbitration terms.

Samsung has since appealed that ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which heard oral arguments from both sides last October (see video below). At the core of Samsung’s appeal is the idea that warranty agreements are binding, even though there is no notice on the outside of packaging about them.

The Ninth Circuit should rule on this case in early 2017.

The Slippery Slope

There are two concerns with the Snuggie arbitration agreement. First is the typical forced-arbitration problem of stripping consumers’ of their Constitutional right to a day in court. Imagine a product contains a chemical that makes large numbers of people ill. Those people should be able to not only sue in a court of law, but because they are all making the same claims against the same company, they should be able to join their complaints together into a single class action. Instead, under an arbitration clause, each affected customer would need to go into arbitration on their own.

The second concern involves the potential for this to set a precedent that could lead to other retail products springing the arbitration surprise on consumers. If you can enforce a contract by simply including it inside a box, what’s to stop companies from putting anything on that contract and trying to force you into arbitration if you dispute it?

Clattenburg gives the theoretical example of a box of cereal containing a slip of paper that includes some completely outlandish declaration like, “You agree to pay $50 to Company X. If you don’t opt-out within two weeks, you owe Company X $50.”

“That would be ridiculous,” admits Clattenburg. “But it’s no different than including an arbitration provision in a consumer product with no reasonable notice of that provision’s existence.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.