Can Maker Of Web-Snooping Software Be Held Liable For Jealous Husband’s Wiretapping? Image courtesy of Jeremy Brooks

When you find out that someone is using computer software to listen in on your emails and instant messages, your first instinct — after wanting to swat them with a wet newspaper — may be to sue the snooper for illegal wiretapping, but should the company that made that software also be held accountable?

That’s the question at the center of an ongoing legal battle between a Florida man and the maker of software that allowed a jealous husband to allegedly violate federal wiretapping laws.

This story goes back to 2009, when a man named Javier became acquainted with a married Ohio woman named Catherine through an AOL chatroom on metaphysics. The two never met in person but soon began communicating on a frequent basis.

Catherine’s husband Joseph suspected his wife was chatting with other men online, and installed a program called WebWatcher, made by Awareness Technologies.

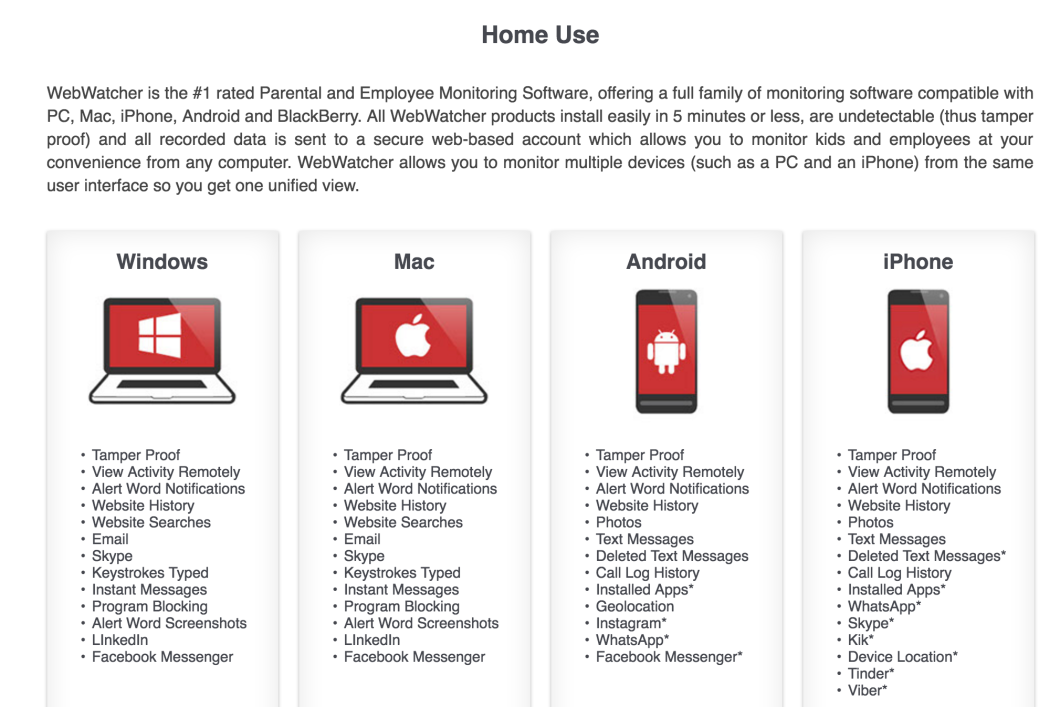

Among the features currently marketed on the company’s website, the software stealthily tracks web-browsing and search histories, emails, Skype messages, instant messages, and even records the users’ keystrokes as they type.

This information is also apparently all available for viewing remotely, which means that data is stored on a server apart from the computer or device being monitored.

In 2010, Joseph allegedly used information gleaned from these intercepted emails and other communications as leverage in his divorce from Catherine. Around that same time, Javier learned that his messages with Catherine had been recorded via WebWatcher. He subsequently filed suit against both Joseph and Awareness, alleging that the company violated federal wiretap laws restricting the interception of communications and the manufacture of devices intended for wiretapping.

Awareness asked the court to be removed from the lawsuit, contending that WebWatcher does not “intercept” communications as defined in the federal Wiretap Act, and that the company itself does not engage in any actions that would violate that law.

A federal magistrate judge concluded that while the WebWatcher tech does indeed appear to meet the Wiretap Act standard for intercepting communications, the company itself didn’t do the intercepting as it was Joseph’s use of the software that may have crossed the legal line. Likewise, the magistrate judge said Awareness could not be held liable just for manufacturing a product could be used for illegal purposes. Thus, all claims against the software company were dismissed in June 2014.

Javier appealed, arguing that the magistrate judge erred, and that he had indeed adequately pleaded all claims against Awareness. This week, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with him, reversing the lower court’s dismissal of the claims against the software company.

The Wiretap Act prohibits warrantless interception of “any wire, oral, or electronic communication.” Awareness argued that “interception” only occurs when a communication is in transit, not “after it reaches the destination where it is placed in electronic storage.” Because Joseph couldn’t use WebWatcher to spy on his wife’s emails and instant messages as they were sent, Awareness contended that the software does not violate the law.

However, the appeals panel found [PDF] that Javier should be allowed to argue that WebWatcher’s instantaneous transmission of the data to its servers indicates these messages were collected “in flight” as opposed to just being stored locally on the monitored computer.

Javier also pointed to WebWatcher marketing materials which tout “near real-time” access to the monitored information “even while the person is still using the computer.”

“This near real-time monitoring is significant,” explains the appeals panel. “If a WebWatcher user can in fact review another person’s communications in near real time, then WebWatcher must be acquiring the communications and transferring them to Awareness’s servers as soon as the communications are sent.”

The court also takes note of the marketing claim that even if a document is never even saved, “WebWatcher still records it,” which only appear to bolster Javier’s allegation of illegal wiretapping, according to the panel.

The ruling calls out the lower court for failing to recognize WebWatcher’s role in the alleged wiretapping, which “occurs at the point where WebWatcher — without any active input from the user — captures the communication and reroutes it to Awareness’s own servers… Awareness itself — not simply the WebWatcher user — ‘acquires’ the communications by rerouting them to servers that it owns and controls.”

Thus, by actively taking part in the collection of the information — as opposed to simply selling a product with which it has no further involvement — the court says it’s plausible that Awareness could be liable.

Regarding the other Wiretap Act claim, federal law prohibits the manufacture or possession of any device “knowing or having reason to know that the design of such device renders it primarily useful for the purpose of” wiretapping.

The question here isn’t really whether or not Javier could make a plausible claim that WebWatcher violates this law, but whether or not he can actually file a civil lawsuit over that alleged violation.

The Wiretap Act only explicitly allows for fines or imprisonment for violations of this particular part of the law.

The Act does allow alleged victims of wiretapping to file civil claims against those accused of engaging in the illegal interceptions, so the appeals panel had to decide whether that engagement extends to the maker of intercepting devices.

Awareness argued that the civil liability only applies to those initiating the interception, and that the law provides no way to bring a private cause of action against a manufacturer.

The Sixth Circuit appeals panel notes that other federal courts have come to varying conclusions on this issue, and concluded that courts that have adopted a narrow interpretation of the Act “have the better end of this debate,” meaning there is a higher bar for bringing a civil wiretapping claim for manufacturing or possessing a wiretapping device.

At the same time, the court said that following this narrow interpretation does not ultimately benefit Awareness.

“The present case… involves much more than simple possession,” explains the ruling. “Instead… Awareness allegedly manufactured, marketed, and sold WebWatcher with knowledge that it would be primarily used to illegally intercept electronic communications. It then remained actively involved in the operation of WebWatcher by maintaining the servers on which the intercepted communications were later stored for WebWatcher’s users.”

Thus, found the Sixth Circuit, Javier should be allowed to argue his claim that Awareness took an active role in causing the Wiretap Act violation.

Even though Awareness didn’t initiate the alleged interception of these communications, explains the court, “it is alleged to have actively manufactured, marketed, sold, and operated the device that was used to do so.”

The court says this sufficient to establish that Awareness “engaged in” a violation of the Wiretap Act that makes it potentially liable in a private civil case.

The appeals panel’s ruling says nothing about Awareness’s actual liability. It merely says that the lower court erred by dismissing the claims against the company. The case now goes back to the district court.

This is just the latest high-profile legal development in an issue of increasing concern to privacy-minded consumers, and not all of them have found that companies could be held liable.

Earlier this year, the First Circuit Court of Appeals found that the makers of a service that spoofs phone numbers — allowing harassing callers to disguise their identity — should not face potential liability for the bad behavior of that app’s users, even if the app maker allegedly marketed the service as a tool for harassment.

Back in Nov. 2014, the maker of the StealthGenie app entered a guilty plea to federal charges of sale of an interception device and advertisement of a known interception device. However, that was not — like the Awareness case — a private right of action.

The Government Accountability Office looked at the debate over the legality of tracking apps and came to an inconclusive conclusion about the potential culpability of device and app-makers.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.