Is It Illegal To Use An App To Track Your Kid, Spouse, Or Employee?

There are a number of well-known apps that allow you remotely track your phone if it’s lost, or that track the movement of another device but do so with that user’s knowledge. What about those apps that let you track another phone — and maybe intercept calls and texts — without the other person having any idea?

At the request of the Senate Judiciary Committee, the Government Accountability Office looked at the marketing of 40 different tracking apps to determine how many were touting features that could violate federal laws against wiretapping, stalking, fraud, and deceptive business practices.

The GAO report [PDF] doesn’t name specific apps, but it does look at a wide range of targeted end-users for these applications — from parents who want to track their kids’ movements, to employers who want to keep tabs on workers’ whereabouts, to suspicious spouses who want to see if their loved one is loving someone else.

WE KNOW WHERE YOU ARE

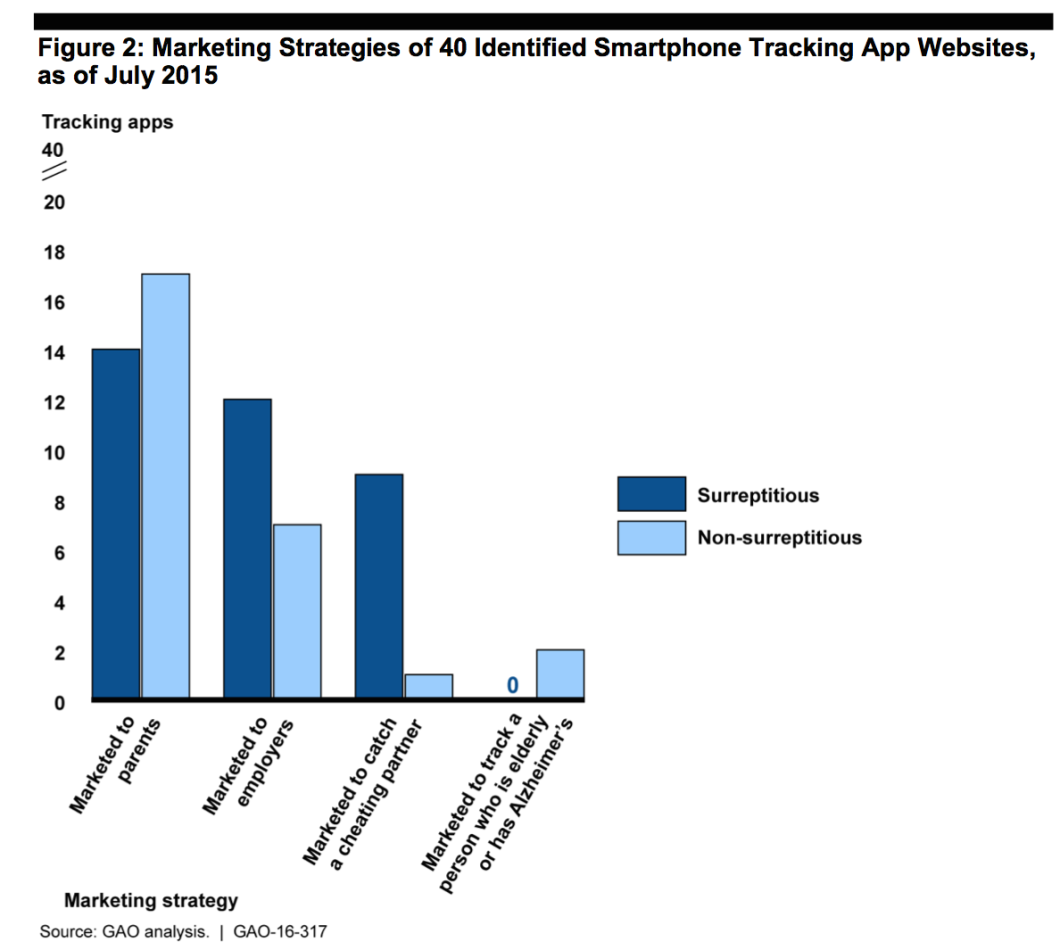

In all, about 1/3 of the apps included in the report were advertised as having a surreptitious use, meaning the person whose device is being tracked (and possibly snooped on) is unaware. As you can see from the chart below, only two categories — apps for parents to track kids, and apps for tracking elderly and Alzheimer’s patients — were mostly transparent about the tracking, while the apps sold to employers and suspicious spouses were largely under-the-radar to those being tracked:

MORE THAN JUST LOCATION

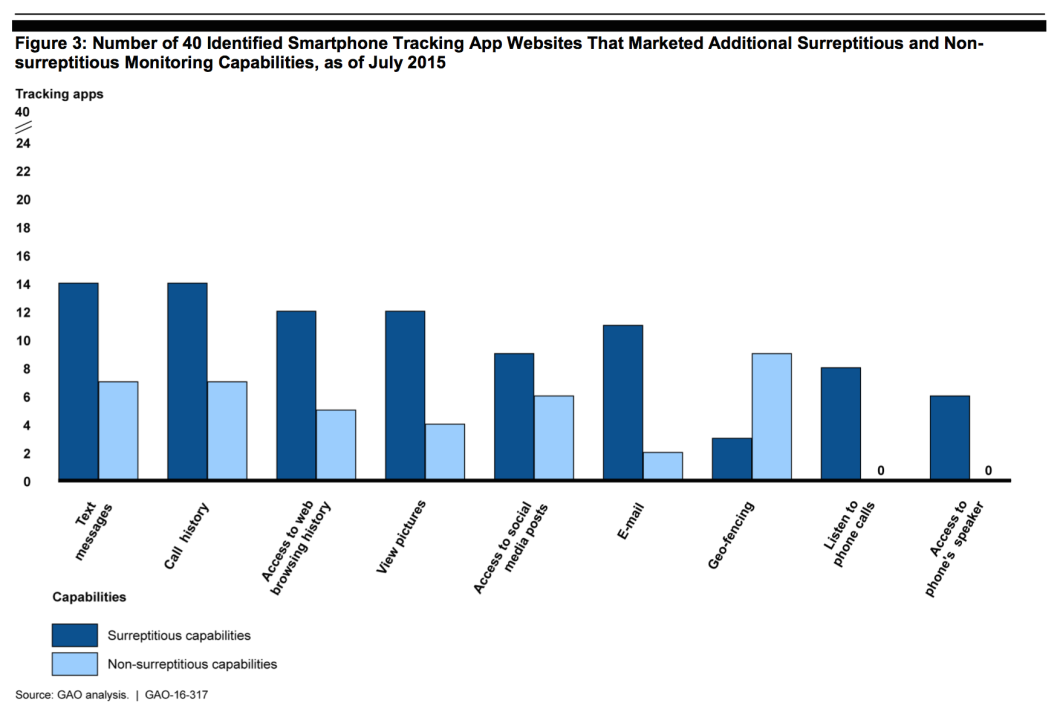

Knowing where the device is located at any given moment only tells part of the story, which is why many of the apps in the GAO report include additional features, like the ability to intercept and read emails and texts, access to the other user’s call history, photo gallery access, browser history, social media posts, record phone calls, and — creepiest of all — using the other smartphone’s speaker to listen in on conversations.

Not surprisingly, all but one of these additional snooping features was primarily marketed for surreptitious use, with some — like the ability to listen into phone calls or nearby conversations — never sold as something that would be disclosed to the target of the snooping:

DON’T DO THE THING WE SELL THIS APP TO DO

As the GAO notes, there are a number of federal civil and criminal statutes that may be in play here, depending on the extent of the snooping and the disclosures made to the person being tracked.

The federal wiretap statute prohibits the interception of wire, oral, or electronic communications unless at least one party involved consents. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act says you can’t access a protected computer (which now includes smartphones) without authorization, or that you can’t exceed what ever authorization you’ve been given. Federal anti-stalking laws prohibit the use of electronic devices for said stalking, and the good old FTC Act outlaws deceptive business practices.

All of which would explain why the GAO found that a number of these apps have clauses in their terms of use that would seem to prohibit the very things they market to users.

Of the 40 apps in the report, 13 had disclaimers that directly contradicted the marketing language used to sell the apps.

The report cites the following marketing language from one app for suspicious spouses:

-

“You would be surprised as to how much information you can find about someone just by accessing their phone. So how can you monitor cell phone activity without having to physically peak [sic] at the phone at regular intervals? Install [our product]. The software will provide you all the information you need to find out the truth about a suspected affair.”

Yet the terms for that same app attempt to negate the touted purpose of the software:

-

“[Our product] is designed for monitoring your children or employees on a smartphone you own or have proper consent to monitor (in compliance with applicable laws), and you must inform anyone who uses a device upon which the software is installed that their activity may be monitored. You should NEVER attempt to spy on a cell phone you don’t own, monitor your spouse, significant other or adult children with any cell phone monitoring product without the consent and knowledge of such persons. Doing so may be illegal, and violate local, state, and federal laws in your country and you could be subject to civil or criminal penalties. We will cooperate with authorities in investigation of any allegations of misuse.”

This two-faced marketing/legal approach is similar to the successful tactic deployed by the makers of a phone-spoofing app that was used to illegally harass a Boston-area woman. The app’s marketing included testimonials from users who had employed the spoofing in apparent violation of the law, but the app’s terms of use explicitly state that such behavior is forbidden. In the end, both a U.S. District Court and an appeals panel ruled that the app company couldn’t be held liable.

BREAKIN’ THE LAW?

While the makers of the spoofing app may have escaped legal responsibility, federal law enforcement has come down on at least one developer for producing an app that snoops on phone calls and nearby conversations.

In Nov. 2014, the maker of the StealthGenie app entered a guilty plea to sale of an interception device and advertisement of a known interception device, violations of the federal wiretapping statutes. The developer was sentenced to time served but ordered to pay a $500,000 fine.

That same month, a California woman entered guilty pleas for possessing and using StealthGenie and other spyware.

Among the groups that the GAO consulted for its report — including academics, a tech policy group, a consumer advocacy organization, domestic violence prevention groups, a wireless carrier, an app developer, and a civil liberties organization — the majority felt that using these apps surreptitiously to interrupt communications was a violation of the wiretap law.

The issue wasn’t as clear with regard to apps that only collect location data surreptitiously, noting that some federal courts have previously held that location data on its own is not “content.”

The other three laws that may apply to these apps have not yet been tested in the legal system, but the GAO notes that some stakeholders believe the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act could possibly be used to prosecute someone who installs software on another person’s smartphone. One gray area would involve a situation in which the person installing the app has a phone- or plan-sharing relationship with the person being tracked.

“In such cases, the person might be able to argue that, as the holder of the account, he or she was an authorized user and had a right to access and install an app on the phone,” writes the GAO.

The federal stalking statute could apply to those using these tracking apps to intercept another person’s emails, texts, calls, or location information, when their behavior also meets the specified intent and other criteria established in that law. However, as the GAO explains, many stalking cases are brought in state courts and stalking statutes vary from state to state. While all 50 states have laws against stalking, not all explicitly address the use of electronics and software to track victims.

“However, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 amended the federal stalking statute to permit prosecutors to pursue cyberstalking cases regardless of where the victim and offender reside,” explains the GAO. “The revised statute allows prosecutors to also focus on whether the offender used an electronic communication system capable of interstate commerce, such as a smartphone, to stalk the victim.”

While that update has allowed the DOJ to better address cyberstalking, there is still the issue of prosecuting app makers. Stalking cases primarily prosecute the alleged stalkers, not the companies that abet or encourage the bad behavior. One state prosecutor tells the GAO that it’s difficult to bring charges against app developers because many of them are overseas. Additionally, because it takes so long to put together a case against one of these app makers, the targeted company has time to change its name, its marketing strategy, or the design of the app.

Finally, the FTC Act has previously been applied to settle a case with a company that allegedly engaged in surreptitious tracking of a third party’s use of his or her computer through computer-based software, so there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t apply with regard to the same questionable practices on smartphones.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.