When You Overcharge A Harvard Business Professor $4, Don’t Blow Him Off

From the lengthy e-mail exchange between the professor and the restaurateur. (via Boston.com)

———

Boston.com has the very detailed story of how a simple case of being overcharged $4 by a Boston-area Chinese eatery resulted in a string of increasingly tense e-mails involving threats of legal and regulatory action.

It all began when the customer noticed that the prices on his receipt didn’t match the prices listed on the website for the restaurant. Each of the four items he cited was posted at $1 less than what he was charged. So he sent off an e-mail with this information to the restaurant’s owner.

Rather than offer an immediate refund of the $4 — which seems reasonable given that the total bill was well over $40 — the owner’s response was to admit that the prices listed on the website had been “out of date for quite some time.” And instead of that refund, he offered to send the customer an updated menu.

Bad idea.

The Harvard prof. alleged in his reply that the restaurant was in violation of state consumer protection laws that allow for trebled damages; and so he requested that he receive a refund of $12 be issued to his credit card or that a check for that amount be sent to his home.

Things only got worse when the restaurant offered to issue a refund, but only for $3.

“It strikes me that merely providing a refund to a single customer would be an exceptionally light sanction for the violation that has occurred,” writes the professor. “To wit, your restaurant overcharged all customers who viewed the web site and placed a telephone order… You did so knowingly, knowing tha tour web site was out of date and that consumers would see it and rely on it… You don’t seem to recognize that this is a legal matter and calls for a more thoughtful and far-reaching resolution.”

He then claims that he’s referred the situation to the relevant local authorities to “compel your restaurant to identify all consumers affected and to provide refunds to all of them.”

The professor agreed to accept whatever refund was offered, but “without prejudice to my rights as provided by law,” meaning he wasn’t giving up any future legal claim he might have for damages.

In response, the restaurant owner writes that he will indeed refund the $12, but only after he’s been advised that this is the proper thing to do by the authorities. He also promises to have the site’s menu prices fixed.

But then a subsequent e-mail explains that, after getting legal advice from a third party, the restaurant will not be honoring that refund request as “we are covered and protected” by language on the site that says pricing may vary by location.

To which the professor replies that he doesn’t know of any disclaimer that can allow a company to knowingly charge higher-than-published prices for an extended period of time.

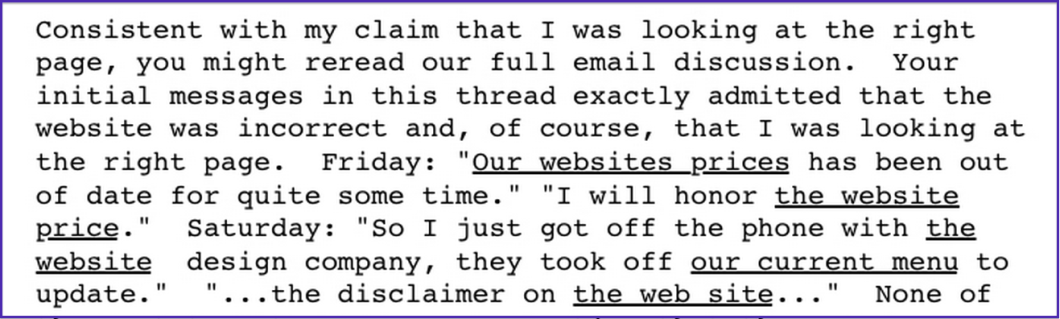

There is then some dispute about whether or not there are multiple menus for different locations and which one the professor was using for his pricing comparison.

And then the restaurant owner asked a question he shouldn’t have.

“You seem like a smart man, but is this really worth your time?”

“You’re right that I have better things to do,” responds the professor. “If you had responded appropriately to my initial message — providing the refund I requested with a genuine and forthright apology — that could have been the end of it… Instead, you’re making up excuses such as the remarkable but plainly false suggestion that I was on the wrong web site. The more you try to claim your restaurant was not at fault, the more determined I am to seek a greater sanction against you.”

Systematic overcharging — whether intentional or inadvertent — can be a serious problem for a small business. Here in the Philadelphia area, a South Jersey pizzeria was recently accused of overcharging customers who used prepaid cards on a daily basis for several months.

But first you have to get people to listen to you. The Harvard prof says he’s alerted the local authorities about his dispute with the restaurant but doubts they’ll take action. He could pursue a civil action on behalf of all the restaurant’s customers who ordered based on the prices listed on the website but says he hasn’t decided whether to go that route.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.