You don’t know their names, but you see them everywhere: countless shades of reds, greens, blues, grays, tans, taupes, whites, off-whites, charcoals, blacks, gold and silver. Really what you’re seeing is Vanilla Shake, Tahitian Pearl and Torched Penny. Cars are everywhere, and so are the colors they’re cruising around in, their own distinctive skins. Paint is one of the most important design aspects parts of a car — the right paint job can mean the difference between luxury and sport utility, can turn Grandpa’s jalopy into a teen dream machine, and forever change a car from a vehicle you use to get around to a statement on free love and drugs.

This came up in the Consumerist newsroom we call a conference call — everyone remembers that one car with the special paint color — Polynesian Green, Clover Green Pearl, Deep Maroon 347 — perhaps more than any other aspect of the beloved former ride.

But when you look around on the road and in your neighbors’ driveways, not everyone is driving in the technicolor lane. It feels more like the Model T days, of which Henry Ford wrote in his autobiography: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black” (more about that later).

In fact, if it feels like we’ve returned to our grayscale roots, we have: Last year for example, the most popular car color in North America was white, reports Forbes, followed by black, gray and silver.

And yet in that same article, Forbes discusses how popular a color is doesn’t mean it’s necessarily the best value, noting how a yellow car bought new will have a higher resale value down the road — pun completetly intended — than your more everyday tones.

As it turns out, during the recent recession, consumers were a bit shy of flashy things and tended to play it safe when and if they took the big step of buying a new car, and that trend has persisted over the years. Meaning the likelihood of a flood of yellow cars on the market is not great, hence, the rarer it is, the higher price tag it can command.

This effect also works for green cars (Polynesian Green!) and orange (Tangerine Scream!) as well as teal (Just Teal [not a real color but should be]).

The Bold And Bright Early Days

So now that we know the reason for popular car colors now, we wanted to figure out why, if perhaps trends are always or often tied to current events like a recession or depression.

Back to Henry Ford and his “any color as long as it’s black” statement: To quote Jerry Seinfeld, “What was the deal?” Was it because everyone was just in a a really cranky mood and just didn’t feel like happy colors?

Not really — and as it turns out, there were some pretty spectacular car colors around the turn of the century, explains Gundula Tutt, an automotive color historian, conservationist and restorer living in Vörstetten, Germany. Her doctoral thesis is titled “History, development, materials and application of automobile coatings in the first half of the 20th century,” and she’s a member of the Society of Automotive Historians. So she knows her stuff, it’s safe to say.

Back around 1900, Tutt says, cars were basically motorized carriages and thus, painting methods were derived from the oil-based coating formulations used for traditional horse drawn carriages.

It was a complicated, expensive procedure to to apply the paint, and the drying time took several weeks. The color was luxurious, providing for brilliant paint jobs, but the paints couldn’t stand up to time and would end up turning yellow. There was no binding medium, Tutt says, so every time a color would fade or yellow, it’d have to be repainted. It gets expensive.

That long, expensive process is what prompted Ford to develop asphalt-based baked enamels for his cars — dark colors lasted longer, it fit in with the assembly line process and didn’t take as long to dry.

“This marked a big step for industrial mass production of the Model T and other low cost automobiles, since it synchronized the painting action to the frequency of the assembly line,” Tutt writes in her thesis.

In other words, this change in how cars were painted might seem simple now, but think about it this way — without these kinds of innovations, cars would’ve proven too expensive for most people and thus, a whole lot more of us might be on bikes.

The asphalt enamel method wasn’t without its downsides, however, as it did require a large amount of space with nary a stray bit of lint or hair to mar an otherwise perfect paint job.

The painters would even paint naked, Tutt added with a chuckle.

“I think I would have liked to see that!” she said, and was immediately agreed with by yours truly.

Peacetime Is Paint Time

More innovations followed after World War I ended, when the world was at peace again and the automotive industry could turn its attention from tanks and wartime vehicles to civilian cars.

New methods using Chinese wood oil (or tung oil as it’s sometimes known) could be sprayed or painted on, and made for much faster drying times in 1918, at about one third the time compared to the oil-based paints, Tutt says. Drying tunnel ovens shortened time even more, and were worked into conveyor systems already in place on assembly lines.

And to add to the bonus of a speedy dry job, these “spar-varnishes” and “spar-enamels,” as they were known then, allowed for colors for the first time. Like Dorothy stepping out of the house into Oz, manufacturers started to produce brilliant colors.

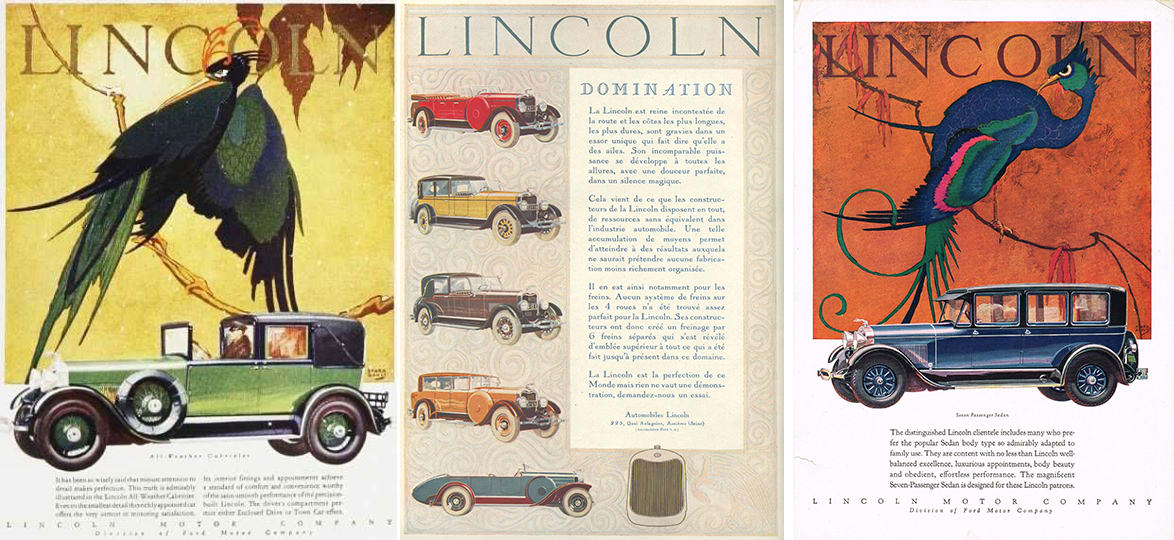

The early 1920s saw brilliant shades — the colors of the time were exotic, Tutt explains, with two, three and even four colors ont he same car, as well as painted birds and butterflies on some Lincoln models.

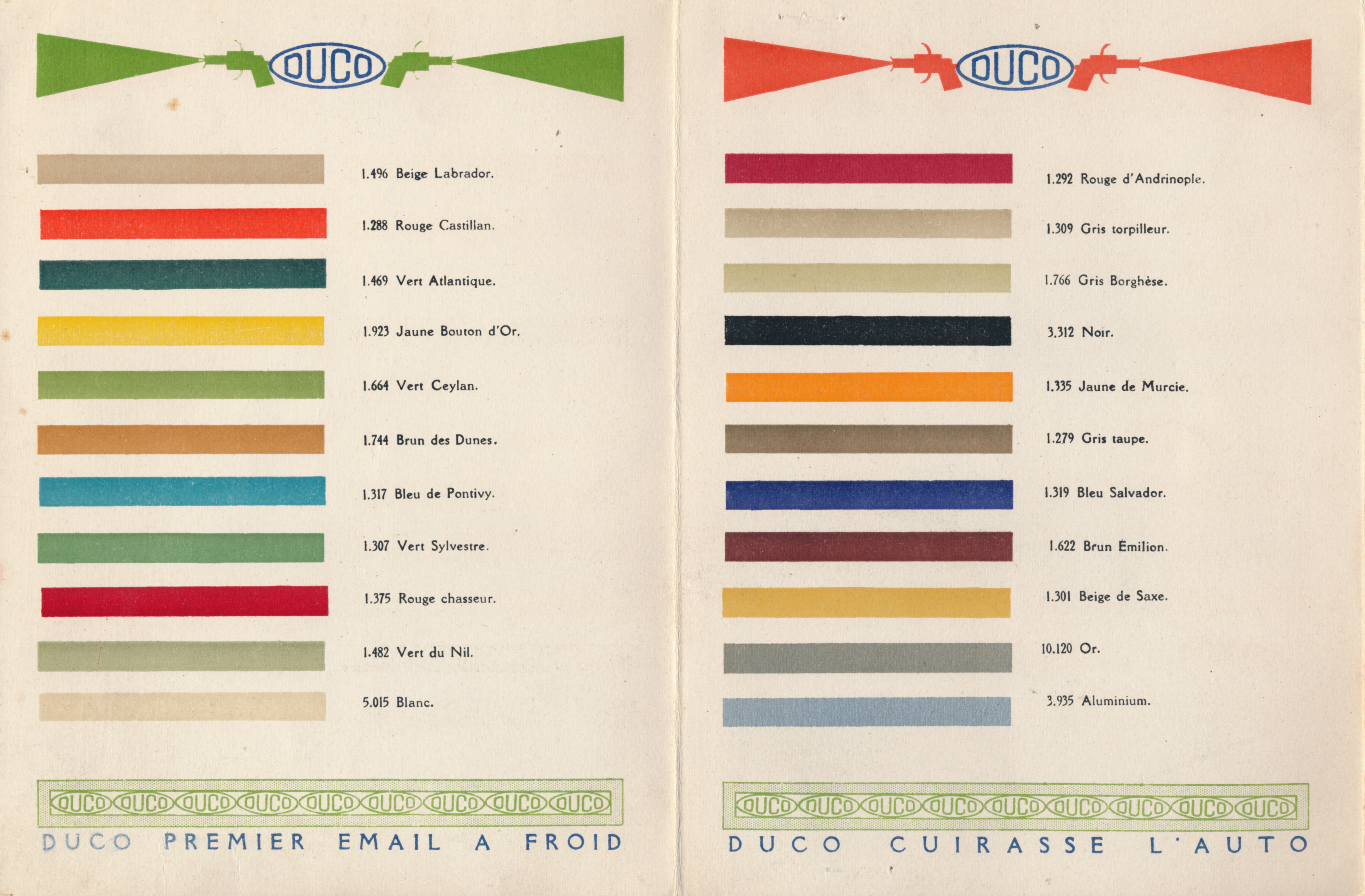

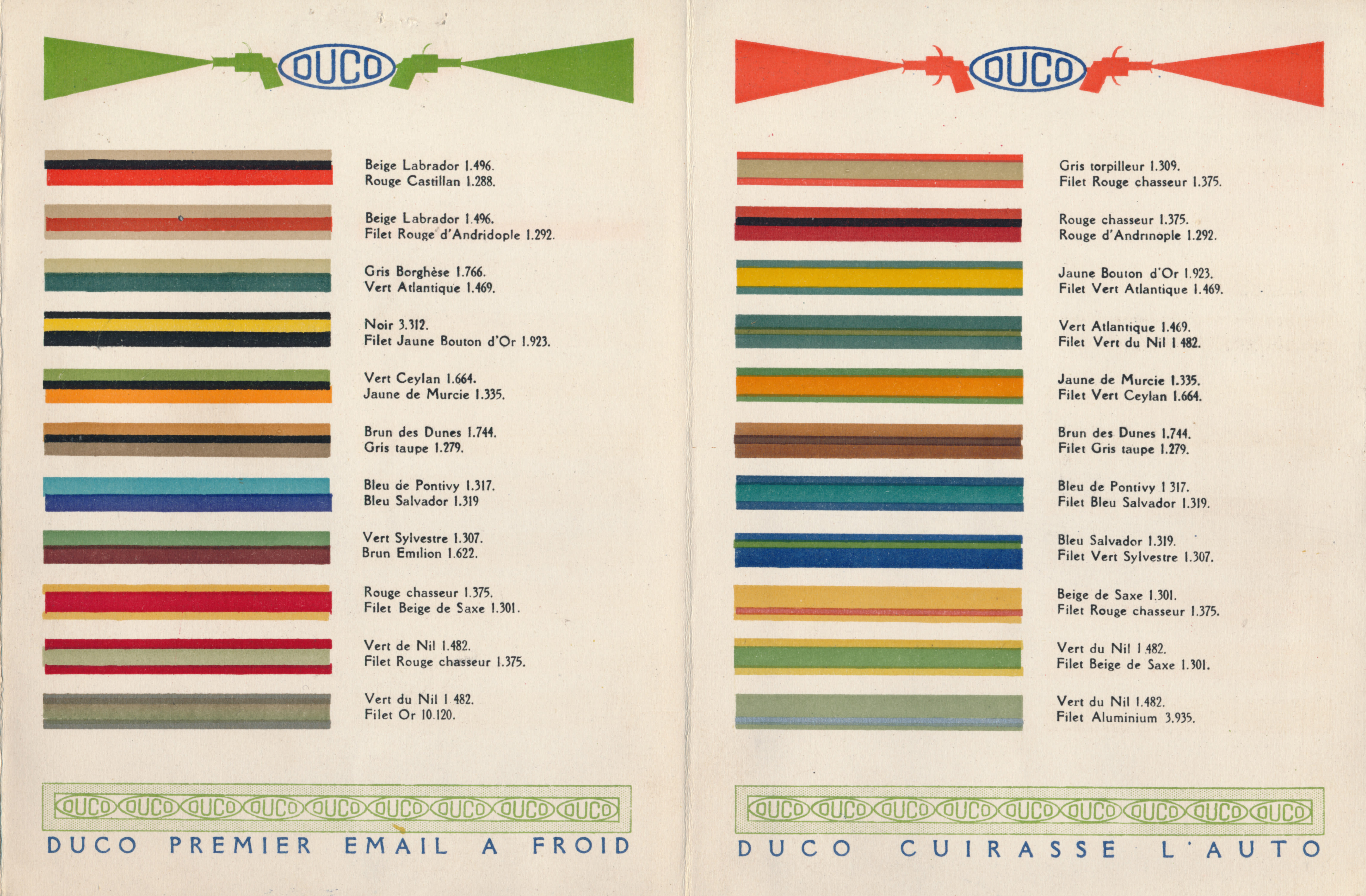

Fast forward to the 1920s, when General Motors worked with the Dupont chemical company to create something known as pyroxylin, a substance that could be mixed with pigments to come up with new automobile coatings in a rainbow of colors, was more durable than previous pigments, and even better — could dry in minutes instead of hours.

In 1923, the new Duco paint (as it was called) pyroxylin colors debuted at the New York Auto Show on GM’s Oakland Motor Car Company’s cars, known as the “True Blue Oakland Sixes.”

“Alfred P. Sloan, who had become GM president in May 1923, believed that consumers buying lower-priced cars would appreciate a range of color choices, particularly if the paints lasted,” notes the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

All seven touring cars were painted with Duco, each receiving two different shades of blue and accented with racing stripes of red or orange.

“Blue is a complicated color,” adds Tutt,” because it yellowed easily before. Now there was much less yellowing and upkeep, it was a cheaper, garageless car,” which was nice for consumers, as you could have a car without the bothersome expensive of having a garage.

An attractive product more people could afford? We were off — color was the new thing.

“These colors were used to do stripings and detailed decoration on vehicles shortly after 1925 (pyroxilin base), often combining two bright colors on the body with another contrasting striping color,” says Tutt.

Try telling that to Henry Ford, however, as Tutt says he resisted the change because of the elaborate process he already had built for painting his cars. In fact, Tutt says, any Model Ts that were repainted in a different color other than black would have their warranties voided.

It was too late, now that the colors had been turned on, they couldn’t be turned off. Dorothy, meet Oz.

Let The Color Revolution Begin

Around that time, GM started a color advisory service, sending people to watch the shows in Paris, ask people what they’d like and develop new color systems, Tutt says. Such a service was very much at the pulse of consumerism, as the industry tried to figure out what people would buy other than black.

There was a bit of a pause in the color parade when the market crashed in 1929, Tutt notes — colors got dimmer, more depressing, in somber greens and grays. And when cars were colorful, fenders were often painted black in a melding of the practical and the aesthetically pleasing: Dinged fenders could be easily and cheaply painted with asphalt paint, saving on repairs.

Despite the downtrodden economic times, the 1930s saw the addition of metallic paints, which were first made from actual fish scales and reserved only for the very rich.

It would’ve taken 40,000 herring to make one kilo of paint, Tutt says, but they’d give paints a mother of pearl sheen that could show off the curved forms of the cars of that day.

But for most folks, expensive fish scale paint wasn’t a practical possibility. American paint companies used aluminum flakes in their metallics, which were much cheaper than fish scales. Color names still paid homage to their fishy predecessors, with colors like Fish Silver Blue.

The 1930s and 1940s saw a rise of chrome trim and single-color cars, Tutt says, especially after World War II when new innovations brought us sun-resisting clear coats for metallics to help them stay bright and not yellow. These coats helped protect bright shades from fading, another pro for consumers who wanted their cars to last.

Advisory panels became de rigueur for manufacturers after WWII, Tutt says, with companies once again asking customers what they wanted for their vehicles as paint methods continued to develop.

By the time the 1950s hit, consumption was a patriotic duty.

Car colors and popular culture had hopped in bed together and from now on were closely married — just look at Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters touring America in the 1960s in Further, a hippie bus in every sense of the word in not only its passengers but the wild, bright splashes of color decorating it.

Other world events beyond the fashion shows and celebrities of the time affected car colors as well, Chris Wardlaw, who previously worked in the automobile industry with previously worked for Vehix.com, J.D. Power and Associates and Autobytes, tells Consumerist.

“In the 1970s there was the gas crisis of the early 70s, so I think there was a more ecological mindset among Americans and we started to see a lot of earth tones out there, especially brown,” Wardlaw says.

He adds that the one exception was 1976, the year of the Bicentennial, the year of the decade when the most popular colors were red, white and blue (separately, not combined on one car in some kind of flag thing).

Why Are We All So Boring Now?

I don’t think there’s one clear reason why we’ve been stuck on shades of gray, white and neutrals in the 2000s — but a quick glance at popular gadgets of our day, devices that play a big part in our everyday lives today. It makes sense, then, if you like your iPod (or later iPhone) in white, maybe you want your car in that color, too. Like the silvery gray of your HTC One? It could show up in your car too.

White’s comeback can partly be attributed to Apple, explains Barb Whalen, designer manager, color and materials at Ford Motor Company. She says that though you might think white is just a boring color that’s never going to change, Apple “helped that trend move on.”

After all, white isn’t just white — there are luxury whites with tricoat paint jobs, and then there are the simpler, sportier whites.

Because of the tried-and-true trio of white, silver/gray and black, many manufacturers will use those basic colors on more than one model, because why mess with a good thing?

“There’s a group of customers that always just goes for those basic colors, and that’s what they’re going to come back to,” Whalen says. “But there are definitely customers out there who want to be on trend that strive for something different. When they lease their vehicle for two years they want to come back with the latest and greatest color.”

But on that note, not every wild and craaaazy color is going to work on every vehicle. Some are niche-specific, Whalen explained to Consumerist.

“Certain colors are appropriate for certain vehicles,” she says. “For example, the Green Envy you would see on a Mustang, you would never put that on an F150. It would just be kind of comical, I think.

“But a Mustang customer loves that bright green on that vehicle and it’s appropriate, it’s inspired and it’s sporty and there’s a customer out there that wants that attention, that wants to say, “Hey, look at me and look at my car.”

We wondered about those names — what’s it like to come up with those unique monikers?

Car manufacturers these days have taken color advisory boards of the past and started employing color development teams, which dedicated to coming up with that name you’ll always remember, or the one you’ll forget but appreciate that it wasn’t just “gray.”

“We have a lot of fun with naming colors,” Whalen says.

The team comes up with a color first, one that’s inspired by design and trend information from Ford’s suppliers, and then that color, purple, perhaps might trigger an image of something, say, of Tahiti. And there you have it, Tahitian Pearl.

As to why companies think we want Tahitian Pearl, Whalen says that at Ford, they don’t ask the customers what they’d prefer, because colors are developed for years ahead of time. As trends change every couple of years, so will consumer preferences.

“Color preferences are personal and if you’re asking a customer that will ever buy a black car if they’re going to ever enjoy a Bronze Fire or a Deep Impact Blue vehicle, their preference is always going to be black, so don’t ask them.”

Instead, Whalen and her team work with suppliers to gather research and look at trends to develop the company’s car palette. Core colors like (sigh) white, silver/gray and black “don’t change a whole heck of a lot throughout the years” barring any change in technology.

“The colors we tend to change more often are trend colors, and those might change every couple of years,” Whalen says.

Are We Totally Over The Rainbow Or Is The Future Going To Be Bright Again?

Whalen agrees that the recession dampened car buyers’ appetite for bright colors, saying consumers were a bit “leery” for a little while, leading to the rise of the neutral set. But the future is bright, she thinks.

“We’re optimistic” about color’s comeback she says, adding, “It was only four years ago that neutrals and whites really were the most popular, you would rarely look in a parking lot and see anything other than those colors,” and now, colors are coming back to those lots.

There are other trends making a splash in the car world these days, Christian Wardlaw points out — including the “stealth” trend that employs matte paint colors and dark windows.

“Among car enthusiasts, especially younger male car enthusiasts, matte has become, I wouldn’t say it was a status symbol but it became popular because it’s different. It lacks luster, so it’s more stealthy.”

Will we ever get a future of made-to-order customizable colors for our cars in any one of say, hundreds of options? Not likely, Wardlaw thinks, mostly because of the associated costs with factory-applied paint. But much like that phone cover you can swap out at whim, there’s always the option to have a temporary wrap applied to a car, like the local bakery/taco place/dry cleaners did with their delivery SUV.

I’m Feeling Crazy — Should I Buy A Car In A Wild And Wacky Color?

Different strokes for different folks — so yes, if you really love that yellow bit of canary-inspired sporty sunshine, go for it, but keep in mind that not all weird colors are rare. There’s a reason there aren’t always a lot of yellow cars, Wardlaw thinks.

“A lot of companies will only offer [colors] that they know will sell in big numbers because they’re not going to take the risk,” he says.

Whether or not you take that risk, it’s up to you. But at least you don’t have to order it in black, if you don’t want to.

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared on Consumerist.