Overdraft Fees Are Trapping Consumers On Social Security In A Cycle Of Debt

The Center For Responsible Lending has put together a report that examines the disastrous effect of overdraft fees on Americans who depend on Social Security for all or part of their income. Despite the fact that they’ve had checking accounts all their lives (and presumably know what they’re doing), each year older Americans pay 4.5 billion dollars in overdraft fees– and on average they actually pay more in fees than they receive in credit when the overdraft is triggered by a debit card transaction.

The average debit card transaction triggering an overdraft is for a $26 purchase. For this transaction,the bank makes an average loan of $19.95, or the amount overdrafted, and charges an average fee of $33 for each incident. This amounts to an average of $1.65 in fees per dollar borrowed. Thus, older adults pay more in fees than they receive in credit for the average debit card purchase triggering an overdraft.

Since Social Security payments are disbursed only once a month, a consumer on Social Security can rack up substantial daily balance fees waiting for her next check– trapping her in a cycle of overdraft fees and debt that’s eerily similar to a payday loan scenario. If the consumers on Social Security were instead given a line of credit they could avoid this cycle of debt.

The Center for Responsible Lending illustrates this difference by sharing the story of Mary, a real consumer entirely dependent on Social Security:

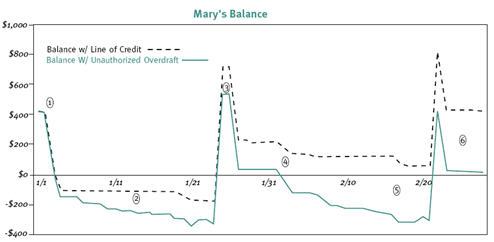

Mary begins the year 2006 with $420.56 in her checking account, held at a large national bank. She makes a $380 ATM withdrawal and several smaller point-of-sale purchases on January 3, comes up short, and is overdrawn by January 4. She incurs a $34 overdraft fee for the initial overdraft. After two more purchases, and two more overdraft fees, she finds herself almost $200 below zero on January 9. For the next eleven days, Mary doesn’t spend any money from her checking account, but her checking account loses money, nonetheless. Her bank charges her a fee of $7 a day because of her ongoing negative balance. By the time a scheduled electronic withdrawal is made to pay a bill for $32.38 on January 20, Mary’s account is overdrawn by more than $300, and the bank rejects the transaction. Her bill goes unpaid, although the bank continues to charge daily negative-balance fees.

Finally, on January 25, Mary receives her monthly Social Security check of $904. However, her account is already $335 overdrawn and she still has an additional $500 in expenses for the month. Once these payments are made, Mary only has $31.09 left to live on until her next Social Security check comes in late February. Because of this, Mary almost immediately has a negative checking account balance again, once she makes three small ($20 or less) purchases on February 1. Over the next two days, Mary incurs two overdraft fees because of these purchases and conducts another transaction for $50, which also results in an overdraft.

Mary does not make any more purchases between February 8 and February 17. However, the bank again continues to charge her a fee of $7 a day because of her ongoing negative balance. On February 18, an automatic bill payment causes Mary’s account to go even farther into the red—a transaction that the bank approves even though her account is already below zero and she cannot even repay the $7 daily negative balance fee. Once Mary’s account dips to $314.91 below zero, the bank finally begins to refuse additional transactions, rejecting a utility bill for another month. The $7 daily negative balance fees continue to be assessed through February 21.

Finally, on February 22, Mary’s Social Security check comes in, and the account balance ends up above $400 once the bank subtracts the overdraft fees. Unfortunately, because Mary still has to pay her end of the month expenses totaling about $410, she is left with only $18.48 to tide her over until the end of March. This meager sum—even less than the $31.09 she had to make ends meet after being charged for overdrafts in February—virtually guarantees that Mary will continue to remain trapped in a cycle of accumulating overdraft fees month after month. In January and February, Mary paid $448 in overdraft fees in return for receiving $210.25 in credit from her bank, and was forced to live on $20 from a Social Security check of nearly $1,000. If Mary’s bank had instead offered her an 18 percent APR line of credit to cover overdrafts, she would have only paid about $1 in total fees for her overdrafts.

As you can see in the graph above, if Mary would have been offered a line of credit, she would have ended up with $420 at the end of two months and would have been able to pay her utility bills.

The Center for Responsible Lending is working to stop banks from being able to automatically drain Social Security funds from checking accounts, but the important takeaway for us is this: It’s important that you or your family consider switching to a bank that allows you to link a savings account or offers a less expensive line of credit so that you can avoid these fees — particularly if you or your loved ones are retired and on a fixed income. There will likely be a fee for this service, but when you consider the alternative, it may be a wise choice.

Here’s some basic information about overdraft protection from Bankrate. You can also compare accounts and overdraft fees with Bankrate’s checking account finder.

Shredded SecurityOverdraft practices drain fees from older Americans (PDF) [Center For Responsible Lending via CL&P Blog]

(Photo: michael.kinne )

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.