It’s right there, somewhere. Buried deep in a menu under “legal” in an app, or lurking somewhere in the footer of a website that never seems to stop adding content while you scroll. Each of us encounters dozens of them every day and yet most of us never give any thought to them. It is, of course, the privacy policy.

There is an implicit promise apparent in the phrase “privacy policy,” an indication that a business is going to respect your privacy — or, at the very least, that you have some privacy. It’s right there in the name, so “privacy” must be involved somewhere, right? Somehow?

The policies are definitely about privacy, yes, so it is involved… it’s just not actually guaranteed.

Nearly every website, service, app, and online business has a privacy policy. Sometimes it’s right there, linked from a homepage. Sometimes it’s a few paragraphs buried thousands of words into a user agreement you’ll likely never read.

In spite of their prevalence, most of us don’t know what these policies say, do, or are — and misconceptions abound.

This is our attempt to clear up some of those myths, like…

Myth #1: Federal law requires all online businesses to have a privacy policy

Reality: FALSE

There is no global right to privacy, online or off, under U.S. law (other nations’ laws vary), nor is there a universal legal requirement that privacy policies be written or posted.

You can feel the “but” coming though, right?

Yes, there’s a but: there are several specific industries and types of data that, under federal law, do require a certain kind of handling or disclosure, as well as some relevant state laws — and that patchwork quilt of laws and regulations is pretty widespread.

Health care providers, for example, are covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). However, not all entities that might hold sensitive health data are covered by or required to adhere to the HIPAA rules, which is becoming a problem as the world of personalized and wearable health tech expands.

Another type of highly-protected data involves your money. There are two important laws out there dealing with businesses that handle consumers’ financial info, and the privacy parts of both are enforced by the Federal Trade Commission.

One is the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which was first passed in 1970 and has been updated and amended a few times in the 45 years since. The other is the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which changed a number of banking rules.

These are two complicated pieces of legislation, but businesses that have data about your money are often covered under one or the other. The FCRA generally applies to consumer reporting agencies, and the the GLBA covers any business that’s “significantly engaged” with financial activity — a larger pool of businesses than you might think.

The FTC has guides explaining which businesses need to adhere to the FCRA or to Gramm-Leach-Bliley, but both are full of lots of conditional statements and very important details.

In short, these are the rules that cover your banking transactions, your Social Security number, your credit history, and even information that relates to your “character, reputation, or personal characteristics,” depending on who is gathering it and what it’s being used for.

There are also other, narrower laws and regulations applying to even more niches of data. Cable and telecoms’ uses of consumer data are regulated by the Cable Act and Telecommunications Act, for example, and enforced by the FCC.

Federal government sites and services have their own regulations and disclosure rules. And then there’s a whole separate world of privacy, COPPA, that applies to the data of children under age 13.

Beyond all that, though, there is also one state-level law that has had a large impact. California passed its Online Privacy Protection Act in 2003, and that law requires anyone who operates a website that California residents can access or use to “conspicuously post its privacy policy.”

Because of the way the Internet works, the list of websites accessible to California residents is functionally the same as a list of all websites, and so in a sense that California law has become a de facto national policy.

Myth #2: Privacy policies guarantee that my data will be kept private

Reality: FALSE

A privacy policy is a document disclosing what information a business gathers and what they do with it, not a guarantee that your data will be treated with any particular sensitivity or regard.

In a general sense, most privacy policies are telling you three things:

- What data is this business collecting about you and your actions?

- How and why (for what uses) does the company collect that data?

- With whom, and under what circumstances, does the company share that data?

For most online businesses, those disclosures are going to be about how they collect, use, and share your interactions with them — things like your web browsing and purchase histories — with third-party data brokers and marketers who can use this info to try to sell you more stuff.

They may also include descriptions of which sharing you can or can’t opt out of, and explanations of how to do that.

This is easier to understand with examples.

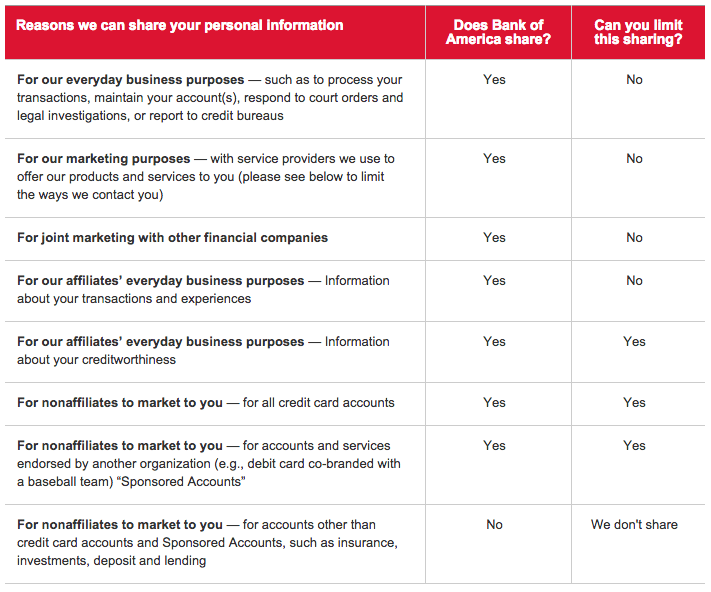

Take Bank of America’s consumer privacy notice. As a bank, they’re limited under the laws we just discussed. Even so, though, the bank is quite clear that it will share whatever data it can share with third-party marketers. And BofA tells you quite clearly which kind of marketing you can or cannot opt out of.

Most policies, though, strive to be at once both accurate and vague. Take Kohl’s, for example, a brick and mortar retailer with a sizable online presence. And, like many other retailers who exist in both the on- and offline spheres, Kohl’s has a privacy policy that tries to cover all the bases.

Under “types of information we collect,” Kohl’s says:

“We collect your information, including certain personal information, such as your name, address, phone number, email address, location information, and more, from various sources, including:

- Information collected when you interact with us, such as during transactions, completion of forms, registration or surveys, and through your participation in our marketing incentives and programs;

- Information from other sources, such as companies that help us to update our records; and

- Information automatically collected when you visit or use our Site or view our online ads, such as via cookies and device information, and in Stores, such as through your use of our Wi-Fi Services.”

“Information from other sources” is a broad category that covers Kohl’s in the physical and virtual worlds.

Likewise, under the heading “how we share this information,” Kohl’s says it shares with “companies that provide support services to us and our business partners.” That category of “support services” and “business partners” is also very broad, and could effectively encompass any company that does business with Kohl’s.

As for that language…

Myth #3: Privacy policies always have to be in incomprehensible legalese

Reality: FALSE

Granted, many privacy policies are so positively impenetrable that you could go cross-eyed in about ten seconds flat trying to parse them, but they don’t necessarily have to be.

In fact, there has been a consumer-friendly trend over the past few years of trying to make privacy policies almost comprehensible to the casual reader. This trend toward readability has picked up so much steam that even the Wall Street Journal has noticed it.

(NOTE: Our parent company, Consumer Reports, tells us that they are working to improve the readability of our own policies.)

Perhaps surprisingly, Facebook is one of the exemplars in this move toward increased coherence. While the company might have its fingers in basically every aspect of the online world, its privacy policy is (now) clear and explicit about what data the site collects and how it is used.

The layout, too, is meant to be readable, using plain English headers, white space, and color-coding to make sure that you don’t completely glaze over between learning that data includes not only things you do but things everyone else you know does, and learning the long list of entities it can be shared with.

Crowdfunding platform Kickstarter likewise has a plain-English policy, as do Pinterest and Spotify. But there’s a reason that even the policies that try hard to be accessible still use very, very carefully crafted, lawyer-friendly language. It’s because…

Myth #4: A business must adhere to the terms of their posted privacy policy, whatever it says

Reality: TRUE

This last part is where companies get in trouble: if you say you’re going to do a thing, you are beholden to that thing.

Regardless of whether you are required under any specific law to protect any data in a certain way or post a privacy policy, if you do post one, you must adhere to it.

It’s the FTC’s job to protect consumers from false, misleading, or deceptive advertising or promises, and failing to adhere to your statements about privacy counts.

For example, if you happen to be an app that promises that content vanishes in to the ether ten seconds after someone views it, you actually need to make sure that content is not accessible (and stealable) more than ten seconds after someone views it.

That’s what got Snapchat in trouble with the FTC back in 2014: the company made claims about privacy that the feds found were just not true. Messages did not, as claimed, vanish completely after being viewed. Users did not, as claimed, always receive a notice when someone permanently saved their content. And users were not, as claimed, connected only to their friends but sometimes, accidentally, to complete strangers.

In a statement at the time of the settlement, FTC chair Edith Ramirez made the agency’s position clear: “If a company markets privacy and security as key selling points in pitching its service to consumers, it is critical that it keep those promises.” She added, “Any company that makes misrepresentations to consumers about its privacy and security practices risks FTC action.”

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared on Consumerist.