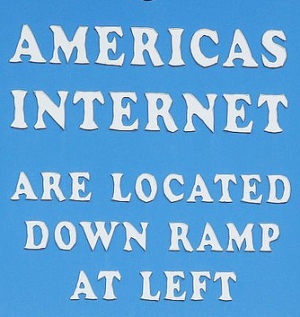

FCC Could Use Mergers To Force Net Neutrality, But Shouldn’t Image courtesy of (Steve)

(Steve)

The Problem

Earlier this year, a federal appeals court struck down the core of the 2010 neutrality rules — which prohibited Internet service providers from blocking, degrading, or prioritizing the content they carry to and from end-users — because it ruled the FCC didn’t have the correct authority to regulate broadband Internet in this way.

This left the FCC with two options: reclassify broadband as a telecommunications service (as opposed to its current classification as an information service), giving the commission to enforce neutrality, or come up with a compromise that may pass legal muster under the existing classifications. Since reclassification would likely result in another protracted legal battle, FCC Chair Tom Wheeler has come up with a controversial compromise that would allow ISPs to seek exceptions to neutrality guidelines in order to charge more for so-called “fast lanes.”

The Cheap Solution

Even though the old neutrality rules now lay dead and bloodied on the courtroom floor, Comcast is still legally obliged to abide by them through 2018 as a condition of its merger with NBC Universal. Now that Comcast is trying to swallow Time Warner Cable, it has already pledged that acquired TWC Internet customers would similarly benefit from this compliance obligation.

And when AT&T announced it was buying DirecTV, it volunteered to abide by those stricter 2010 rules if the merger was approved. The companies have pledged to follow these guidelines even if Wheeler’s less strict version ends up being enacted.

It would be incredibly easy — and expected — for the FCC to use its merger approval leverage to make Comcast and TWC pledge to extend neutrality beyond 2018, and to talk AT&T/DirecTV into a long-term promise to follow the 2010 rules. As much as these companies would love to plunder the pockets of large content providers, they aren’t going to risk mammoth, market-changing mergers on the possibility of some extra revenue, especially not when the paid-peering deals like the arrangement between Comcast and Netflix shows there are ways to squeeze money from content companies without violating the neutrality rules.

Don’t Give Into Temptation

Okay, so it looks like the FCC would be able nudge pay-TV companies with a combined audience of around 50 million people into decent net neutrality agreements. What could possibly be wrong about that?

Lots of things.

“You got two-thirds of the industry in front of you potentially by the end of the summer, which is enormously tempting to try to create an industry structure around that,” Harold Feld of Public Knowledge explains to the Wall Street Journal. “But it’s not as easy as it looks. You’ll have a bunch of different companies, many of whom may not be willing to go that far.”

Partial Victories Are For Losers

You may look at the 50 million or so consumers that would be affected by the FCC pushing the 2010 neutrality rules on both the Comcast/TWC and AT&T/DirecTV mergers and think that’s a pretty good chunk of the country that would benefit from having those guidelines enforced. But the actual number is significantly less than that.

AT&T’s broadband business is growing but still small, and while DirecTV has some 20 million pay-TV customers, almost all of them get their Internet access from a local cable or telephone company. Now, some of those subscribers are also Comcast/TWC customers, so they’d be included, but all the DirecTV subscribers who rely on Verizon, Cablevision, Charter, Cox, RCN or any of the other ISPs that aren’t currently trying to merge with each other would not benefit from the neutrality that AT&T is promising.

And of course all of the customers of those other ISPs would be getting their broadband from companies that will be operating under whatever regulations the FCC ultimately settles on.

The Expiration Date

The biggest problem with the FCC possibly using its merger-related leverage is that, unlike reclassifying broadband, it will only be for a limited time. While all of these companies appear to be willing to tack on a few more years of the 2010 neutrality rules, we can’t imagine that any of them would be willing to sign something permanent or any condition that locks them into these rules for more than a handful of years.

And so any deal made by the FCC would have an expiration date on it, which would be fine if the Internet were a passing fad.

Chairman Wheeler has previously stated that he believes it’s more important to craft “an enforceable rule” than it is to “debate over our legal authority that has so far produced nothing of permanence for the Internet,” which implies that he is fine with doing the right-now thing instead of the right thing.

The issue of neutrality will not be resolved by kicking the can further down the road, hoping that the FCC can continue to occasionally strong-arm ISPs into committing to strict neutrality guidelines.

Reclassifying broadband provides an immediate solution by giving the FCC the authority to regulate ISPs as the vital pieces of infrastructure they have become. It also allows for flexibility in the long run, allowing the commission to tweak those regulations as the Internet continues to grow out of its current adolescent stage.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.