Don’t Believe Comcast… Mobile Broadband Is Not Competition For Cable Internet Image courtesy of (Alan Rappa)

Merger-mad Comcast and Time Warner Cable would have you believe that they are in direct competition with mobile broadband. And Verizon has successfully misled the state of New Jersey into thinking that accessing the web on your phone is the same as having a high-speed data connection to your home. Both of these conceits may someday be accurate, but the reality of the here-and-now is quite different.

The growth of mobile connectivity and the use of mobile devices, phones and tablets both, is indeed the great and growing tech trend of the decade. Although we’re not there yet, it’s not hard to imagine a time in five, ten, or 20 years when mobile broadband will in fact be the preferred and dominant way we all connect to each other. So what are the obstacles standing between then and now?

WHY NOT NOW?

The would-be all-mobile user of 2014 faces three key challenges:

1. Reliability: Connecting to a network, and staying connected to it, can be a challenge even (and especially) in the most moneyed and densely-populated parts of the country. Verizon has admitted that it has had to occasionally downgrade LTE customers to previous-generation 3G service because of network congestion.

2. Speed: Mobile broadband at its fastest is still slower than a large percentage of traditional broadband.

3. Cost: Although prices aren’t quite as high as they used to be, wireless consumers still pay an extraordinary amount of money for every megabyte of mobile data they use on wireless when compared to standard rates for home broadband.

Together, those factors add up to an environment where even the current best in modern mobile network tech, 4G LTE, isn’t quite good enough to replace traditional broadband for most folks.

NETWORK SPEED & REACH

In the United States, 58% of adults own smartphones — and probably all of them have, at least once, run into some kind of hiccup using mobile data.

Some large, bandwidth-intensive apps will only update on WiFi and won’t connect at all over 4G. Sometimes, even though you’re standing still, your connection to the website you’re trying to reach or the video you’re trying to stream just drops out. And sometimes, in densely populated areas, your carrier just can’t handle the demand, and kicks your connection to a slower speed. These are the mostly-inconsequential frustrations of which daily life is made.

But those, “ugh, again?” eye-rolling moments are a useful sort of barometer to show us what the data all says more clearly: 4G connections can be great, but in many areas they remain unreliable, and their speeds — and therefore, utility — are limited.

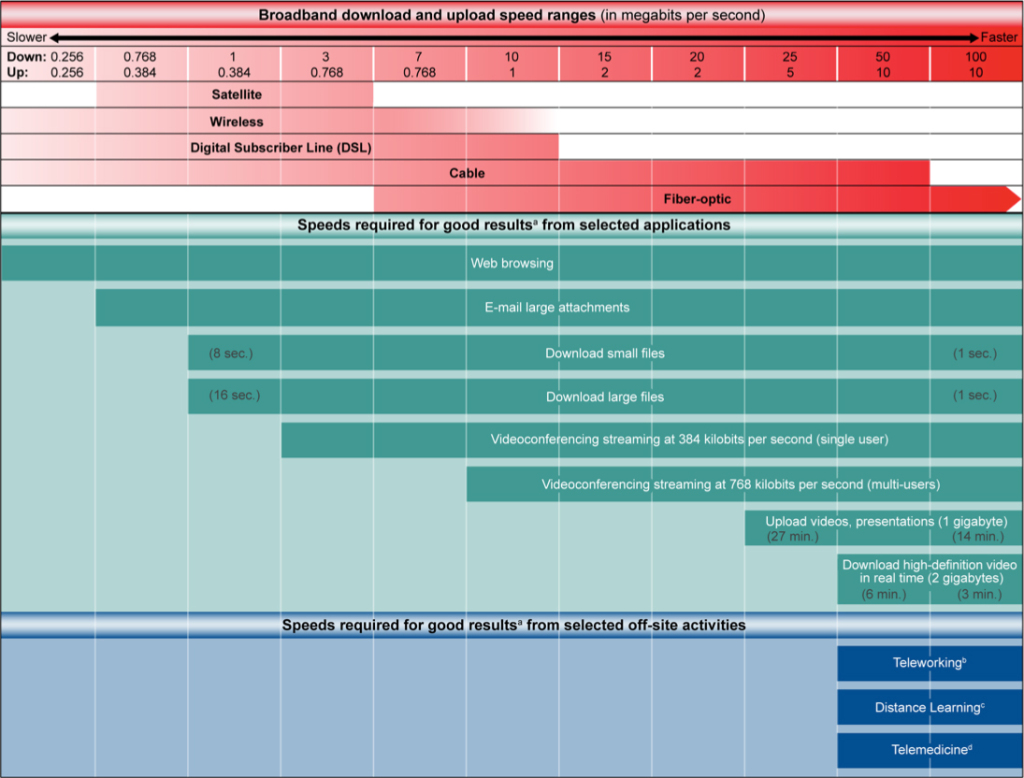

How limited? As part of a recent report looking at broadband connections in rural areas, the GAO put together a chart comparing the average network speeds of the common technologies — satellite, mobile, DSL, cable, and fiber — and stacked them up against the speeds required for most activities.

Average broadband technology speeds as compared to uses, via the GAO.

For wireless broadband, the results are mixed. The GAO considers the average wireless speed — between 1 and 10 MBps download — to be perfectly fine to use for basic web browsing and e-mailing. But for uploading files, streaming HD video, or taking part in any kind of real-time activity, mobile data doesn’t stack up. It takes cable or fiber for that.

The other half of that question of course is: can the average mobile data user actually expect to get the average mobile data speeds? And as you might expect, the answer is “it depends.”

Every year for the last four years, PC Mag runs an experiment and report looking at real-world mobile connectivity around the nation. Their 2013 “Fastest Mobile Networks” report tested not only the speed but also the consistency and reliability of major providers’ 4G mobile networks in 30 major metro areas and the rural/suburban stretches of interstate between them.

Their results for both the fastest connections and the most consistent ones ended up varying hugely both by carrier and by location. In some cities, with some carriers, they were able to record download speeds of over 65 Mbps — certainly sufficient for most tasks, and better than many home users reach on their wired connections.

But as the PC Mag folks explain, those are only maximum speeds. The standard needs to include reliability, as well: what’s the average network speed, as opposed to the maximum? And can the carrier sustain it?

The standard for a useful 4G LTE broadband connection download speed is considered to be a reliable 8 MBps, and all of the carriers that the reporter at PC Mag spoke with agreed that it was the level of service they aim for. If a carrier can offer a constant 8 Mbps or better connection most of the time then that carrier truly offers a viable mobile network.

That “most of the time,” though, turns out to be the big catch:

AT&T failed to deliver 8 megabits down at least 20 percent of the time in two thirds of our cities. Verizon did even worse; it only delivered 8Mbps results 80% of the time in Detroit and Indianapolis. And Sprint’s hometown of Kansas City was the only place where we saw Sprint LTE exceeding 8Mbps more than half the time.

The accompanying graph shows that even in the best-connected cities, 100% reliability is still a dream for the future.

And outside of those best-connected cities, the situation is far worse. The constant challenge of broadband expansion is that people who don’t live in urbanized areas pretty much never get to see the benefit. Expanding rural broadband is a major project at the FCC, and it’s work that’s still not done.

AND THEN THERE’S THE MONEY…

All those fancy high-tech 4G LTE mobile data plans? They’re expensive. Really expensive. Especially if you actually want to use your phone or tablet to do things with.

Pricing for data plans varies widely among the big four carriers, and their options — nested in piles of differently managed family plans, miscellaneous fees, overage charges, and phone rebates — can be difficult to compare in an apples-to-apples sense. Even so, they generally fall into a standard three-figure range.

Earlier this year, a research firm analyzed survey data from 2013 to see who was paying the most for their mobile phone plans. Verizon customers had the highest average monthly bill, coming in at $148. T-Mobile’s was lowest — but “most expensive” and “cheapest” were relative. Verizon’s $148 is not exactly astronomically above Sprint’s $144, AT&T’s $141, or even T-Mobile’s $120.

Although that $28 per month between the average Verizon bill and the average T-Mobile bill adds up to about $216 per year, that’s barely a drop in the metaphorical bucket as compared to how the average wireless data bill compares to the average home fixed broadband bill.

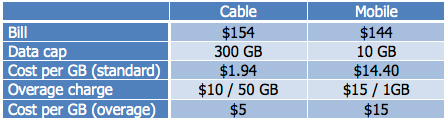

We did the back-of-the-envelope math when Comcast claimed 4G was viable competition to cable. And although the numbers are rough averages, the picture they paint remains clear: mobile data costs consumers about ten times as much per gigabyte used as standard broadband does.

We did the back-of-the-envelope math when Comcast claimed 4G was viable competition to cable. And although the numbers are rough averages, the picture they paint remains clear: mobile data costs consumers about ten times as much per gigabyte used as standard broadband does.

CAN’T IT BE DONE BETTER AND CHEAPER?

The problem isn’t the phone tech; it’s the carriers that own the infrastructure. Verizon is almost everywhere but has a slower network. AT&T has a faster network but isn’t available in as many areas. T-Mobile has better pricing but is both slower and harder to find. And Sprint is, well, still trying to figure out what on Earth to do next.

Mobile data prices are high in part because they can be, but also in part because of the basic rule of supply and demand. Demand isn’t dropping; it’s skyrocketing. And supply to match has been slower to catch up.

Increasing mobile network capacity requires two new things. The first is that basically, we need to build even more cell towers. But one of the guiding principles of business is that companies only want to spend money if it guarantees they can make more money. Rural and suburban LTE expansion faces some of the same challenges as rural and suburban cable or fiber expansion does: most companies don’t want to spend what the infrastructure buildout costs for as few potential customers are available in the area. And so an area remains underserved.

And on top of all that, increasing the reach of one provider is still only half the challenge. If Verizon ends up with a truly national, reliable, high-tech, high-speed mobile network that you can reach from any square foot in the continental United States, that would be amazing — and it would also be a monopoly in many areas, with all the trouble for consumers that creates. The biggest markets, like DC, New York, and L.A., will always have some competition around to keep carriers in line. But even though millions of folks live in or near big cities, millions more don’t. Prices would most certainly not drop, under those conditions, and customer service would probably take a tumble too.

As with any other major national project, then, getting a truly 21st century mobile data network built out nationwide will take a combination of private investments and government policies, at both the state and federal levels. Companies like Verizon and AT&T will require incentives — lucrative ones — to build where they otherwise wouldn’t.

MAKING (AIR)WAVES

Speaking of federal policy, that’s the other infrastructure challenge: available broadband spectrum. All this data goes over radio waves just like every other kind of transmission. Certain segments of the spectrum are allocated to mobile providers. The more of those segments that the cell phone companies have access to, the more traffic they can move through the ether simultaneously.

The question then, of course, is who controls the segments of the spectrum? If one company were to control something like 75% of the spectrum, there’d be no room left for new companies to try building out infrastructure, or to offer new products and services. In short, there’d be no way for anyone to compete.

It’s the FCC’s job to make sure that no one company controls too many of the available wavelengths, and to help make more available when the spectrum already in use is no longer enough. And that’s exactly what they’re doing: this fall, the FCC will hold a big spectrum auction to make more frequencies available to mobile companies. The section of spectrum coming up for sale is considered particularly valuable, as it has the kind of reach and strength that mobile companies need in a bandwidth-intensive mobile market. The rules for the auction aren’t finalized yet, but currently the plan is to reserve chunks of it for smaller carriers, directly preventing AT&T and Verizon from gobbling it all up for themselves.

Will more spectrum do the trick and make 4g LTE data cheaper for consumers? Not by itself, not yet. It is a step on the long road to seeing mobile data potentially become dominant, though.

By the time mobile data is as effective as wired, we’ll probably be a couple of tech generations ahead of 4G, anyway. But with as much easier (and cheaper) as it is to build more cell towers than it is to run fiber cables across the continent, it’s easy to see why a company like Verizon will try anything to hasten the mobile future.

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.