Why College Isn’t Always A Good Financial Investment

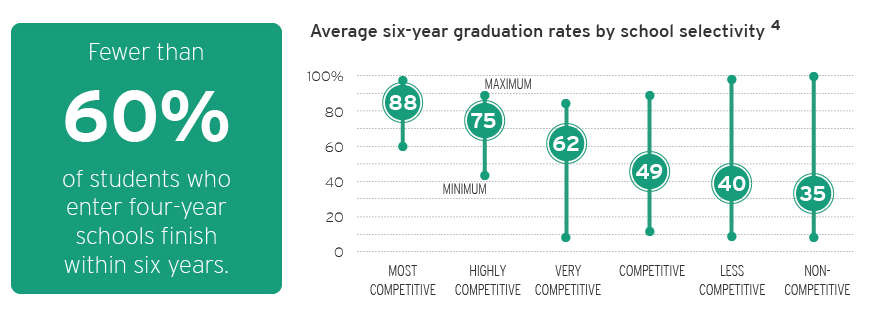

Given that fewer than 60% of college students obtain a degree in six years, some people may be throwing money away — and piling on student loan debt.

The report from the Brookings Institute highlights the numerous ways in which it is difficult to truly estimate the value of a college education.

For example, while college graduates from the most selective schools do tend to earn significantly more than those who choose to not acquire a further education, it could be argued that these people are inherently more motivated to succeed, regardless of education.

“If the smartest, most motivated people are both more likely to go to college and more likely to be financially successful, then the observed difference in earnings by years of education doesn’t measure the true effect of college,” reads the report.

It’s also difficult to obtain the actual price tag on an education. The report gives the example of Vassar College, which costs nearly $50,000/year in tuition and fees, but whose graduates tend to not earn very much compared to other highly competitive schools.

Yes, if the student is taking out student loans or paying cash for her Vassar education, then this is not exactly the best financial investment. But the Brookings paper points out that 60% of students in 2012 received an average of $30,000 in financial aid. Depending on how much of that aid is made up of grants and scholarships (as opposed to loans), the Vassar return on investment can go from as low as 6% to upwards of 9%, putting it in line with other schools.

Another thing to consider is the amount of time spent in college. Fewer than 60% of college students obtain a four-year degree within six years of starting. At schools rated “competitive” by Baron’s that rate is below 50%, while it sinks to 40% for “less competitive” schools and 35% for “non-competitive” colleges.

As we’ve written many times before, students at many of these non-competitive schools — especially the large number of for-profit colleges — also tend to take out the most student loans, and are more likely to default of these loans because of their inability to pay them back.

Meanwhile, the Brookings report figures that the average person who goes into the workforce straight out of high school earns more than $50,000 over those few years. So while a college graduate may leave school with a degree and a higher-paying job, the student loan burden may mean the graduate is worse-off financially than the person who chose to not seek a higher education.

The Brookings report does concede that there may be non-financial reasons for attending college that can’t be shown on a chart:

“[T]here are many non-monetary benefits of schooling which are harder to measure but no less important. Research suggests that additional education improves overall wellbeing by affecting things like job satisfaction, health, marriage, parenting, trust, and social interaction. Additionally, there are social benefits to education, such as reduced crime rates and higher political participation. We also do not want to dismiss personal preferences, and we acknowledge that many people derive value from their careers in ways that have nothing to do with money. While beyond the scope of this piece, we do want to point out that these noneconomic factors can change the cost-benefit calculus.”

Given the myriad complexities involved in determining whether or not a college education makes sense financially, the Brookings report does not provide guidelines for consumers, who will have to make their own pros/cons list and profit/loss projections before deciding whether to pursue that bachelor’s degree. However, the report does make some policy suggestions for lawmakers and regulators.

Much like the folks at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Brookings researchers believe that providing transparent, clear information to potential students is key. The Dept. of Education recently enacted a simple comparison-shopping form that allows applicants to get a better understanding of their financial aid packages, but it could go further. The report also suggests that there should be more, quality alternatives to the standard college education.

“It is a mistake to unilaterally tell young Americans that going to college — any college — is the best decision they can make,” write the researchers. “A bachelor’s degree is not a smart investment for every student in every circumstance.”

Want more consumer news? Visit our parent organization, Consumer Reports, for the latest on scams, recalls, and other consumer issues.